Lockheed Martin’s launch services team hopes to lure up to four commercial customers per year to fly on United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 booster as a stream of U.S. government missions is forecast to dry up starting in 2017, according to Lockheed Martin’s rocket sales chief.

For the Atlas 5 marketing team, it represents a significant change after being mired on the sidelines of the multibillion-dollar global launch services market for a half-decade. The first fully commercial Atlas 5 launch from Cape Canaveral in nearly five years took off Oct. 2 with Mexico’s Morelos 3 communications station.

“I go after customers aggressively all the time,” said Steve Skladanek, president of Lockheed Martin Commercial Launch Services, in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “There are a couple of customers who have expressed a desire to launch in late 2016. We’re looking for ways to create a new opportunity toward the end of 2016, working very closely with ULA to create that capability.”

Two issues commonly raised by commercial operators with United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 rocket are its cost and schedule availability — having an opening when a customer wants it.

Asked if that landscape is changing for Atlas 5, Skladanek said: “I can say emphatically yes on both fronts.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Steve Skladanek. Become a member today and support our coverage.

A block buy of 36 rocket cores by the U.S. military in December 2013 brought down the unit cost of Atlas 5 rockets, Skladanek said. He did not disclose the going price of a commercial Atlas 5 mission — ULA officials last year said the block buy brought the basic “401” Atlas 5 configuration to as little as $100 million for commercial flights — but Skladanek stressed the Atlas 5’s reliability and mission assurance as strengths adding to the launcher’s value in the global market.

The U.S. military’s flagship satellite communications networks — the Air Force’s nuclear-hardened Advanced EHF platforms and the Navy’s MUOS satellites tailored to link forces on the move — will soon be completed. There may also be fewer launches of GPS navigation satellites by ULA.

“Starting in 2017 and on out, we’re seeing less of a government demand on the Atlas vehicle, which obviously is going to open up more opportunities for commercial options,” Skladanek said. “I’ve been marketing those, and customers are very enthused with the availability on our manifest starting in 2017.”

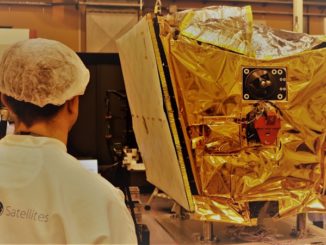

Lockheed Martin announced a launch contract with EchoStar Corp. in August to deliver the EchoStar 19/Jupiter 2 Ka-band broadband communications satellite to orbit in November 2016.

The launch deal went to Atlas 5 after production delays meant the satellite would not launch until the second half of 2016, when Arianespace’s Ariane 5 rocket had no slots to accommodate a large spacecraft like EchoStar 19/Jupiter 2, which is being built by Space Systems/Loral.

The satellite was originally contracted to launch on Ariane 5, but Arianespace officials said they worked with EchoStar to secure a place in the Atlas 5’s manifest in late 2016.

The Ariane 5 typically hauls up two large telecom satellites per mission, and pairing a larger craft with a smaller craft to fit within the rocket’s lift envelope is sometimes a challenge.

The EchoStar 19/Jupiter 2 agreement puts the Lockheed Martin’s Atlas 5 backlog at two flights. Commercial cargo and crew missions to the International Space Station fall in ULA’s order book because the end customer is NASA.

Lockheed Martin is responsible for marketing the Atlas 5 to commercial customers, while ULA handles sales to the U.S. government. For commercial flights, ULA still is in charge of construction of the rocket and launch operations.

ULA has 17 missions on its manifest in 2016, according to Tory Bruno, the company’s chief executive. Twelve of the launches are Atlas 5s, plus four Delta 4s and one Delta 2.

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of a recent media roundtable with Tory Bruno. Become a member today and support our coverage.

No more than nine Atlas 5s have ever flown in a calendar year before, and Skladanek did not say whether the opening for a commercial flight in late 2016 would add to ULA’s 17-mission total or replace a government launch already in the queue.

“They’ve worked to identify how they could do that,” Skladanek said. “They’ve shown it to me. It is a possibility, and now it’s simply a matter of working with the customer to see if it’s going to work out for them.”

Attracting commercial customers is vital to maintaining the Atlas 5’s supercharged launch rate — the rocket is in the midst of three launches in 28 days — but Bruno says the commercial market is not sufficient to erase the company’s reservations about a U.S. law that restricts the use of the Atlas 5’s Russian RD-180 main engine in future military launch contracts.

