The electric sports car shrouded inside the nose of the first Falcon Heavy rocket may conjure notions of a flight of fancy, but SpaceX founder Elon Musk says the powerful new launcher awaiting blastoff Tuesday from Florida’s Space Coast has a lot to prove.

The towering Falcon Heavy, measuring 229 feet (70 meters) tall and 40 feet (12 meters) abreast, sat atop launch pad 39A Monday at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on the eve of its oft-delayed, high-stakes maiden flight.

The Falcon Heavy cuts an imposing figure on the Cape Canaveral landscape, where it awaits liftoff from the same launch pad used by the Apollo 11 moon landing flight and numerous space shuttle missions.

It’s not the biggest rocket in the world — rival United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4-Heavy is taller and wider — but the Falcon Heavy’s 27 main engines pack a heavier punch.

Launch is scheduled during a two-and-a-half hour window Tuesday opening at 1:30 p.m. EST (1830 GMT).

For the Falcon Heavy’s first payload, Musk picked one of his used Tesla Roadsters to shoot into space, not the more typical dummy satellite often carried on test flights.

“It’s just for fun,” Musk said Monday in an interview with CBS News. “A lot of people didn’t understand, what’s the purpose of sending a car to Mars? There’s no point, obviously, it’s just for fun and to get the public excited.

“Normally, when a new rocket is tested they put something really boring on like a block of concrete or a chunk of steel or something,” Musk told CBS News. “All that’s pretty boring. What’s the most fun thing we could put on because this is just a test flight? We’re not going to put any valuable satellites on board. So, the car is just the most fun thing we could think of.”

Musk released an animation of the Falcon Heavy launch Monday, showing the cherry red electric sports car coasting into the cosmos after its shot into interplanetary space. A spacesuit-clad figure is in the driver’s seat, one arm hanging out the window and the other on the Roadster’s steering wheel.

The billionaire shared photos of the figure, which he dubbed “Starman” in apparent reference to the famous David Bowie tune, on Instagram before the automobile’s encapsulation inside the Falcon Heavy’s payload fairing.

Musk announced the Falcon Heavy’s cargo in December, capitalizing on an opportunity for cross-brand marketing between SpaceX and Tesla, his two primary companies.

“I love the thought of a car drifting apparently endlessly through space and perhaps being discovered by an alien race millions of years in the future,” Musk tweeted in December.

Musk said the midnight cherry red Tesla Roadster, which sells for $200,000 brand new, will be playing David Bowie’s iconic hit “Space Oddity” as it soars into the cosmos.

The Falcon Heavy will dispatch the Roadster — weighing around 2,760 pounds (1,250 kilograms) on the street — with enough velocity to escape Earth’s gravitational bonds, reaching a maximum speed of around 7 miles per second (11 kilometers per second; 24,600 mph).

The sports car will go into a “precessing Earth-Mars elliptical orbit around the sun,” SpaceX officials wrote in the mission’s press kit. The orbit will stretch beyond Mars’ average distance from the sun.

“We expect it’ll get about 400 million kilometers away from Earth, maybe 250 to 270 million miles, and be doing 11 kilometers per second,” Musk told reporters Monday. “It’s going to be in a precessing elliptical orbit, with one part of the ellipse being at Earth orbit the other part being at Mars orbit, so it’ll essentially be an Earth-Mars cycler.

“We estimate it’ll be in that orbit for several hundred million years, maybe in excess of a billion years. At times, it will come extremely close to Mars, and there’s a tiny, tiny chance that it will hit Mars,” he said.

Asked if SpaceX has quantified the chance of the Roadster impacting Mars, Musk replied: “Extremely tiny. I wouldn’t hold your breath.”

The Tesla Roadster’s weight and dimensions fall well under the Falcon Heavy’s capacity, and would not stress the lift capability of SpaceX’s smaller, single-core Falcon 9 rocket or Atlas, Delta and Ariane boosters operated by rivals United Launch Alliance and Arianespace.

The iconography surrounding Tuesday’s test launch has captured attention, but star of the show will be the Falcon Heavy itself, set to become the world’s most powerful launcher currently in service.

