STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

After 10 years, two successful test flights and a $6 billion investment in American enterprise, NASA is poised to launch four astronauts to the International Space Station this weekend, the first government-certified flight of a commercially developed SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft.

Originally expected to take off Saturday, the launch was delayed to Sunday, at 7:27 p.m. EST, because of expected high winds at the Kennedy Space Center and weather off-shore where the Falcon 9 rocket’s first stage will attempt to land on a SpaceX droneship. The company plans to re-use the booster for the next Crew Dragon flight.

Appropriately enough, the three-man one-woman crew named their spaceship “Resilience.”

“That means functioning well in times of stress or overcoming adverse events,” Crew-1 commander Mike Hopkins said during an earlier briefing. “I think all of us can agree that 2020 has certainly been a challenging year — global pandemic, economic hardships, civil unrest, isolation.

“And despite all of that, SpaceX, NASA has kept the production line open and finished this amazing vehicle that’s getting ready to go on its maiden flight to the International Space Station.”

Joining Hopkins aboard the SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule will be F/A-18 carrier pilot Victor Glover, research astronaut Shannon Walker and Japanese astronaut Soichi Noguchi.

It will be the second flight for both Hopkins and Walker, who flew earlier aboard Russian Soyuz spacecraft, and the third for Noguchi, a veteran of both the Soyuz and the space shuttle. Glover, the first African American to join a long-duration space station crew, is making his first space flight.

If all goes well, the Crew Dragon will execute an automated rendezvous with the International Space Station, gliding in for a docking at the lab’s forward port around 11 p.m. Monday to kick off a six-month stay.

Kennedy Space Center remains closed for normal business due to coronavirus protocols and the astronauts have been in strict quarantine for the past several weeks to make sure no one carries the virus to the space station.

Against that backdrop, SpaceX founder Elon Musk tweeted overnight that he “was tested for COVID four times today. Two tests came back negative, two came back positive.” He later added he had experienced “mild sniffles & cough & slight fever past few days. Right now, no symptoms.”

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told The Washington Post that contact tracing showed Musk had not come in contact with anyone who had access to the Crew-1 astronauts and no impact on the launch was expected.

NASA managers did not attempt to warn off possibly large crowds expected to gather along Florida’s “Space Coast” to witness the weekend launching. But Kathy Lueders, director of NASA’s space exploration directorate, urged the public to be cautious, to wear masks and socially distance wherever they might gather.

“We’re expecting a large turnout,” she said. “We do want folks to celebrate with us (but) we do want people to be careful when they’re out there. We’d be really sad if this was a super-spreader event.”

COVID aside, NASA and SpaceX managers held a launch readiness review Friday to assess the weather and the performance of the Falcon 9 rocket’s nine first stage engines during a test firing Wednesday. The engines received a clean bill of health and forecasters predicted a 60 percent chance of acceptable weather at the launch site Sunday.

Mission managers will continue to assess conditions in the Atlantic Ocean along the Crew Dragon’s northeasterly trajectory to make sure winds and sea states are acceptable in case of a malfunction that could force the crew to make an emergency splashdown.

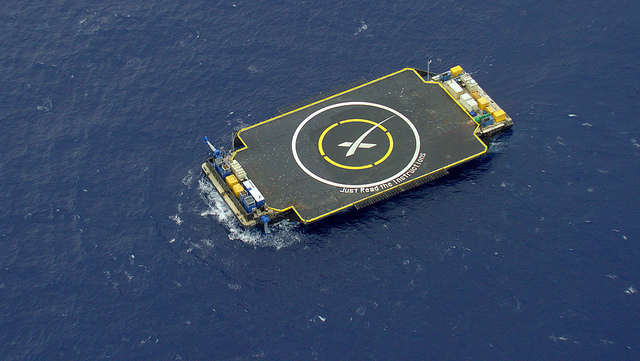

Relatively calm seas are required for recovery of the Falcon 9’s first stage. A company droneship, the “Just Read the Instructions,” went to sea Thursday, heading for the landing zone several hundred miles northeast of Cape Canaveral.

“Landing weather for the first stage is a big deal,” Lueders said Thursday. “It’s the stage we’ll be using for Crew-2, so we care about it. Not that we don’t care about them (all), but this is an important stage.”

NASA is counting on the Crew-1 flight and follow-on missions by SpaceX and Boeing to end the agency’s sole reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for trips to and from low-Earth orbit. NASA has spent $4 billion since 2006 buying seats aboard Soyuz spacecraft and another $6 billion to date working with SpaceX and Boeing to develop new commercial crew ships.

To achieve “operational” status, the agency had to “human rate” the SpaceX Crew Dragon and Falcon 9 rocket, an exhaustive process culminating in two test flights, one unpiloted and the other carrying astronauts Douglas Hurley and Robert Behnken to the space station for a 64-day stay earlier this summer.

