The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft — assembled in Britain and set for liftoff in February — has completed environmental testing in Germany and is scheduled to ride a cargo plane to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida to begin launch preparations Oct. 31, several weeks earlier than planned to avoid complications stemming from Brexit.

The robotic solar probe will be packaged inside a pristine shipping container for the trans-Atlantic flight from Germany to the Shuttle Landing Facility runway at Kennedy. Ground teams will then transport the spacecraft to the Astrotech processing facility in Titusville for final functional tests, fueling and encapsulation inside the payload shroud of a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

The mission is jointly managed and funded by ESA, individual European member states, and NASA, with the U.S. space agency responsible for providing a launch for Solar Orbiter.

Liftoff of the Atlas 5 with Solar Orbiter from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 41 launch pad is scheduled during a two-hour window opening at 11:27 p.m. EST on Feb. 5 (0427 GMT on Feb. 6), according to Tim Dunn, the NASA launch director for the mission.

Airbus Defense and Space built the Solar Orbiter spacecraft at the company’s facility in Stevenage, England, north of London. The spacecraft departed the Airbus factory last year to begin a year-long test series at IABG in Ottobrunn, Germany, near Munich.

Solar Orbiter recently finished testing in Germany, and engineers confirmed the spacecraft can withstand the vibrations of launch and the extreme environmental conditions of space.

Günther Hasinger, the director of science programs at ESA, said mission managers decided to ship the spacecraft from its test site in Germany to the United States before the United Kingdom’s current date to leave the European Union on Oct. 31.

“There was a worry at some point, if a hard Brexit were to happen on the 31st of October, this could actually cause some severe disturbances in terms of customs,” Hasinger said. “It was a kind of risk mitigation assessment. We said let’s ship as early as possible just to avoid any turbulence.”

Although the spacecraft is currently in Germany, much of the hardware on Solar Orbiter originated in Britain, which raises export concerns related to Brexit, officials said. The date for Brexit, and whether Britain will leave the EU with or without a withdrawal agreement, remained unclear as of Tuesday.

The United Kingdom will remain a member state of ESA.

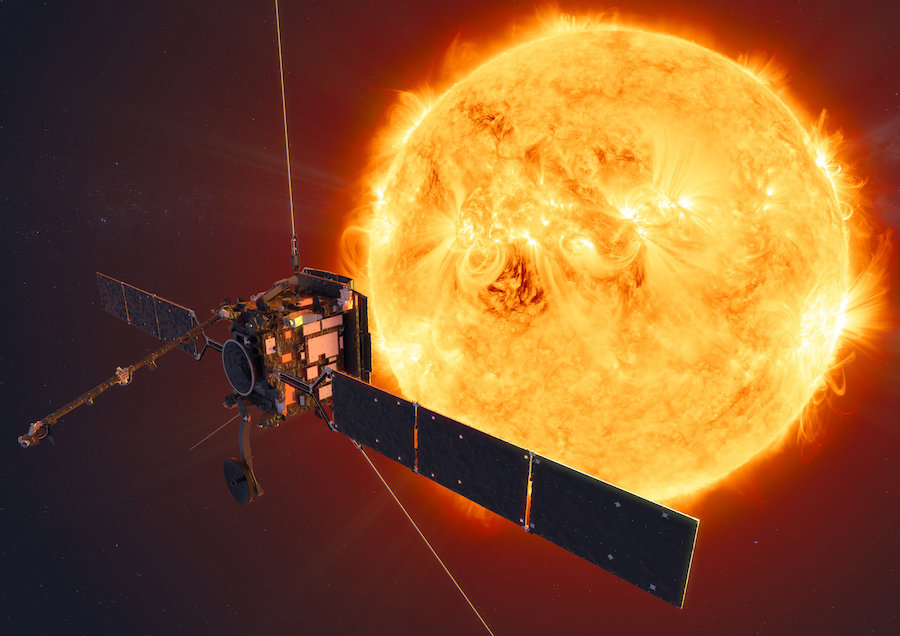

After launch, Solar Orbiter, or SolO, will use use gravitational assist flybys with Earth and Venus, placing the spacecraft in an orbit inside that of Mercury in 2022. Working in tandem with NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, Solar Orbiter will provide scientists will detailed measurements of the solar wind, and search for the drivers behind massive eruptions like solar flares.