Comprised of three rocket booster cores derived from SpaceX’s operational Falcon 9 rocket, plus a single-engine upper stage, the Falcon Heavy can generate 5.1 million pounds of thrust in future configurations. On Tuesday’s demo flight, the average thrust from the Falcon Heavy’s 27 kerosene-fueled Merlin 1D engines will be throttled back to 92 percent power, equivalent to roughly 4.7 million pounds, Musk said.

That will surpass the European Ariane 5 launcher, the world’s leader in liftoff power at 2.9 million pound of thrust from two segmented solid rocket boosters and a core engine. SpaceX’s new rocket will produce more thrust than any launch vehicle since the space shuttle, and its power at liftoff — approximately the same thrust as 18 Boeing 747 jumbo jets — will come in fourth among rockets all time, after the Soviet Union’s N1 moon rocket, which never had a fully successful flight, NASA’s Saturn 5 launcher that carried astronauts to the moon, Russia’s 1980s-era Energia rocket and the space shuttle.

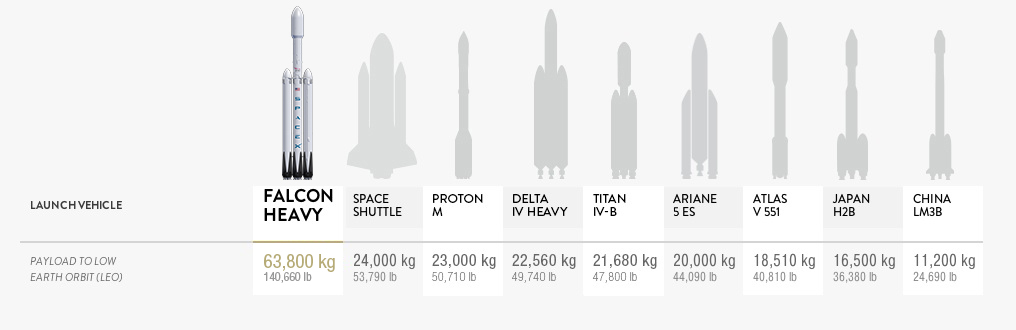

The Falcon Heavy will also be able to carry more payload into orbit than any other rocket in the world — and the most by any launcher since the Saturn 5 — a more important measure of the rocket’s lifting capacity.

The Delta 4-Heavy rocket, the most capable rocket in service today in terms of lift capacity, can haul up to 62,540 pounds (28,370 kilograms) to a low-altitude orbit approximately 120 miles (200 kilometers) above Earth when launched to the east from Cape Canaveral, according to a launch vehicle data sheet published by ULA.

NASA’s planned Space Launch System, set for a maiden flight in late 2019 or early 2020, will carry more than 154,000 pounds (70,000 kilograms) to low Earth orbit and produce a maximum thrust of 8.8 million pounds. A souped-up model of the SLS with an enlarged upper stage launching in the early 2020s could haul more than 230,000 pounds (105 metric tons) to low Earth orbit.

The SLS is being designed with surplus space shuttle engine and booster components, and the space agency intends to use the multibillion-dollar mega-rocket to send astronaut crews to the moon, and eventually beyond.

When its first stage boosters are not recovered, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy will be capable of delivering up to 140,660 pounds (63,800 kilograms) to low Earth orbit when launched to the east from Florida’s Space Coast, where rockets get a velocity boost from Earth’s rotation.

But SpaceX intends to land all three first stage boosters on the Falcon Heavy, eating into the rocket’s propellant reserves and reducing the weight it can loft into orbit.

A Falcon Heavy rocket flight sells commercially for around $90 million, according to SpaceX’s website. But a mission for NASA or the U.S. military, which levy additional requirements on their launch providers, is expected to go for $150 million or more.

A mission using ULA’s Delta 4-Heavy rocket costs at least twice that. A Delta 4-Heavy launch contract for NASA’s Parker Solar Probe awarded in 2015 was valued at $389 million.

Musk predicted the first Falcon Heavy has a 50 to 70 percent chance of full success, but the final outcome of Tuesday’s test flight will only be known more than six hours after liftoff.

“There’s so much that can go wrong here,” Musk told CBS News. “There are a lot of experts out there saying there’s no way you can do 27 engines, all at the same time, and not have something go wrong.

