SpaceX is set to retire its current fleet of Dragon capsules, in use since 2010, next year and begin flying supplies to the International Space Station on a new variant of the Dragon spacecraft based on the model in development to carry astronauts.

After originally awarding SpaceX a cargo transportation contract in 2008 that eventually totaled 20 Dragon missions, NASA selected the company for a follow-on contract — known as Commercial Resupply Services-2 — in 2016 for at least six additional Dragon deliveries through 2024.

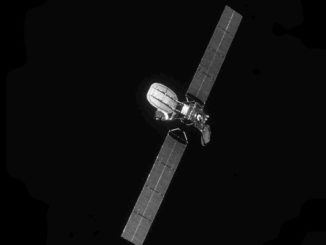

The changeover to SpaceX’s next-generation Dragon — called Dragon 2 or Crew Dragon — for cargo missions next year will come with several benefits, including a faster process to recover, refurbish and re-fly the capsules.

For cargo missions, SpaceX has designed a version of the Crew Dragon, or Dragon 2, spacecraft without SuperDraco abort engines. The launch abort system has been a stumbling block in the Crew Dragon program after a spacecraft exploded during moments before a ground test-firing of the abort engines in April.

SpaceX traced the cause of the explosion to a leaky check valve inside the abort engine pressurization system, but investigators cleared the engines themselves from fault.

The Dragon 2 spacecraft has a different aerodynamic shape than the first-generation Dragon, which first flew in space in 2010, and reached the space station for the first time in 2012. It can also dock automatically with the space station, without requiring station crews to capture it with the research lab’s Canadian-built robotic arm.

The cargo version of Dragon 2 will launch without seats, cockpit controls and other life support systems required to sustain astronauts in space.

Since accomplishing the two Dragon test flights, SpaceX has successfully delivered cargo to the space station 17 times. One mission failed during launch on a Falcon 9 rocket in 2015.

SpaceX shut down the assembly line for the original Dragon spacecraft design in 2017. The company is flying the remaining cargo missions under the original resupply contract with reused Dragon capsules.

SpaceX’s most recent cargo launch, which took off from Cape Canaveral on July 25, was the first to fly a Dragon spacecraft for a third time.

“Dragon 1 is certified for three flights,” said Jessica Jensen, SpaceX’s director of Dragon mission management. “That’s just the maximum we needed with the fleet that already existed.”

Two more resupply missions, designed SpaceX CRS-19 and CRS-20, are scheduled for liftoff in December and next March before the new Dragon 2 vehicle begins flying dedicated cargo missions on the SpaceX CRS-21 mission, currently scheduled for launch next August.

“Then the Dragon 1 fleet is retired, and we switch over to the CRS-2 contract, where we then fly the Dragon 2 vehicle, which is a modified version of the commercial crew vehicle,” Jensen said in a press conference before last week’s Dragon launch. “That one we are going to certify up front to be qualified for five flights, but we’ll just have to see how the manifest works out. But that’s what we’re aiming for at this point in time.”

Jensen said SpaceX tests components on its Dragon cargo vehicles to four times their design lives to certify the spacecraft for three missions.

“We have to make sure that all the hardware on it is qualified for three flights, and we do that early on,” Jensen said. “For example, if there’s a bottle on Dragon that’s going to see 10 pressurization cycles each flight, you have to make sure that it can survive 30 pressurization cycles in a row.

“And when we do that, we test the bottle not only to 30 pressurization cycles, but we multiply that by a factor of four to get to 120,” she said. “So we do that process basically for every component and every subsystem on dragon. We ensure that it has margin to survive all three flights. That’s the first thing we do.”

Like an airliner during maintenance, some parts on the Dragon spacecraft are inspected between flights. Other components are refurbished, and some, like the heat shield, are usually replaced.

SpaceX currently does most of its inspection and refurbishment work on Dragon cargo vehicles at the company’s test site in Central Texas, or at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California.

Beginning with the CRS-21 mission next year, the new Dragon 2 cargo capsules will splash down under parachutes in the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida, rather than the current recovery zone in the Pacific Ocean west of Baja California.

“We plan to do all of the refurbishment (on Dragon 2) here in Florida,” Jensen said. “The fact that we don’t have to transport it to Texas, and to Hawthorne, and back to Florida, that’s going to actually save us a lot of time.

“We have also designed the vehicle from the onset to be easily inspected and refurbished, so the Dragon 2 turnaround times are going to be much faster,” she said.

SpaceX encountered problems with salt water seeping into the Dragon spacecraft during splashdowns earlier in the cargo resupply program.

“With vehicles splashing down in the ocean, you want to minimize salt water intrusion as much as possible,” Jensen said. “I think we’ve learned a lot about how to water seal a vehicle. I think that’s been the biggest (lesson) learned. One is water sealing, and then the other one is accessibility, making sure that you can access the areas that will need to be inspected, and you can do that quickly.

“We learned all of that on Dragon 1 and then designed Dragon 2 from the onset to have better water sealing and easier for access and refurbishment,” Jensen said.

SpaceX does not initially plan to reuse Dragon 2 capsules on missions with astronauts.

Jensen said SpaceX does not foresee any delays in readying the Dragon 2 for cargo missions next year, even if modifications and testing of the abort system needed for piloted flights encounter further schedule slips.

“The cargo Dragon 2 capsule does not have the SuperDraco high-flow abort system,” she said. “So while it is largely the same vehicle, the system that was involved in our in-flight abort test anomaly is not on the cargo Dragon 2 vehicle.

“There is some tie,” she continued. “We want to make sure that everything we learned from that investigation. If there are any susceptibilities, we do want to make sure that those are taken away or covered in the cargo Dragon 2 vehicle. But as of this point in time, we do not anticipate that anomaly investigation to hold up cargo Dragon 2.”

Jensen said SpaceX plans to launch its Dragon 2 cargo missions from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center, the same facility that will host crew launches. That will allow ground teams to load last-minute supplies and time-sensitive experiments into the capsule using the access arm built for astronauts.

SpaceX currently uses a mobile clean room to install the final cargo into the Dragon spacecraft at nearby pad 40.

In addition to SpaceX, NASA also selected Northrop Grumman, other other incumbent cargo transportation provider, for an additional six or more missions to resupply the space station through 2024. Sierra Nevada Corp. won a third contract to ferry cargo to and from the space station using its new Dream Chaser space plane, which will take off on a rocket and land on a runway.

A report by the NASA inspector general last year said SpaceX’s first CRS contract, including provisions for 20 missions, was valued at $3.04 billion, or an average cost of $152.1 million per flight.

The inspector general said the CRS-2 missions, when averaged across all three providers, are projected to cost more than the original slate of cargo flights awarded to SpaceX and Northrop Grumman. The report last year identified increased SpaceX costs, Sierra Nevada’s selection of a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, and higher integration costs as three reasons behind the price hike.

The Dragon 2 spacecraft will be capable of delivering up to 7,290 pounds (3,307 kilograms) of cargo to the space station, including pressurized and unpressurized equipment, according to the NASA inspector general.

But the Dragon 2’s primary arrival mode, using docking rather than capture and berthing with the robotic arm, comes with a limitation.

The hatches through the space station’s docking ports are narrower than the passageways through the berthing ports currently used by Dragon cargo vehicles.

“The docking configuration for Dragon 2 has limitations regarding the size of the hatch such that larger items including spacesuits and large cargo bags cannot fit,” the NASA inspector general said.

Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus supply ship and Sierra Nevada’s Dream Chaser space plane are designed to berth to the space station, offering transportation for bulkier items.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.