NASA managers tried for the last time earlier this month to coax the InSight lander’s long-stuck subsurface heat probe into the Martian soil, but after seeing no more progress, ground teams decided to end their efforts and focus on the mission’s other science objectives.

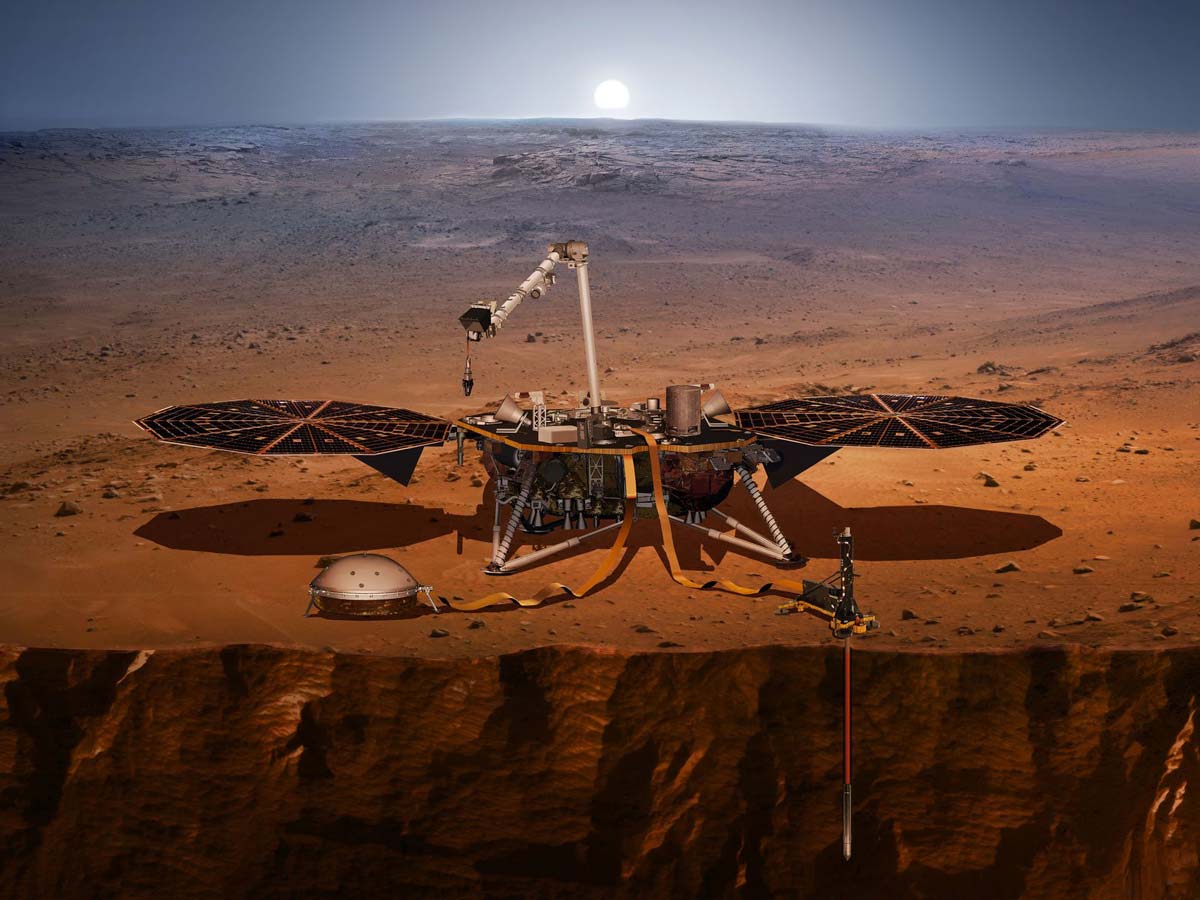

The German-built heat probe instrument is one of the $1 billion InSight mission’s three top scientific investigations, along with seismic sensors to detect “marsquakes” and an experiment to measure the wobble of the Red Planet’s rotation.

Together, the investigations were designed to help scientists learn about the deep interior of Mars, with an emphasis on studying the planet’s internal structure and composition, Martian tectonics, and meteorite impacts. The information will help researchers better understand how the rocky planets, like Earth and Mars, formed and evolved over the 4.5 billion-year history of the solar system.

