A Falcon 9 booster that flew into space last year is set to launch again Thursday from Florida’s Space Coast with an SES communications satellite on a historic mission that could make major strides in validating SpaceX’s audacious goal of recovering and reusing launchers, an achievement the company says will revolutionize the rocket business.

Like all launches, the flight is risky, but SES officials and insurers are comfortable enough to put an operational satellite on-board.

Martin Halliwell, chief technology officer of Luxembourg-based SES, said this week that he believes the risk has been blunted by months of inspections, refurbishment and engineering reviews.

“We’ve been through this thing with a fine-toothed comb,” Halliwell said Tuesday. “SpaceX has been through this with a fine-toothed comb. This booster is a really good booster, and we’re confident in this one.”

Since its first launch on April 8, 2016, the first stage booster has been inspected, partially taken apart and refurbished, and re-tested at SpaceX’s rocket development facility in McGregor, Texas. Despite the rework, Halliwell said the stage remains “original.”

Thursday’s launch will be the first time an orbital-class commercial rocket has been reused. SpaceX has retrieved eight Falcon 9 first stages in 13 tries since 2015, and the company says it could re-fly up to six of the boosters this year to gain experience and make headway in cost reductions, the purpose behind recovering and reusing rocket hardware.

But those plans depend on what happens Thursday.

“We’re here at the edge of quite a significant bit of history,” said Halliwell, a 30-year veteran of the satellite industry.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) rocket, sporting a newly-built upper stage and payload fairing, is set to blast off from launch pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 6:27 p.m. EDT (2227 GMT) Thursday.

The launch window extends two-and-a-half hours, and forecasters predict an 80 percent chance of favorable weather. A backup launch opportunity is available Saturday.

The SES 10 satellite, manufactured in France by Airbus Defense and Space, is set to begin at 15-year mission broadcasting television services across Latin America.

Burning a mixture of super-chilled, densified RP-1 kerosene fuel and liquid oxygen, the two-stage rocket will climb away from Central Florida on 1.7 million pounds of thrust, exceed the speed of sound just after the flight’s one-minute point, and shed its first stage less than three minutes into the mission.

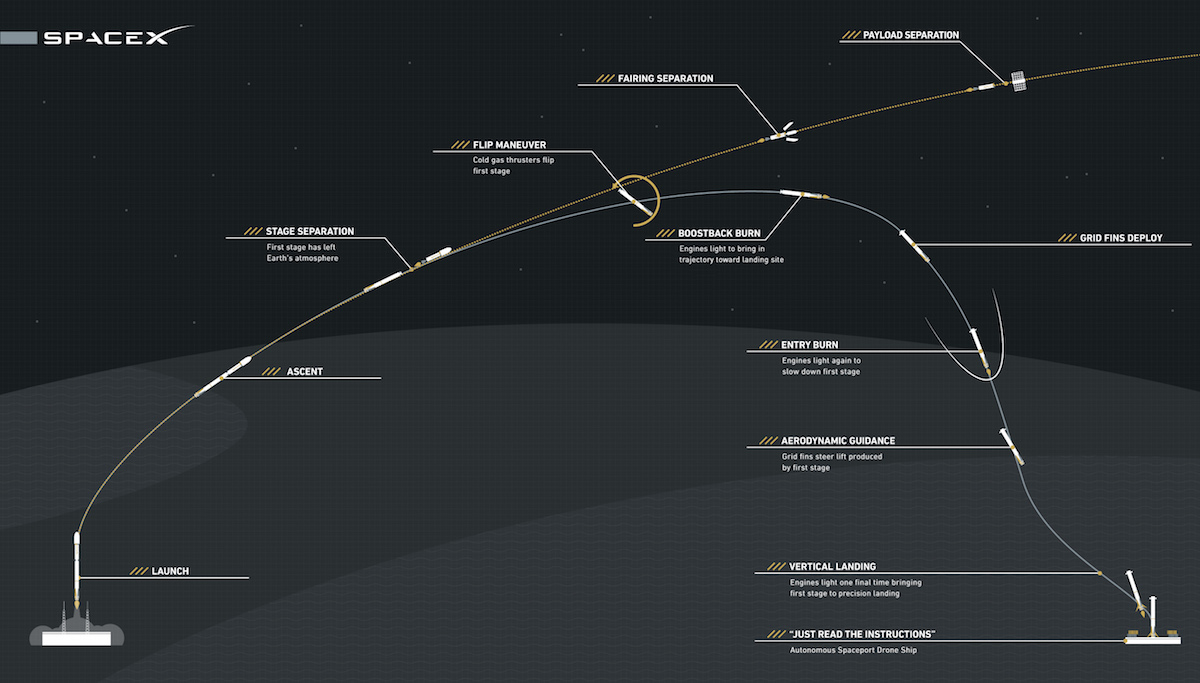

Repeating its up-and-down trajectory on its first flight last year, the rocket booster will aim for landing on SpaceX’s drone ship around 340 miles (550 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral.