“Solar Orbiter is clearly a new class in its own,” Hasinger said. “It has loads of instruments, which will go not as close as Parker Solar Probe, but quite close. Solar Orbiter will also have eyes. Parker Solar Probe can only sense and measure the plasma and the magnetic field, but Solar Orbiter also has six instruments that can really look at the sun, which is quite a challenge when you think it is reaching an environment where it’s about 600 degrees Celsius (1,100 degrees Fahrenheit). It’s like being in a pizza oven, so you have to make sure that you don’t burn the instruments.”

Parker Solar Probe, launched last year, faces much hotter conditions, where scorching temperatures would melt any camera exposed to the sun.

The planetary flybys will also use gravity to nudge Solar Orbiter into an inclined orbit around the sun, outside of the plane of the planets.

“One additional interesting element that has never been done before is that Solar Orbiter will be able to image the poles of the sun,” Hasinger said. “There are still mysteries around our understanding of the energy sources in the sun that produces the magnetic field and solar flares. A lot of people now think that some of the mysteries are actually hidden in the poles, which we have never seen.”

Scientists say the polar regions may also play a role in regulating the sun’s 11-year cycle.

ESA funded more than half of Solar Orbiter’s budget, and development of the mission took a few years longer than anticipated. When ESA approved the mission in 2011, Solar Orbiter was planned for launch in 2017.

The rest of the funding came from NASA and European member states, which paid for Solar Orbiter’s launch and scientific instruments.

“If you add up everything, it ends up in the 1.4 to 1.5 billion euro ($1.5 billion to $1.7 billion) range,” Hasinger said.

Before Solar Orbiter’s launch in February, ULA plans another Atlas 5 launch set for Dec. 17 carrying Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule into Earth orbit on its first unpiloted test flight to the International Space Station. The Orbital Flight Test mission, under contract to NASA, is a prerequisite for astronaut flights on the Starliner spacecraft next year.

After another round of delays, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said this month that the commercial crew program is the agency’s highest priority. Until new crew capsules from Boeing and SpaceX begin flying, NASA must rely on Russian Soyuz spacecraft to ferry astronauts to and from the space station.

In an interview last week, Dunn said launching the Starliner capsule Dec. 17 and then Solar Orbiter on Feb. 5 would be a “pretty quick turnaround” for the Atlas 5 team.

But it’s doable, he said.

“ULA continues sharpening their pencils and the dates are kind of fluid right now, but they believe that they have about a week-and-half, or just under two weeks, of opportunities for Starliner and the OFT mission beginning on the 17th (of December),” Dunn said. “So they were talking, kind of in rough terms, probably 11 opportunities, maybe the 17th through the 27th before things would then begin to put some pressure on the Solar Orbiter mission.”

Stacking of the Atlas 5 rocket for Solar Orbiter is currently scheduled to begin Jan. 3, Dunn said.

Solar Orbiter has 19 daily launch opportunities through Feb. 23. If the mission is not launched in February, Solar Orbiter’s next opportunity to leave Earth is in October 2020, when the Earth and Venus are again in the correct position in the solar system to enable the spacecraft’s series of planetary flybys.

If the Starliner test flight is delayed more than a couple of weeks, NASA leaders will have to decide whether to prioritize the commercial crew demonstration mission or Solar Orbiter in ULA’s launch manifest. Dunn said teams at Kennedy are providing updates on the Starliner and Solar Orbiter launch opportunities to NASA Headquarters, just in case senior agency managers prioritize one launch over the other.

In addition to the high priority assigned to NASA’s commercial crew program, Solar Orbiter’s limited planetary launch opportunities, the spacecraft’s previous delays, and the international nature of the mission could also factor in to the agency’s decision.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.