A powerhouse communications satellite owned by Inmarsat has been fueled for liftoff on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket Monday from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on a mission to provide broadband links for passengers and crews aboard ships and airplanes, while technicians are loading space station-bound supplies into a commercial Dragon cargo capsule and preparing a Bulgarian telecom for launch on two other SpaceX boosters by mid-June.

The launch for London-based Inmarsat on Monday is the first of four SpaceX missions slated to blast off by the end of June from launch pads in Florida and California. The quick launch cadence, if achieved successfully, will put a dent in SpaceX’s backlogged manifest, which officials say stands at 70 missions worth more than $10 billion, figures that apparently include the company’s lucrative contract to develop a human-rated spaceship to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station.

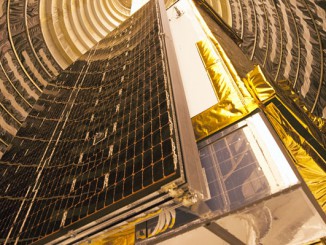

Since arriving at the Florida launch base last month, the Boeing-built Inmarsat 5 F4 communications station was filled with 5,372 pounds (2,437 kilograms) of hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants during a four-day procedure inside SpaceX’s payload processing facility at Cape Canaveral.

Technicians lifted the spacecraft on the Falcon 9’s payload adapter, made by Ruag Space in Sweden, ahead of encapsulation this week inside the rocket’s composite payload fairing. The adapter is fitted with a ring connecting the Inmarsat 5 F4 spacecraft to the Falcon 9’s second stage.

Meanwhile, SpaceX workers inside the Falcon 9 hangar at nearby launch pad 39A were mounting the two-stage booster on a mobile transporter-erector Wednesday. SpaceX intends to roll out the rocket to pad 39A for a customary fueling test and a hold-down engine firing as soon as Thursday.

The Falcon 9’s Merlin 1D main engines will ignite for more than three seconds as clamps keep the rocket grounded. Engineers plan to analyze the performance of the rocket before clearing it for liftoff Monday.

After the hotfire test, crews will return the Falcon 9 to the hangar at the southern perimeter of pad 39A, where the Inmarsat 5 F4 satellite and the rocket’s nose fairing will be attached. The rocket’s final rollout to the historic launch complex, previously used by Saturn 5 moon rockets and space shuttles, is expected Sunday or early Monday.

The 50-minute launch window Monday opens at 7:20 p.m. EDT (2320 GMT).

The heavy weight of Inmarsat 5 F4 — more than 13,000 pounds, or around 6 metric tons — will prevent the Falcon 9 rocket’s first stage booster from attempting a landing on SpaceX’s recovery vessel in the Atlantic Ocean. The booster is not expected to launch with landing legs, grid fins, or other hardware needed for descent maneuvers.

Inmarsat 5 F4 will deploy into an oval-shaped geostationary transfer orbit, with a low point a few hundred miles above Earth and an apogee tens of thousands of miles in altitude. The craft’s on-board hydrazine-fueled engine will circularize its orbit at an altitude of nearly 22,300 miles (around 35,800 kilometers) over the equator.

Monday’s launch will be the sixth SpaceX mission this year. The company’s founder and chief executive, Elon Musk, said in late March that SpaceX planned between 20 and 25 rocket flights in 2017, aiming to average missions every two weeks or so.

The rapid-fire launch campaigns have long been promised by SpaceX, but two rocket failures in June 2015 and September 2016 grounded the company’s missions for months, combining to set back its manifest by nearly one year.

Shorter delays stemming from satellite issues, rocket production bottlenecks, and the difficulty of scheduling launches to the International Space Station have also stricken SpaceX. NASA must weigh the readiness of station astronauts and other missions heading to the orbiting research outpost when approving launch dates for SpaceX’s Dragon supply ships.

But SpaceX now has a surplus of customers with payloads ready for launch.

Managers from the launch company’s biggest commercial client, Iridium, said last month that half of the firm’s 81 next-generation communications satellites have been constructed by Thales Alenia Space and Orbital ATK at a factory in Arizona. The first batch of 10 Iridium Next spacecraft were launched into orbit a few hundred miles above Earth in January on a Falcon 9 rocket, and the rest await Falcon 9 rides into orbit from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California promised by SpaceX every two months beginning June 29.

Intelsat officials said in an April 27 conference call with investors that the Boeing-made Intelsat 35e communications satellite, the fourth in the operator’s new-generation “Epic” high-throughput relay satellites, is scheduled for a Falcon 9 launch in late June from Florida.

But first comes three Falcon 9 flights with launches targeted for Monday, June 1 and June 15.