“You’ve got the booster-to-booster interaction, acoustics and vibration that haven’t been seen from any man-made device in a long time,” Musk said.

The Soviet-era N1 rocket had 30 engines, but Russian engineers had trouble getting all of the powerplants to work in unison. Engine vibrations, turbopump failures and fuel leaks led to four failed launch attempts.

By comparison, the Saturn 5 had five larger first stage engines.

Built at SpaceX’s headquarters in Hawthorne, California, the Falcon Heavy will encounter intense structural loads as it climbs to the east from the Kennedy Space Center and exceeds the speed of sound. The moment of maximum aerodynamic pressure, known as Max-Q, will be a major stress point.

The Falcon Heavy’s core stage was manufactured specifically for the test flight. Engineers stiffened the center core to take the loads of a Falcon Heavy launch.

The two side boosters were refurbished and modified after launching two earlier Falcon 9 flights, sending the Thaicom 8 communications satellite and a space station-bound cargo capsule toward orbit in May and July of 2016.

“Around Max-Q, that’s where the force on the rocket is the greatest, and that’s possibly where it could fail as well,” Musk said. “We’re a bit worried about ice potentially falling off the upper stage onto the nose cones of the side boosters. That could be coming like a cannon ball through the nose cones.”

“We’ve done all the (computer) modeling we could think of,” Musk told CBS News. “We’ve asked … third parties to double check the calculations, make sure we haven’t made any mistakes. So, we’re not aware of any issues, nobody has been able to point out any fundamental issues. In theory it should work. But where theory and reality collide, reality wins.”

The Falcon Heavy’s twin boosters will cut off their engines and fall away from the rocket around two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff, a separation sequence that has also never been tested in flight. The core stage, operating a lower throttle setting to conserve propellant and burn longer, will continue firing its nine engines until T+plus 3 minutes, 4 seconds.

“If it clears the pad and hopefully makes it throgh transonic and Max-Q, and the boosters are able to separate, it’s a more normal regime,” Musk said. “It becomes like a Falcon 9 at that point.”

The upper stage’s single Merlin engine will fire three times on Tuesday’s mission, continuing the demo flight’s experiments well after liftoff.

Meanwhile, the Falcon Heavy’s two strap-on boosters will flip around to fly tail-first with the aid of cold-gas nitrogen thrusters. Some of the engines on each booster will reignite for “boostback” and “entry” maneuvers to aim for two adjacent touchdown zones at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station around 9 miles (13 kilometers) south of pad 39A.

Like the Falcon 9’s first stage, the boosters will unfurl grid fins for added stability.

Twin sonic booms will crack across the spaceport as the boosters return to Cape Canaveral for staggered landings, slowed with the help of rocket thrust.

The rocket’s center core will head for touchdown on SpaceX’s drone ship positioned downrange in the Atlantic Ocean, with landing expected at T+plus 8 minutes, 19 seconds, approximately 20 seconds after the boosters arrive back on the ground at Cape Canaveral.

The second stage engine will shut down to conclude its first burn at around T+plus 8 minutes, 31 seconds. Another 30-second firing is programmed to start at T+plus 28 minutes, 22 seconds, to send the upper stage, its Tesla cargo and “Starman” into an orbit that ranges to a peak altitude tens of thousands of miles above Earth.

But the mission will not be over.

The rocket will keep flying, soaring through the Van Allen radiation belts before its engine reignites around six hours later for a departure maneuver into interplanetary space.

Musk said the extreme cold and radiation will present hazards during the six-hour coast, which is twice as long as any profile followed by a Falcon 9 rocket in the past.

“Even once we reach orbit we’ve got a very long coast, we’ve got a six-hour coast before restart, which is twice as long as we’ve ever coasted a stage, so we could see the fuel potentially freeze, because it’s out there in deep space, and when it’s not facing the sun it’s at three degrees above absolute zero,” Musk told CBS News. “So it could easily freeze, or the liquid oxygen could boil off, so there’s a lot that could go wrong.”

The upper stage “will actually be in a far worse radiation environment than deep space for several hours, survive that, and then re-light for the trans-Mars injection,” he said.

Long-duration upper stage flight profiles are required for the most demanding U.S. military launch missions, such as the placement of satellites directly into geostationary orbit, a circular perch more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator. Multiple, perfectly-timed engine burns are needed to move from an initial low-altitude inclined parking orbit into such a high-altitude equatorial position.