While the other experiments continue producing results, an underground probe that is part of the InSight lander’s German-developed Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package, or HP3, instrument ran into trouble hammering itself into the Martian soil in the months after arrival on the Red Planet.

The stationary InSight lander touched down on Mars on Nov. 26, 2018, and ground teams sent commands for the HP3 instrument’s heat probe to start burrowing into the soil Feb. 28, 2019. It was the first time a mission tried digging so deep into the Martian surface.

Repeated tries at getting the self-hammering 16-inch (40-centimeter) probe into the soil, including attempts using the scoop on the lander’s robotic arm to help push the mole into the ground, have turned up empty.

“We’ve given it everything we’ve got, but Mars and our heroic mole remain incompatible,” said HP3’s principal investigator, Tilman Spohn of DLR, the German Aerospace Center, which developed the instrument.. “Fortunately, we’ve learned a lot that will benefit future missions that attempt to dig into the subsurface.”

The metal spike has embedded temperature sensors designed to measure the thermal gradient in the uppermost layers of the Martian crust. The mole has a trailing umbilical tether that was supposed to feed the science data back to the InSight lander for transmission to Earth.

But the probe needed to reach a depth of at least 10 feet, or 3 meters, to provide the expected science data. Instead, the mole only reached about a foot, or 30 centimeters, below the surface before its progress stalled.

After months of analysis by ground teams, managers approved a plan to use InSight’s robotic arm to remove a support structure housing to reveal the top of the mole for inspection by the lander cameras. The camera views revealed a pit had formed around the circumference of the mole, suggesting the Martian soil was not providing enough friction, or resistance, as the self-hammering probe attempted to drive itself into the ground.

Controllers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory then tried using the robotic arm’s scoop to press against the mole in a bid to apply extra pressure to compensate for the soil at InSight’s landing site, which appeared to clump together rather than loosely fall around the mole as it hammered.

After getting the top of the mole about an inch, or 2 to 3 centimeters, under the surface, teams at JPL tried a final time earlier this month to use the robot arm’s scoop to tamp down on the spike to provide added friction, NASA said.

“After the probe conducted 500 additional hammer strokes on Saturday, Jan. 9, with no progress, the team called an end to their efforts,” NASA said in a statement.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA said scientists and engineers learned much about Martian soil properties during their troubleshooting of the mole. The soil at the InSight landing site — on a broad plain named Elysium Planitia — has different characteristics than material observed at regions explored by other Mars missions.

“The mole is a device with no heritage. What we attempted to do – to dig so deep with a device so small – is unprecedented,” said Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer at JPL who has led efforts to get the mole deeper into the Martian crust. “Having had the opportunity to take this all the way to the end is the greatest reward.”

NASA approved a two-year extension for the InSight mission earlier this month.

InSight will continue measuring seismic tremors on the Mars, producing data to help scientists unravel the internal structure of the Red Planet. The solar-powered Mars lander will also continue operating a weather station, and ground teams will develop plans to bury a tether leading to InSight’s seismometer in hopes of eliminating noise in the data from the instrument.

The seismometer has recorded more than 480 marsquakes so far. Before InSight, scientists had not confirmed a detection of a seismic tremor on the Red Planet.

Lessons learned about using the lander’s robotic arm will help engineers devise a plan for burying the tether, according to NASA.

“We are so proud of our team who worked hard to get InSight’s mole deeper into the planet. It was amazing to see them troubleshoot from millions of miles away,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for science at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, in a statement. “This is why we take risks at NASA – we have to push the limits of technology to learn what works and what doesn’t. In that sense, we’ve been successful: We’ve learned a lot that will benefit future missions to Mars and elsewhere, and we thank our German partners from DLR for providing this instrument and for their collaboration.”

In 2019, Zurbuchen said the mole is not required for the InSight mission to achieve its minimum criteria for success.

The heat flow measurements intended to be collected by the HP3 instrument are part of InSight’s so-called “Level 1” requirements, but were listed as a stretch goal, or a “nice to have” objective, not as a threshold requirement for minimum mission success, said Bruce Banerdt, the mission’s principal investigator at JPL, in 2019.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.