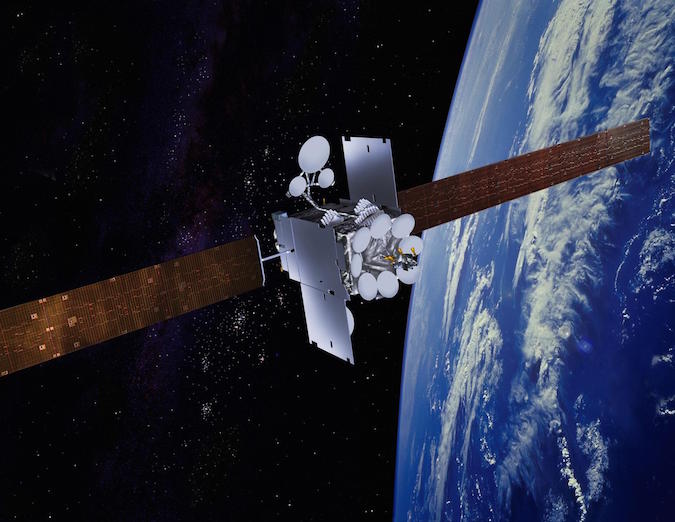

The fourth member of Inmarsat’s Global Xpress network, a $1.6 billion, four-satellite update to the operator’s geostationary fleet, will add back-up capacity and new business opportunities to the London-based company’s constellation following its launch Monday.

Based on the Boeing 702HP satellite bus, Inmarsat 5 F4 joins three nearly identical spacecraft successfully orbited on three Russian Proton rockets from 2013 through 2015 under the auspices of International Launch Services, a U.S.-based, Russian-owned launch services provider.

The first three Inmarsat 5-series satellites are parked in geostationary orbit at positions around the globe. The first Global Xpress satellite is positioned to cover Europe, the Middle East and Africa, the second is over the Atlantic Ocean and the Americas, and a third Inmarsat 5 satellite launched in August 2015 provides coverage to the Asia-Pacific and Australia.

Rupert Pearce, Inmarsat’s CEO, said May 4 that Inmarsat 5 F4 will probably begin service over Europe, supplementing the Inmarsat 5 F1 satellite’s coverage there.

Pearce said there is a “strong business case” for locating the new satellite over Europe, but he said Inmarsat has not solidified its plan for Inmarsat 5 F4.

“Because it’s not needed (for) complete global coverage, the role of Inmarsat 5 F4 could change through its life,” said Tony Bates, Inmarsat’s chief financial officer, in a May 4 quarterly conference call with investment analysts. “And obviously, they are for in-orbit redundancy, which would limit it if it was needed for that purpose. But otherwise, it can go off to discrete business opportunities that may differ during its life.”

The major customers for the Global Xpress network — Inmarsat’s fifth-generation fleet — include airlines, which use satellite links for safety and passenger entertainment, the maritime industry, oil and gas platforms, media companies, and the military.

Boeing is responsible for selling Global Xpress services to U.S. government and military users.

Each Inmarsat 5-series satellite carries 89 fixed and steerable spot beams in Ka-band. The company’s earlier satellites broadcast in L-band, but Inmarsat switched to Ka-band for the Global Xpress system, offering improved downlink communications speeds to 50 megabits per second, with up to 5 megabits per second on the uplink side.

Inmarsat 5 F4 was originally supposed to launch in 2016 on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, a triple-core booster formed by three Falcon 9 first stages. But the heavy-lifter still has not flown, and Inmarsat transferred the Inmarsat 5 F4 launch to a smaller Falcon 9, forcing SpaceX to forego recovery of the first stage booster on the coming flight in order to lift the Global Xpress satellite into orbit.

Inmarsat in December switched another satellite that was slated to fly on a Falcon Heavy to launch on an Ariane 5 rocket owned by rival Arianespace.

Next in line on SpaceX’s manifest is the June 1 launch of a robotic Dragon supply ship to the International Space Station. Technicians are spending this month installing cargo into the pressurized carrier, while three experiment modules have already been loaded into the spaceship’s unpressurized trunk section.

The upcoming cargo delivery, SpaceX’s 11th revenue-earning supply launch to the space station, will be the first to use a previously-flown Dragon capsule. The pressure shell containing the mission’s internal supplies first flew on SpaceX’s fourth cargo mission in September 2014.

The Dragon’s external cargo section burns up in Earth’s atmosphere at the end of each mission.

SpaceX engineers retrieved the capsule in the Pacific Ocean after 34 days in space, refurbished the spacecraft for another flight, then shipped the cargo module back to Cape Canaveral for launch preps.

