SpaceX’s next launch of satellites for the company’s Starlink broadband network — planned in the final days of 2019 — will carry one spacecraft with an experimental coating designed to make it less reflective in orbit, a first step in assuaging concerns from scientists who say the deployment of thousands more Starlink stations would impede some astronomical observations.

Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer, told reporters Friday that the company wants to do “the right thing” and ensure the night sky remains accessible for scientific observations and inspiration.

SpaceX’s next Falcon 9 rocket launch dedicated to the Starlink network is scheduled in late December, roughly two weeks after the company launches the next Falcon 9 mission on its manifest. That mission, slated to carry a commercial geostationary telecom satellite, is planned for no earlier than Monday, Dec. 16.

The Starlink launch in late December will carry 60 new satellites to join 120 other Starlink data relay nodes launched on two previous missions in May and November.

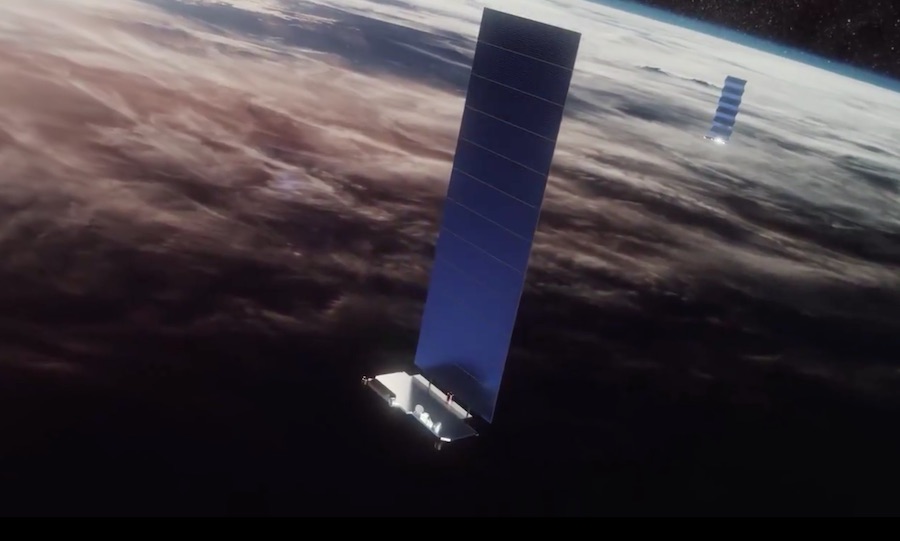

The Starlink satellites launched earlier this year traced paths across morning and evening twilight skies. The spacecraft were deployed from their Falcon 9 launchers in tight bunches, and were more reflective than expected, appearing to fly overhead in train-like formations before spreading out in the days and weeks after each launch.

Before spreading out and raising their orbits using ion thrusters, the Starlink satellites sometimes flared to become as luminous as the brightest stars in the sky. The flat-panel satellites are relatively small, with a deployable solar panel, and weigh around 573 pounds (260 kilograms) at launch, according to SpaceX.

Responding to astronomers’ protests, SpaceX said earlier this year it would take steps to make the bottom of each Starlink satellite less reflective. The 60 satellites launched in November did not have such a change, but one of the 60 spacecraft scheduled for launch in late December will have a modification to address the brightness concerns.

“This next batch has one satellite that we’ve put a coating on the bottom,” Shotwell said Friday in a meeting with reporters at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California. “This is going to be an experiment … We’re going to do trial and error to figure out what’s the best way to get this done. But we are going to get it done.”

Shotwell said the Starlink satellites for the late December launch have been delivered to Cape Canaveral from the Starlink factory in Redmond, Washington, for final launch preparations.

“Astronomy is one of a few things that gets little kids excited about space,” Shotwell said. “There are a lot of adults that get excited, too, who either depend on it for their living or for entertainment. But we want to make sure we do the right thing, to make sure little kids can look through their telescopes. It’d be cool for them to see a Starlink. I think that’s cool. But they should be looking at Saturn and the moon.”

Before committing to further satellite changes, Shotwell said SpaceX wants to make sure the coating works. SpaceX also wants to ensure the coating change does not adversely affect the performance of the satellite, such as its thermal properties.

“That’s why we can’t just say we’re just going to do this thing,” she said. “It also has to work.”

Shotwell said SpaceX was surprised that the Starlink satellites were so reflective after the first launch in May.

“There are lots of people that have looked at Starlink and looked at the satellites, lots of people knew what we were doing, and no one thought of this,” she said. “We didn’t think of it. The astronomy community didn’t think of it. It happened … Let’s go figure that out.”