The debate centers on a clause in the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act that limits ULA’s use of Russian RD-180 engines on the Atlas 5 booster stage for U.S. national security space missions, and calls for the complete phaseout of the RD-180 for military launches by 2019. The law says no RD-180 engine paid for after Feb. 1, 2014, when the U.S. government says Russia’s incursion into Crimea began, can be applied toward future launch competitions with SpaceX, which is now certified to fly the Defense Department’s most critical satellite payloads.

The legislation exempts engines slated for launches under the 2013 block buy, plus five more RD-180s. But ULA says it has already committed those five powerplants to other Atlas 5 missions for NASA and commercial customers. An updated defense authorization bill passed by Congress earlier this month gives ULA access to four more engines for military missions, but President Barack Obama has said he will veto the legislation over a disagreement with congressional spending arrangements.

Bruno has threatened to not bid on defense launch contracts until more engines are made available to ULA, and commercial contract wins alone are not enough to build up the Atlas 5’s manifest in coming years to keep the rocket viable, he said.

“This is not enough engines,” Bruno told reporters Oct. 2. “We’re going to need more. We need at least 14, and this provided us four,” assuming President Obama signs the bill into law.

ULA ordered 29 engines from Russia’s NPO Energomash before the 2014 ban, and 15 of the RD-180s will go toward ULA’s block buy commitment, leaving 14 engines purchased and unusable for military launch bids, according to the company.

Bruno said the five engines tied to commercial and civil Atlas 5 launches cannot be re-applied to military missions, and he called for Congress to permit ULA to bid with all 14 engines it had ordered but not paid for before the outbreak of the conflict in Crimea.

He said ULA never made its annual RD-180 engine order from Russian engine-maker NPO Energomash — through the U.S.-based intermediary RD AMROSS — as scheduled earlier this year.

“Because of the uncertainty last year created by the NDAA, we did not purchase RD-180s when we normally would have at the end of the year,” Bruno said. “We have been working our way down through that reserve ever since. We will be in a position of having difficulty managing the flow in the factory very soon.”

Without relief on the RD-180 engine front, or a national security waiver signed by Defense Secretary Ashton Carter, ULA will not submit bids on launch competitions with SpaceX, beginning with a procurement for launch of a GPS navigation satellite in 2018.

Proposals for that competition are due Nov. 16.

SpaceX founder and chief executive Elon Musk sent a letter to Defense Secretary Carter on Oct. 5, calling ULA’s threat to sit out the GPS 3 launch competition “nothing less than deceptive brinkmanship for the sole purpose of thwarting the will of Congress,” according to a report by Reuters.

Musk called for Carter to not approve a waiver to allow ULA to continue using RD-180s beyond what is spelled out in last year’s defense authorization law.

Bruno said ULA could not justify the expenditure of a fresh engine purchase from Russia without assurances it would have customers to use them. The RD-180 ban does not apply to commercial or NASA launches using the Atlas 5, but even contract wins in those markets are not enough to justify a fresh engine order, according to Bruno.

“In the next several years, the national security space missions continue to be the core of our business — the core market — until they begin to trail down a few years from now,” Bruno said. “With an outright ban on the RD-180, which essentially bans the Atlas from the marketplace, this put a lot of risk and uncertainty into what the future will hold when we purchase long-lead materials like engines. Unlike other defense contractors, we largely fund that ourselves. They have to be ordered in large batches from the Russians, so it is a considerable financial outlay.”

Bruno said ULA has been more successful than he expected at securing commercial launch deals in the last year. Two upcoming launches of Orbital ATK’s commercial Cygnus space station resupply freighter that are now in Atlas 5’s near-term manifest — those flights were booked directly with ULA — and the EchoStar 19/Jupiter 2 contract win were not on ULA or Lockheed’s radar a year ago.

A look at the Atlas 5’s projected manifest later this decade shows openings for two to four commercial satellite flights per year, according to Skladanek. The rest of the Atlas 5’s flights will carry up military satellites, NASA science missions, and astronaut crews to the space station with Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner capsule.

On the commercial market, Atlas 5 stacks up against the Ariane 5 rocket and SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy boosters, which together have snatched the lion’s share of competed commercial launch contracts in recent years. Russia’s Proton rocket, marketed by International Launch Services, is also a major player.

“As far as the cost goes, it is probably the worst kept industry secret that Atlas is a pricey vehicle,” Skladanek said. “We contend that it’s certainly worth it because of its track record and because of its date certainty, and in fact, work with customers to show them how it’s more about value of the launch service, and the value is so much more than just the price … They understand that. That said, we’re still working with ULA to find ways to bring the overall cost down, and we’re finding some success there.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.