After years of anticipation, SpaceX launched the first test flight of its full-scale Starship rocket Thursday from South Texas, but the mission ended four minutes later as the vehicle veered out of control and self-destructed over the Gulf of Mexico following multiple engine failures.

The Starship rocket lifted off from Starbase, SpaceX’s privately-owned launch site east of Brownsville, Texas, at 8:33 a.m. CDT (9:33 a.m. EDT; 1333 UTC) Thursday. The liftoff began what was — in a best-case scenario — expected to be a 90-minute around-the-world test flight culminating in a splashdown of the rocket’s upper stage in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii.

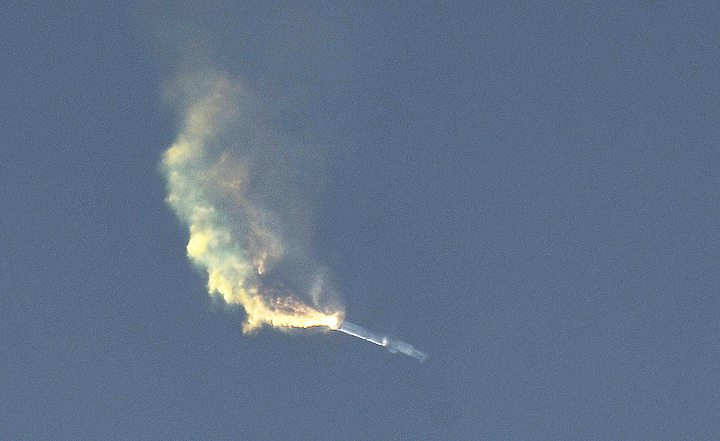

But at least six of the 33 methane-fueled Raptor engines on the Super Heavy booster, or the rocket’s first stage, shut down as it climbed into the sky. The Starship lost control around two minutes into the mission, veering from its planned flight corridor until an autonomous fight termination system blew up the rocket four minutes after liftoff. There were no people or operational payloads on-board the rocket.

Flight data displayed on SpaceX’s live webcast indicated the rocket reached a maximum altitude of 24 miles (39 kilometers) and a top speed of 1,340 mph (2,157 kilometers per hour). The test flight reached supersonic speed and continued beyond the point of maximum aerodynamic pressure, when the vehicle had to endure the harshest structural loads of its ascent.

Debris from the rocket fell into the Gulf of Mexico after the explosion.

Despite the early end to the demonstration mission, SpaceX said engineers will apply lessons learned from the launch to future Starship test flights. The result wasn’t a big surprise, with SpaceX careful to set low expectations leading up to the launch.

In a statement Thursday afternoon, SpaceX said the Starship’s Super Heavy booster stage “experienced multiple engines out during the flight test, lost altitude, and began to tumble.”

“With a test like this, success comes from what we learn, and we learned a tremendous amount about the vehicle and ground systems today that will help us improve on future flights of Starship,” SpaceX said.

Liftoff from Starbase pic.twitter.com/rgpc2XO7Z9

— SpaceX (@SpaceX) April 20, 2023

Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, first unveiled plans for the launch vehicle that would become the Starship in 2016. Since then, SpaceX has refined its design, selecting stainless steel for its primary structure and rapidly building a factory and launch pad on the Texas Gulf Coast.

The new rocket, which SpaceX intends to eventually make fully reusable, is designed to ferry up to 150 tons of cargo into low Earth orbit. Missions to destinations beyond, like the moon, will require SpaceX to master in-orbit refueling, which has never been attempted at such large scales.

The Starship launch vehicle is staggering in size, standing some 394 feet (120 meters) tall with a diameter of 30 feet (9 meters), wider than the fuselage of a 747 jumbo jet and larger than any rocket ever built. The rocket weighed about 11 million pounds fully loaded with methane and liquid oxygen.

With all 33 engines firing, the rocket would have generated 16.7 million pounds of thrust, draining more than 40,000 pounds (about 20 metric tons) of propellant from its tanks every second. However, three Raptor engines appeared to fail at liftoff Thursday, so the 30 remaining engines on the Super Heavy booster likely produced around 15 million pounds of thrust, assuming they were all at full power. At least three more Raptor engines shut down in flight before the rocket started tumbling.

Elon Musk tweeted that engineers “learned a lot” from the test flight. He added that the next Starship launch could happen in a few months. SpaceX is finishing up work on the next Super Heavy booster and Starship vehicle in Texas.

But repairs and redesign of the Starship launch pad could throw a wrench into those plans. The blast from the Starship’s engines sent a shower of debris across the launch site, damaging tanks and other equipment. The launch of the world’s largest rocket also left a large crater in the concrete under the circular launch mount.

SpaceX did not build the launch pad at Starbase with a flame trench or flame diverter, design features common to other heavy-lift launch pads. Those structures are designed to direct the blast energy and hot engine exhaust away from sensitive equipment around the launch site, reducing the risk of damage.

There was also no water deluge system at the launch pad for the test flight Thursday. Other launch pads, including SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launch facilities in Florida and California, use water to dampen acoustic energy during liftoff.