The Falcon 9’s second stage, powered by a single Merlin 1D engine, will fire two times to deploy SES 10 into an oval-shaped geostationary transfer orbit ranging between 135 miles (218 kilometers) and 22,002 miles (35,410 kilometers) in altitude, according to Halliwell.

The rocket will inject SES 10 into an orbit with a tilt of about 26.2 degrees to Earth’s equator. Separation of the satellite from the launcher is programmed for 32 minutes after liftoff.

The 11,644-pound (5,282-kilogram) satellite will fire its own engine to circularize its orbit nearly 22,300 miles (about 35,800 kilometers) over the equator in April. At that altitude, SES 10 will move around Earth at the same speed the planet rotates, allowing it to remain in a fixed geographic location.

Once it completes in-orbit testing, SES 10 should be operational by mid-May, Halliwell said, in a slot at 67 degrees west longitude, giving the spacecraft’s antennas and Ku-band transponders visibility from Mexico and the Caribbean to the southern tip of Argentina.

“This is an extremely important satellite for SES and the development of our business in Latin America,” Halliwell said. “Predominately, this is going to be for video, and predominately, this is going to be for the development of the Ultra HD capability of SES into these various different areas.”

If the rocket lands smoothly on Thursday’s mission, SpaceX could reuse it a third time. SES officials also hope to get a piece of the booster to display inside the company’s board room in Luxembourg.

The relatively heavy weight of the SES 10 satellite, coupled with the mission’s high-altitude target, will leave little fuel inside the first stage for the landing maneuvers.

“We’re right at the limit from a mass point-of-view,” Halliwell said. “It’s going to be a pretty hot mission to try to bring this back.”

All that hinges on the performance of the Falcon 9, which SpaceX designed to be reusable from the start.

Thursday’s flight will be 32nd launch of a Falcon 9 rocket since June 2010. All but one of those missions have succeeded in their primary objective, but that tally does not count a catastrophic rocket explosion on a launch pad last year, a mishap that destroyed an Israeli communications satellite and grounded SpaceX launch operations more than four months.

Engineers initially tried to recover the first stage boosters by parachute in the Atlantic Ocean, then changed the concept to land the rockets vertically on ocean-going barges, or back at the launch site.

On a normal launch, the first stage burns more than two-and-a-half minutes to accelerate the Falcon 9’s upper stage and payload toward orbital velocity. The lower booster, stretching around 156 feet (47 meters) long, detaches from the second stage and typically arcs to a peak altitude of more than 60 miles — more than 100 kilometers — before coming back to Earth.

Thrusters pulsing with cold nitrogen gas flip the stage around to travel tail first, and a subset of its nine Merlin 1D engines reignite in a series of burns to slow its descent. Grid fins mounted around the circumference of the booster help steer the rocket toward its destination, and four landing legs extend just before touchdown.

The booster selected to launch the SES 10 satellite was the first to successfully land at sea after sending a Dragon supply ship toward the International Space Station. SpaceX recovered its first rocket in December 2015 on a landing pad at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, and the company put that vehicle on vertical display outside its headquarters building in Hawthorne, California.

SpaceX founder and chief executive Elon Musk revealed his revamped rocket reuse plan in September 2011.

“There have been the naysayers,” Halliwell said. “There have been people that have said to me it’s impossible … Well, here we are. Never say never, right?”

Musk likes to compare rockets to airplanes, often referring to the expense of throwing away an airliner after a single flight. His long-term vision is to set up a human base on Mars, followed by settlement, and those lofty ambitions require dramatic reductions in the cost of space transportation.

“I think this was a really good milestone for the future of spaceflight,” Musk said after last April’s landing of the rocket stage set to fly again Thursday. “I think it’s another step toward the stars. In order for us to really open up access to space, we’ve got to achieve full and rapid reusability.”

NASA’s space shuttle orbiters flew dozens of times, but they took months to reconfigure between missions at significant cost, requiring thousands of engineers and technicians in hands-on jobs and in support roles.

“Being able to (rapidly reuse) the primary rocket booster is going to be a huge impact on costs,” Musk said. “It’ll obviously take us a few years to make that smooth and make it efficient, but I think it’s proven that it can work.”

SpaceX spent about four months refurbishing the rocket last year, according to Gwynne Shotwell, the company’s president and chief operating officer. Managers hope to cut that turnaround time significantly for future reuse missions.

SES and SpaceX agreed to put the SES 10 spacecraft on a previously-flown rocket booster in August 2016, days before the launch pad explosion that suspended Falcon 9 flights for the rest of the year.

But SES, operator of around 56 satellites currently in orbit, stuck by its commitment to purchase a flight of a reused rocket.

While SpaceX and SES did not disclose terms of their contract for the SES 10 launch, Shotwell said last year the launch provider was offering a 10 percent discount for customers willing to fly their payloads on reused boosters.