The lengthy upper stage flight Tuesday will try to demonstrate the Falcon rocket family’s capability to pull off such a feat, showcasing the performance to the Air Force and other prospective customers.

Musk said the upper stage carries additional battery power and pressurant gas for the extra operating time in space.

Musk unveiled the Falcon Heavy rocket in 2011, and proclaimed then the launcher would be ready for blastoff in 2013. SpaceX said it slowed development of the Falcon Heavy to focus on other projects, including the recovery of Falcon 9 rocket stages for reuse, and to resolve technical problems that destroyed two Falcon 9 rockets in 2015 and 2016, one in flight and another on the launch pad.

Musk announced in September his updated vision for settling Mars — SpaceX’s ultimate mission — and announced that his company is working on a giant new rocket dubbed the BFR that could send cargo and crew ships to the red planet, or perhaps the moon if a lunar base becomes reality.

SpaceX developed the Falcon Heavy to lift heavier payloads into space than the company’s Falcon 9 rocket, and to compete with other heavy-lifters for contracts to haul massive spacecraft for the U.S. military and NASA. The Falcon Heavy may also find a niche in deploying large commercial satellites, or launching clusters of smaller spacecraft to support the build-out of planned broadband communications networks.

“This rocket’s great for a lot of reasons,” Musk told CBS News. “It’s something that I think inspires the public. I’ve been asked, is this like Apollo? I’d say it’s not Apollo, but it’s arguably a prelude to a new Apollo, and it’s going to be the only heavy to super-heavy lift rocket in the world. This will be more than twice the thrust and capability of any other rocket currently flying. And if it reaches orbit, it will have the most payload of any rocket since the Saturn 5.

“You could actually send people back to the moon with the Falcon Heavy. You could, with orbital refueling, send people to Mars,” he said. “We think probably our next design, the BFR, is going to be ideal for interplanetary colonization and for establishing a large base on the moon and a city on Mars,” he said. “But this is a prelude to that. This is going to teach us a lot about what’s necessary to have a huge booster with a crazy number of engines.

“We finally have a major advancement in rocketry … I’m not sure whether this will be lost on people, whether they’ll appreciate it,” he said. “I hope they do, because the era of the very large rocket went away with Saturn 5 and with the space shuttle. I find it odd that the Falcon Heavy is twice the thrust of anything from Russia, China, Boeing, Lockheed or Europe. And I hope it encourages them to raise their sights.”

Going into Tuesday’s test flight, only three Falcon Heavy missions are confirmed in SpaceX’s backlog after the test launch: Two for commercial telecom companies Arabsat and ViaSat, and one for the Air Force. Another company, Inmarsat, has an option to launch a future satellite on a Falcon Heavy.

Some customers that reserved launches on SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket switched their satellites to the smaller Falcon 9, which benefited from multiple thrust and performance upgrades to carry some payloads that originally required the triple-core rocket.

Inmarsat and Intelsat had planned launches on the Falcon Heavy, but both ended up flying their satellites on the Falcon 9. The ViaSat 2 satellite built to provide high-speed Internet access across the United States was supposed to launch on a Falcon Heavy, but the firm move its launch to a European Ariane 5 rocket, citing schedule worries. ViaSat retained its contract with SpaceX to launch a future satellite on a Falcon Heavy.

Musk told CBS News he was “giddy” on the eve of the Falcon Heavy’s first blastoff.

“I thought for sure something would delay us, we could have some issue we discovered on the rocket or maybe bad weather,” Musk said in a conference call with reporters Monday afternoon. “But the weather’s looking good, the rocket’s looking good, so it should be an exciting day. I’m looking forward to it.

“We’ll have a good time no matter what happens. It’s guaranteed to be exciting, one way or another. It’s either going to be an exciting success or an exciting failure. One big boom! I’d say tune in, it’s going to be worth your time.”

But he’s hopeful for success.

“We’ve done everything we can,” Musk said. “I’m sure we’ve done everything we could do to maximize the chances of success of this mission. I think once you’ve done everything you can think of and it still goes wrong, well, there’s nothing you could have done. But I feel at peace with that.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.