With two successful test flights behind them, NASA engineers were able to certify the spacecraft after a detailed analysis of telemetry and inspections of the flight hardware. It was the first such certification since the space shuttle was being built in the 1970s and the first ever granted a commercially developed spacecraft.

“I believe 20 years from now, we’re going to look back at this time as a major turning point in our exploration and utilization of space,” said Phil McAlister, director of commercial spaceflight development at NASA Headquarters. “It’s not an exaggeration to state that with this milestone, NASA and SpaceX have changed the historical arc of human space transportation.

“Not only can NASA transport our astronauts to and from the International Space Station with U.S. systems, but now, for the first time in history, there is a commercial capability from a private sector entity to safely and reliably transport people to space.”

Thanks to multiple NASA contracts to deliver cargo and astronauts to the space station, “this is all leading up to the big operational cadence,” said Benji Reed, SpaceX director of crew mission management. “And this is super cool.”

“Once we start with Crew-1, we’ll be moving into a cadence where over the next 14 months, we will need to fly seven Dragon missions,” he said. “There will be a number of crewed missions, Crew-1, Crew-2, Crew-3 and ongoing. … At the same time, we’ll be flying four cargo flights onto station. So this really is a new era for for us as a company and also for commercial space in general.”

NASA managers opted to press ahead with the Crew-1 flight after work to correct a handful of problems in the wake of this summer’s Demo-2 test flight. In one case, SpaceX beefed up the heat-shield insulation in areas where more re-entry erosion was seen than expected. In another, the company improved a system used to trigger release of stabilizing drogue parachutes during descent to splashdown.

More recently, SpaceX had to resolve a subtle Falcon 9 engine problem that triggered a launch abort Oct. 2 that grounded a U.S. Space Force navigation satellite. The problem was traced to residual contamination in turbopump machinery found in the GPS rocket. Similar problems were found in the Crew-1’s Falcon 9.

Two engines in each booster were replaced and the GPS satellite was successfully launched Nov. 5. SpaceX test fired the engines in the Crew-1 Falcon 9’s first stage on Wednesday and no problems were seen.

Standing by to welcome the Crew-1 astronauts aboard the station will be Expedition 64 commander Sergey Ryzhikov, Sergei Kud-Sverchkov and NASA astronaut Kate Rubins. Rubins used NASA’s last currently contracted Soyuz seat when she and her two crewmates blasted off Oct. 14 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome aboard the Soyuz MS-17/63S spacecraft.

With the arrival of the Crew Dragon, the station crew will swell to seven, with five working and living in the U.S. segment of the lab while Ryzhikov and Kud-Sverchkov operate systems in the Russian segment.

“It’s going to be great to watch the Crew-1 crew come through that hatch, and we’ll definitely welcome them on board because with more crew members, we can spend a lot more time doing scientific research and experiments,” Rubins said before launch.

“There’s a certain amount of time we have to devote just to station maintenance, and with only one or two U.S. and international partner crew members, it’s hard to get all of the science done that we want to do. So having all these extra crew members there means we can accomplish that much more scientifically.”

The station’s life support systems, including its water recycling equipment and carbon dioxide removal gear, have been beefed up to support a seven-member crew and additional stores and supplies have been laid in.

But the U.S. segment of the station only has four crew “sleep stations” and Hopkins plans to bunk with a sleeping bag in the powered-down Crew Dragon. A new crew compartment is expected to launch next year.

If all goes well, Hopkins, Glover, Walker and Noguchi will spend 165 days aboard the space station, welcoming four cargo ships along the way. Multiple spacewalks are planned to outfit an external experiment platform on the European Space Agency’s Columbus science module and to upgrade the station’s solar power system.

And throughout their stay, the crew will focus on a wide variety of experiments and research projects.

The next Crew Dragon, carrying Crew-2 astronauts Shane Kimbrough, Megan McArthur, Japan’s Akihiko Hoshide and European Space Agency astronaut Thomas Pesquet, is scheduled for launch around March 30. Three Russians — Oleg Novitsky, Pyotr Dubrov and Sergey Korsakov — will arrive aboard a Soyuz on April 10, briefly boosting the station crew to 11.

Ryzhikov, Kud-Sverchkov and Rubins return to Earth one week later, on April 17, with a landing on the steppe of Kazakhstan. Hopkins and his Crew-1 colleagues will follow suit around May 1, splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean northeast of Cape Canaveral or in the Gulf of Mexico south of Pensacola, depending on the weather.

That will leave Kimbrough and his Crew-2 colleagues on board the station along with Novitsky, Dubrov and Korsakov until the next Crew Dragon arrives in the fall.

“We’re considering seven crew is pretty much our steady state going forward,” said Kenny Todd, NASA’s space station integration manager. “You might have periods where you’ll have a couple of vehicles and a larger crew during some handover periods. But the steady state crew size will be seven.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.