An interplanetary space weather station rocketed away from Cape Canaveral aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket Wednesday, speeding toward a remote operating post a million miles from Earth to help forecasters warn of intense solar storms.

The $340 million mission will collect data on the solar wind — a stream of particles constantly streaming away from the sun — giving officials notice when solar storms could disrupt communications, trigger power outages, or endanger polar air traffic and satellites.

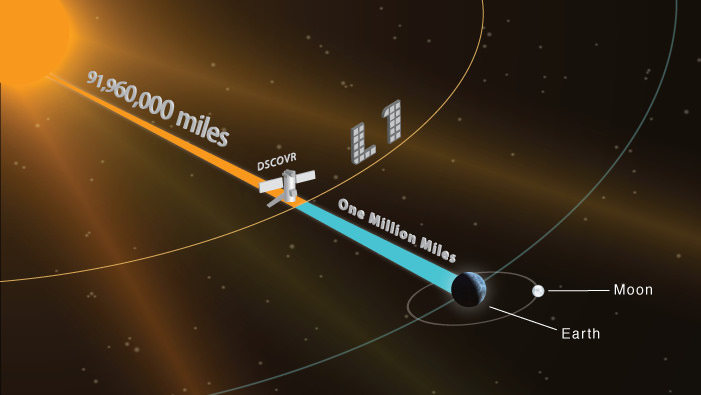

The Deep Space Climate Observatory is heading for the L1 Lagrange point, a gravitationally-stable point nearly one million miles from Earth in line with the sun.

“From this location, DSCOVR will provide forecasters with critical information about the supersonic solar wind that continually streams from the sun to interact with Earth’s magnetosphere and upper atmosphere,” said Tom Berger, director of NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colorado. “Most of us know this interaction through its generation of the aurora borealis, or Northern Lights, the most visible aspect of space weather.

But solar activity can drive more than the picturesque Northern Lights.

Officials have blamed electrical blackouts on space weather, satellites have been knocked offline by solar eruptions, and geomagnetic storms have forced airlines to re-route planes away from Earth’s poles.

“DSCOVR will also serve as our tsunami buoy in space, if you will, giving forecasters up to an hour’s warning of these huge magnetic eruptions from the sun that ocacsionally occur, called Coronal Mass Ejections, or CMEs,” Berger said.

The Deep Space Climate Observatory, managed by NOAA in partnership with NASA and the U.S. Air Force, blasted off at 6:03 p.m. EST (2303 GMT) Wednesday, a few days later than scheduled after a radar outage and stiff high-altitude winds kept the Falcon 9 rocket grounded.

The 224-foot-tall rocket’s nine Merlin 1D engines powered up to full thrust and cast an orange glow across the Florida spaceport a few minutes before sunset, rising into a deep blue sky trailing a 30-story plume of fiery exhaust.

Illuminated by the setting sun, the slender kerosene-fueled launcher climbed into the stratosphere, sending out a reverberating roar audible to observers for dozens of miles.

![EyeTVSnapshot[739]](http://spaceflightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/EyeTVSnapshot739.jpg)

The booster was supposed to target a propulsive landing on SpaceX’s barge in the Atlantic Ocean, but rough seas forced officials to call off the attempt, which engineers planned to use to refine rocket recovery procedures for a future reusable launch system.

The first stage instead aimed for a point in the open ocean, and SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk tweeted that the rocket nailed it, hitting its mark with less than 10 meters (33 feet) of error a few hundred miles off Florida’s East Coast.

SpaceX did not expect to able to retrieve the rocket intact due to the high waves.

Part of the rocket’s flyback maneuver was visible to spectators on the ground, as was the release of the Falcon 9’s clamshell-like payload fairing about three-and-a-half minutes after liftoff.

Sunshine at the high altitude of the launcher lit up the rocket stages and fairing halves as they jettisoned and trekked east-northeast from Cape Canaveral.

The Falcon 9 second stage shut down its engine less than nine minutes into the flight, coasted across the Atlantic Ocean, then re-ignited for about a minute to propel the refrigerator-sized DSCOVR spacecraft on an arcing 110-day path to a position nearly a million miles form Earth.

The space weather observatory’s launch came after a nearly two-decade wait for a ride into space.

Originally proposed by former Vice President Al Gore in a speech at MIT in March 1998, DSCOVR has gone through stops and starts and weathered a political maelstrom in Washington before riding a rumbling rocket into space.

Gore envisioned a camera positioned at L1, beaming down live views of the planet on the Internet. The camera, he said, would show Earth’s fragility backdropped by the austere blackness of space, and help inspire people around the world.

Republican lawmakers criticized the project as a high-priced “screen saver” and named the mission as one of Gore’s pet projects.

Congress halted the project — which Gore named Triana after one of the sailors on Columbus’s 1492 voyage to the new world — in late 1999 for a review of the mission’s scientific merit by the National Research Council.

After George W. Bush’s election as president in 2000, NASA suspended work on Triana in 2001. The spacecraft was transferred to a clean room at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in November 2001, where it was stored under nitrogen purge conditions until it was removed for testing in November 2008.

Triana was renamed DSCOVR before NASA quietly cancelled the mission in 2005, citing the dwindling number of remaining shuttle flights to put it on, and a lack of funding to refurbish and launch the satellite.

Worried that NASA’s Advanced Composition Explorer supplying critical data to space weather forecasters could fail at any time, NOAA started studying how to replace the aging ACE mission. It turned out the most affordable option was to take Gore’s bainchild out of its storage container for refurbishment and launch.

DSCOVR already had a plasma magnetometer bolted on that could measure the constant flow of atomic particles streaming away from the sun to measure the velocity, magnitude and direction of the solar wind’s magnetic field.

NOAA’s rejigged DSCOVR mission still has the Earth-viewing instruments originally slated to fly on Triana.

The Air Force signed on to the program to receive the space weather observations DSCOVR will produce. In exchange, the service paid SpaceX to launch the spacecraft.

The camera on DSCOVR — named EPIC — will not fulfill Gore’s call for uninterrupted live imagery of Earth. Restrictions on the data flow from the spacecraft to the ground will limit it to about six full-color images of the whole day side of the Earth every 24 hours, officials said.

Another instrument — NISTAR — will measure Earth’s energy budget, a data point that scientists say could tell how much human activity is contributing to climate change.

Gore issued a statement after DSCOVR’s launch Wednesday.

“It was inspiring to witness the launch of the Deep Space Climate Observatory,” Gore said. “DSCOVR has embarked on its mission to further our understanding of Earth and enable citizens and scientists alike to better understand the reality of the climate crisis and envision its solutions. DSCOVR will also give us a wonderful opportunity to see the beauty and fragility of our planet and, in doing so, remind us of the duty to protect our only home.”

The views of Earth should be available by July, after DSCOVR’s 110-day journey to the L1 location, where the observatory will conduct an insertion burn to enter a halo-like orbit around the Lagrange point.

DSCOVR is slated for a mission of at least two years, and it carries enough fuel to last five years.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.