Boeing officials said Wednesday that the company is targeting Dec. 17 for the launch of the first unpiloted orbital test flight of the new Starliner crew capsule from Cape Canaveral on a week-long demonstration mission to the International Space Station, a precursor to a mission with astronauts next year.

Meanwhile, engineers in the New Mexico desert are readying a Starliner test vehicle for a pad abort test scheduled for the morning of Nov. 4, local time, during which the crew capsule will demonstrate its ability to escape an emergency on the launch pad, according to industry sources.

But officials did not say when the Starliner could be ready to launch with astronauts. The Starliner’s first crewed test flight will use a different spacecraft than the one set for launch in December.

NASA is counting on its commercial crew contractors — Boeing and SpaceX — to begin ferrying crews to and from the space station. The space agency’s final contracted seat to fly a U.S. astronaut to the station on a Russian Soyuz spacecraft launches in March 2020, and returns to Earth next October.

NASA has stretched the duration of astronaut stays on the space station this year to buy time for Boeing and SpaceX to finish building and testing their spacecraft. Space agency officials have also approved plans for Boeing’s first crewed test flight, originally slated to last a week or two, to extend as long as six months.

A similar agreement could be cinched with SpaceX soon.

And NASA may have to buy additional Soyuz seats from Russia, despite earlier statements from NASA officials that the unpopular purchases — which cost more than $80 million per seat at last report — were over.

John Mulholland, vice president and general manager of Boeing’s commercial crew program, said Wednesday that the company has set Dec. 17 as the target launch date for the Starliner’s Orbital Flight Test.

The mission will take off from Cape Canaveral on top of a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, dock with the space station two days later, then return to a parachute-assisted, airbag-cushioned landing at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico Dec. 24, assuming it launches on Dec. 17.

While the schedules could change — as they often do in the launch business — the new target dates mark the first time Boeing or NASA have provided an updated launch schedule for the Starliner program since April. The schedule for SpaceX’s commercial crew program has also not been officially updated in six months.

Josh Barrett, a Boeing spokesperson, said Wednesday that preparations for the pad abort at White Sands are going well.

“The crew and service modules are mated (for the pad abort),” Barrett said. “They’re fueling this week (and) should be going up on the test stand next week, and then preparing for final checkouts for launch.”

Read our earlier story for details on the Starliner pad abort.

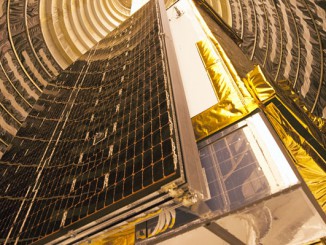

Technicians working inside Boeing’s Starliner factory at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida are installing ordnance on the crew module for the Orbital Flight Test this week, according to Barrett. He said teams will then install the heat shield and connect the crew module to the service module, fuel the spacecraft with hypergolic propellants, then transfer the vehicle to pad 41 for lifting atop its Atlas 5 launcher.

Stacking of the Atlas 5 rocket inside the Vertical Integration Facility at pad 41 should begin in the next few weeks. The Starliner spacecraft is expected to arrive at the launch pad some time in November.

An update on SpaceX’s commercial crew program could come Thursday, when NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine will tour SpaceX’s headquarters facility in Hawthorne, California.

Bridenstine and Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, will speak with reporters following the tour. NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, who are assigned to fly SpaceX’s Crew Dragon into orbit on the craft’s first piloted test flight, will join Bridenstine and Musk during the media availability Thursday.

SpaceX accomplished a pad abort test in 2015, and the company completed its unpiloted Crew Dragon test flight to the space station in March, but the company has run into difficulties since then with the ship’s abort system and parachutes.

Musk tweeted on Tuesday that the next major Crew Dragon test flight — an in-flight abort demonstration — could launch in late November or early December. During that test, a Crew Dragon capsule will ride a Falcon 9 booster into the sky over NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, then fire its SuperDraco escape engines to propel itself away from the rocket, mimicking a failure scenario on a real launch with astronauts on-board.

Before the in-flight abort, the Crew Dragon capsule will test-fire its SuperDraco thrusters on a test stand at Cape Canaveral in the coming weeks, repeating a test series that ended with the explosion of a Crew Dragon test vehicle in April. SpaceX determined that a faulty valve in the spacecraft’s propellant pressurization system caused the explosion, which occurred an instant before the capsule was supposed to fire its SuperDraco abort engines for a hold-down test.

Musk said SpaceX’s integration and test schedule suggests hardware for the Falcon 9 rocket and Crew Dragon spacecraft that will carry Behnken and Hurley into orbit could be at the Florida launch site, and ground testing could be completed, in about 10 weeks, or as soon as mid-December.

It’s not known how long NASA safety reviews might take to clear the Crew Dragon’s first flight with astronauts for launch, and Musk wrote on Twitter that parachute testing remains a major focus area for SpaceX’s crew program. He said SpaceX “had to reallocate some resources” to speed up the parachute development effort.

SpaceX has suffered multiple parachute failures, including an accident during a drop test in April over Nevada and a chute failure during the return of a Dragon cargo capsule from the space station in 2018. The Dragon cargo craft that experienced a chute failure was still able to successfully splash down in the Pacific Ocean slowed by its other parachutes.

Musk wrote he visited SpaceX’s parachute supplier, Airborne Systems, last weekend. Airborne and SpaceX are focusing on an “advanced” parachute design that “provides (the) highest safety factor for astronauts,” Musk tweeted.

SpaceX’s Crew Dragon uses two drogue parachutes and four main ring-sail chutes to slow its speed before splashdown at sea. The parachute system worked as designed during a splashdown in March to conclude an unpiloted Crew Dragon test flight to the station.

In an update last month, NASA said that SpaceX has completed 30 drop tests and 18 system-level tests on the Crew Dragon parachutes over the last four years.

“One of the most relevant benefits originating from the rigorous, multi-year parachute testing campaign is a better understanding of how to safely design and operate parachute clusters,” NASA said.

Other human-rated space capsules, such as the Starliner capsule and NASA’s Orion spacecraft, rely on three main parachutes. The cargo variant of SpaceX’s Dragon capsule also uses three main chutes.

But the Crew Dragon spacecraft is significantly heavier than the Dragon capsule currently in service, so SpaceX engineers designed the next-generation craft with four main parachutes similar to the ones flown on cargo missions.

“Specifically, NASA and SpaceX now have greater insight into what is termed ‘Asymmetry Factor,’ an integral part of how safety in design is measured and weighed. This asymmetry factor is an indicator of uneven load distribution between individual suspension lines attached to the parachute canopy,” NASA said.

“As a cluster of parachutes is deployed, the first parachute to open may crowd or bump others as they open up, causing an uneven load distribution on the main parachutes. If the lines or the joints are not designed to account for the unevenness or asymmetry, they might get damaged or even fail.

The April drop test was designed to simulate the Crew Dragon’s response to the loss of one of its four main parachutes. But an unexpected parachute failure occurred during the test, which provided engineers with a “unique insight into parachute loading and behavior,” NASA said.

“The test results have ultimately provided a better understanding of parachute reliability and caused a closer examination of the current industry standard used to calculate the asymmetry factor.”

NASA said SpaceX is using the new data to calculate structural margins and influence parachute design.

SpaceX has completed successful parachute tests since April, including a recent test to simulate the parachutes’ performance during a pad abort scenario.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.