Damage to the launch pad at SpaceX’s Starbase complex was high on the list of concerns Musk had before the Starship test flight.

“I guess I’d like to just set expectations low,” Musk said Sunday in a Twitter Spaces meeting with his subscribers. “If we get far enough away from the launch pad before something goes wrong, I would consider that to be a success. Just don’t blow up the launch pad.”

SpaceX scrubbed the first launch attempt for the Starship test flight Monday due to a frozen valve in the pressurization system on the Super Heavy booster. Technicians were seen working around the base of the rocket between the launch attempts, and more than 100 tanker trucks delivered fresh liquid nitrogen, liquid oxygen, and methane to the launch pad’s storage tanks ahead of the second Starship countdown Thursday.

The Super Heavy booster surpassed total power generated by the Soviet Union’s N1 launch vehicle, which had 30 engines with 10 million pounds of thrust. The N1 never reached space on any of its four test flights from Kazakhstan between 1969 and 1972. The Starship test flight Thursday made it further on the climb to space than any of the N1 rockets more than 50 years ago.

SpaceX’s giant new rocket also produced about twice the thrust of NASA’s Saturn 5 moon rocket from the Apollo program, or NASA’s Space Launch System rocket that successfully flew for the first time in November on a test flight for NASA’s Artemis lunar program.

If Thursday’s test flight reached its full duration, the Starship vehicle — effectively the upper stage of the rocket — would have detached from its Super Heavy booster about three minutes into the mission, then lit its six Raptor engines to accelerate to a velocity just shy of the speed required to reach a stable orbit around Earth.

The Starship, numbered Ship 24 in SpaceX’s nomenclature, would have coasted through space for more than an hour, reaching a peak altitude of about 146 miles (235 kilometers) before re-entering the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean, and finally making a high-speed impact north of Hawaii. The vehicle was covered in thousands of ceramic tiles to protect its stainless steel structure from the blistering heat of re-entry.

But the test flight Thursday did not get far enough to test the Starship upper stage, or its ability to re-enter the atmosphere. The Super Heavy booster was also programmed to reignite some of its Raptor engines after separating from the Starship upper stage, with a pair of maneuvers to guide itself back to a controlled splashdown in the Gulf of Mexico, a test for future landings to recover and reuse the booster. That objective was also not achieved Thursday.

“It may take us a few kicks of the can here before we reach orbit, and then beyond reaching orbit, we’ve got to bring the booster back and land,” Musk said. “We’ve got to bring the ship back and land. And in order for the reusability to be rapid, it’s got to land where it took off because transporting this gigantic beast around is extremely difficult.”

Musk said he thinks SpaceX can have the Super Heavy and Starship rockets recoverable and rapidly reusable in two or three years. The company wants to eventually retire its workhorse Falcon rocket family and Dragon spacecraft in favor of Super Heavy and Starship, although Falcon and Dragon are expected to remain in service launching crews and cargo the space station until the late 2020s.

“This is really kind of the sort of first step in a very long journey that will require many, many flights,” Musk said Monday. “For those that have followed the history of Falcon 9, and Falcon 1 actually, and our attempts at reusability, I think it might have been close to 20 attempts before we actually recovered a stage. And then it took many more flights before we had reusability that was meaningful, where we didn’t have to rebuild the whole rocket.”

Musk said SpaceX retrofitted the first flight-ready Super Heavy booster, called Booster 7, with shielding to protect its 33 Raptor powerplants from failures of nearby engines, a measure intended to reduce the chance of a cascading series of failures affecting multiple Raptor engines.

“This is very important because if you have 33 engines and if any one of them goes wrong, it’s like having a box of grenades, really big grenades,” Musk said.

It wasn’t immediately clear how many, if any, of the engine failures on the Super Heavy booster Thursday were the result of damage from problems on adjacent engines.

Once the rocket is proven, SpaceX wants to use the Starship vehicle to deploy the company’s Starlink internet satellites, flying heavier, next-generation versions of the broadband relay stations than the spacecraft now being launched by the smaller Falcon 9 rocket. An animation released from SpaceX showed the company’s concept for deploying Starlink satellites from a Starship vehicle in orbit, using a mechanism that works like a giant Pez dispenser.

SpaceX has also won a $2.9 billion contract with NASA to develop the Starship into a human-rated lander for the agency’s Artemis moon missions. A moon derivative of the Starship, assisted by Starship refueling tankers, will be utilized for a lunar landing with astronauts, an event NASA says could happen no earlier than 2025. SpaceX also has a deal with Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa to send a team of private citizens around the moon on a Starship flight.

Testing of the Starship’s in-orbit refueling technology, which is required for lunar sorties, will have to wait until the company can reliably launch the rocket into space, raising doubts among many observers, including NASA’s own inspector general, that the SpaceX-built moon lander can be ready before the end of 2025.

“Congrats to SpaceX on Starship’s first integrated flight test!” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson in a statement after Thursday’s launch. “Every great achievement throughout history has demanded some level of calculated risk, because with great risk comes great reward. Looking forward to all that SpaceX learns, to the next flight test — and beyond.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.