That discount should become steeper on future flights as engineers hasten turnarounds, according to SpaceX officials. The company lists a regular commercial Falcon 9 flight at $62 million.

Halliwell acknowledged that SES received a discount in exchange for agreeing to the launch aboard a previously-flown rocket, but he said SES’s decision was strategic.

“It’s not just the money in this particular case,” Halliwell said. “It’s really (about) getting this proof of concept moving. Someone has to go first, and SES has a long history of doing this.”

SES was the first commercial satellite company to put one of its payloads on a Russian Proton rocket in 1996. More recently, SES launched a spacecraft on SpaceX’s first mission to geostationary transfer orbit, the drop-off point for most communications satellites, in December 2013.

Halliwell said SES and SpaceX convinced insurers that the risk of launching on a used rocket was little more than that of a normal rocket flight. He said there was “no material change” in the insurance rate after SES decided to launch a satellite on SpaceX’s “flight-proven” booster.

“I’m talking hundredths of a percent,” Halliwell said. “There was essentially no change in the insurance premium.”

“We have to sit with our insurers, and we have to explain to them our level of confidence, and why we have that level of confidence,” Halliwell said.

“You can look at it two ways,” said one insurance underwriter who works in the satellite and launch markets. “You can be optimistic, and glass half-full, and say it’s a stage that’s been flight-tested, and that’s the ultimate test, and it came back, so it should be great. The glass half-empty view is that it’s already been used, and it’s seen a lot of exposure to the elements with vibration, rust and things like that.

“We have to be optimistic about it,” the insurance official said. “SpaceX really is committed to this, as Blue (Origin) will be, so we have to face it … SES is the biggest satellite operator out there, and if they’re going with it, they are probably comfortable enough with it. There may be an increased risk of loss. I don’t know. We’ll see.”

SpaceX kept the insurers in the loop on its progress.

“We, as insurers, didn’t really raise much of a fuss once we’d been briefed,” the underwriter told Spaceflight Now.

“We’ve had some some very in-depth conversations with SpaceX about their process for re-qualifying, and their process for refurbishment. We’re convinced that, No. 1, they’re committed to it, and No. 2, they’re serious about it. So they’ve done what we wanted them to do.”

SpaceX did not swap out any of the rocket’s nine Merlin 1D engines, and SES engineers were embedded with the launch company over the last few months. Halliwell said SpaceX gave the SES engineers — all U.S. citizens to comply with arms export regulations — “tremendous transparency” into the design of the engines and avionics, along with test results.

“We’ve tested this thing, we’ve run the engines up, we’ve looked at the airframe, we’ve looked at all the various components, and this thing is good to go,” Halliwell said. “We don’t believe we’re taking an inordinate risk here.”

If Thursday’s launch is successful, Halliwell said SES might launch two more satellites — SES 14 and SES 16 — on previously-flown boosters later this year. The next SES satellite assigned to a SpaceX launch — SES 11 — will fly this summer on a newly-manufactured rocket, he said.

“I think a bunch of companies are waiting to see (what happens),” the insurance underwriter said. “A lot of it does have to do with the insurance market. If this goes successfully, then a lot of customers are going to assume that the insurance community is OK with reused stages, which will be the case.

“We embrace it, and we encourage it,” the insurance official said. “What we want our clients to do is go in with their eyes wide open and not be fooled by the fluff that SpaceX may lay on them about how this is risk-free and all that kind of stuff.”

SpaceX’s government customers — NASA and the U.S. Air Force — so far have not agreed to fly their payloads on reused rockets.

Nevertheless, the insurer said the push toward reusable rockets is unlikely to be reversed, even by a failure.

“The bottom line is reused rockets are here to stay,” the underwriter said.

Blue Origin, the space company founded by Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos, is developing the powerful New Glenn rocket for a maiden flight from Cape Canaveral in 2020. The methane-fueled New Glenn, named for Mercury astronaut John Glenn, will land on an offshore platform for reuse in a manner similar to the concept pioneered by SpaceX.

More entrenched rocket companies are taking a more conservative approach to reuse.

United Launch Alliance, a 50-50 joint venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin, is working on the next-generation Vulcan rocket, which is likely to be powered by Blue Origin-built BE-4 engines. The initial Vulcan flights will be expendable, but ULA is studying a way to retrieve the engines with a heat shield and a parachute.

Europe’s new Ariane 6 rocket will be single-use when it debuts in 2020, but the European Space Agency, the French space agency CNES and Airbus Safran Launchers have partnered to work on the reusable Prometheus engine, which could be installed on a future European booster outfitted to fly multiple times.

“What we want to do is encourage the launcher industry to follow this way forward,” Halliwell said. “Maybe Bezos will be able to do this. Maybe, one day, Ariane will be able to to this. I don’t know. But right now, tomorrow or the day after, we’re going to try and do this thing.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.