A NASA spokesperson said SpaceX’s 11th resupply flight, set for launch from pad 39A around 5:55 p.m. EDT (2155 GMT) on June 1, will loft around 5,879 pounds (2,667 kilograms) of equipment, provisions and experiments to the space station and its crew.

The cargo manifest breaks down to 3,670 pounds (1,665 kilograms) of supplies inside Dragon’s pressurized compartment, and 2,209 pounds (1,002 kilograms) of equipment in the disposable spacecraft trunk.

Astronauts inside the station will unpack Dragon’s internal cabin, while robotic arms outside the complex will extract three payloads from the trunk after the ship arrives at the outpost a few days following liftoff.

The experiment packages to be bolted on platforms outside the station include NICER, an astrophysics investigation that NASA says “will measure neutron stars and test, for the first time in space, technology that uses pulsars as navigation beacons.”

Another payload is the Roll-Out Solar Array developed by Deployable Space Systems of Santa Barbara, California, with support from the U.S. Air Force. The experimental array is a new type of power-generating solar panel that unrolls like a party favor, making it more compact than rigid designs currently flying on satellites.

A commercially-built Earth-viewing camera system from Teledyne Brown that will host multiple digital imagers and hyperspectral sensors will also be launched on the Dragon for attachment to a post outside the space station.

The Dragon cargo craft will spend about a month berthed to the space station’s Harmony module, near a commercial Cygnus cargo freighter from Orbital ATK that is already attached to the lab’s Unity module.

SpaceX’s next reused rocket booster is preparing for launch on the afternoon of June 15 from Kennedy Space Center with BulgariaSat 1, Bulgaria’s first communications satellite.

The nearly 9,000-pound (4-metric ton) spacecraft, built by Space Systems/Loral, will broadcast television channels to homes in Bulgaria, Serbia and elsewhere in Europe for BulgariaSat, an affiliate of Bulsatcom, Bulgaria’s largest digital television provider.

Nearly 12 years in the making, the $235 million satellite project is a big step for Bulgaria, according to Maxim Zayakov, BulgariaSat’s CEO.

“The satellite is a huge thing,” Zayakov said in a May 5 interview with Spaceflight Now. “It’s a big milestone and gives us a chance for regional development … as well as throughout Europe, where we have our main coverage. And for the country, definitely, it’s the first geostationary communications satellite.”

Zayakov said BulgariaSat 1 was also a victim of SpaceX delays following a Sept. 1 rocket explosion on a launch pad at Cape Canaveral, which destroyed the Amos 6 communications satellite owned by Israel-based Spacecom Ltd.

“We were just given a launch date, which previously was Nov. 28, and we received confirmation of that launch date on Aug. 30,” Zayakov said. “Not long after that, neither our friends at Spacecom nor us had anything. They didn’t have a satellite, and we didn’t have a launch date.”

Zayakov said the successful re-flight of a SpaceX Falcon 9 first stage booster with the SES 10 communications satellite March 30 “confirmed the whole concept” of reusability.

“Now, it is obvious that the cost of reaching space is certainly going to be even lower,” Zayakov said. “SpaceX was already setting new standards in that regard, and now it’s even better.

“It really is a big deal,” he continued. “A lot of people don’t realize that, for small countries and small companies like us, without SpaceX, there was no way we would ever be able to even think about space. With them, it was possible. We got a project. I think, in the future, it’s going to be even more affordable because of reusability.”

According to Zayakov, SSL made the arrangements to launch BulgariaSat 1 on a previously-flown rocket prior to the much-watched SES 10 mission. The California-headquartered satellite manufacturer is SpaceX’s direct customer for the mid-June mission, while BulgariaSat will take command of the spacecraft once it is in orbit.

“SpaceX told them all the pros and cons (of using a previously-flown rocket), and I believe they were waiting for a confirmation from the insurance community,” Zayakov said. “I think that’s why it was decided to take the second reused flight, and not the first.”

At the time of the Friday interview, Zayakov said BulgariaSat 1 was en route from its factory in Palo Alto, California, to the Florida spaceport for fueling and other preflight processing.

Iridium and Intelsat’s satellites are on track for launch on Falcon 9 rockets by the end of June, and SpaceX plans around two missions per month the rest of the year, a backlog primarily populated by commercial telecom payloads, more Dragon logistics flights to the space station, and one or two launches of the new Falcon Heavy rocket.

Falcon 9 customers are now more willing than ever to disclose specific launch dates weeks or months in advance, a sign that SpaceX may finally be hitting its stride after several years of missed launch targets, at least in the eyes of several major clients.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.