SpaceX has approval from the Federal Communications Commission to launch and operate up to 12,000 Starlink satellites in the coming years. The company’s initial Starlink fleet will number 1,584 satellites to enable global Internet services, and SpaceX’s broadband network could approach that number of spacecraft with a series of up to two dozen Falcon 9/Starlink launches in 2020.

The American Astronomical Society has established a working group to connect the astronomical scientific community and SpaceX, the AAS said in a written update posted Dec. 5 on its website.

“The response from our community was loud enough that SpaceX reached out to the AAS looking to establish a line of communication,” wrote Kelsie Krafton, a publicly policy fellow at the American Astronomical Society. “Since optical/infrared interference doesn’t have a statutory or regulatory framework like radio interference, they hadn’t had any interactions with that part of our community.”

Krafton wrote that SpaceX and the AAS have discussed the Starlink brightness issue on eight telecons since June. The astronomy advocacy group says it has met with satellite industry representatives, congressional staff, federal officials and members of the space law community.

“Things are moving in a hopeful direction after our last two telecons,” Krafton wrote. “SpaceX is willing to test coatings to see if that helps bring down the brightness.”

Krafton wrote that astronomers are aiming to select a brightness level for SpaceX to target for their Starlink satellites. Simulations are also underway to model the Starlink satellites’ impacts to ground-based astronomical observatories, and astronomers have discussed the best way for SpaceX to disseminate their launch schedules to allow scientists to take measures to avoid observations that might be impacted by Starlink satellites, according to Krafton’s post on the AAS website.

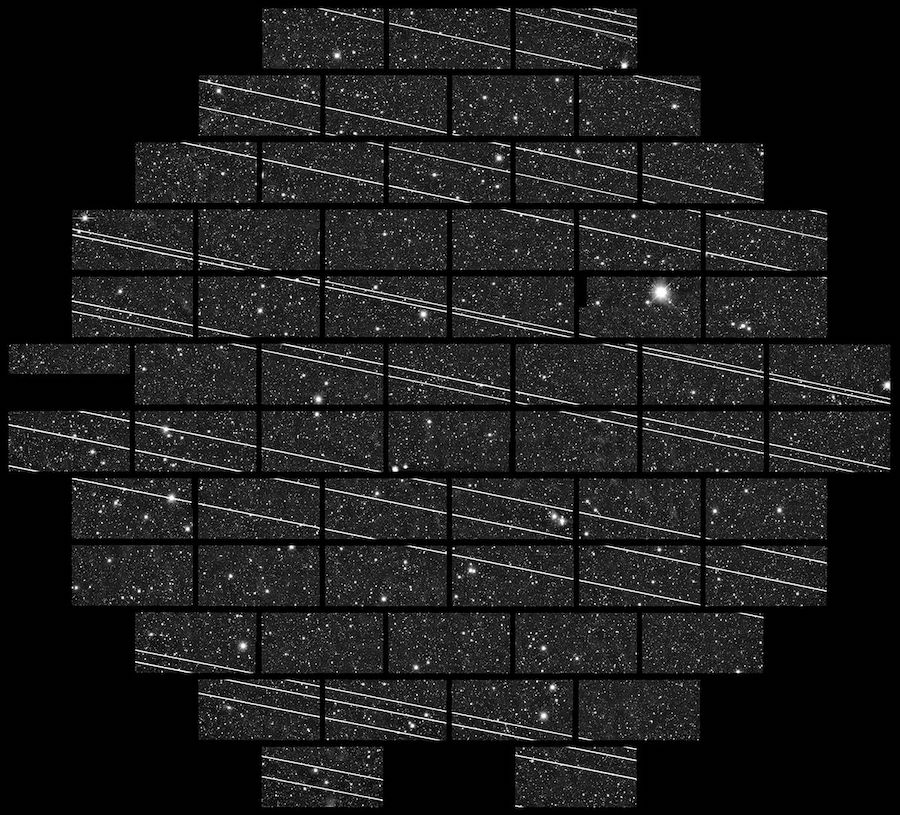

Astronomers want to make sure observations planned by the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, or LSST, remain unimpeded by satellite constellations planned by SpaceX, OneWeb, Amazon and other companies.

Funded by the U.S. government, the LSST is under construction in Chile and is designed to capture deep, wide-field images of the entire available sky, allowing astronomers to learn more about dark energy and dark matter, and detect potentially hazardous asteroids with orbits near Earth, among other objectives.

Members of the LSST science team said last month that, assuming the full deployment of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, nearly every exposure from the observatory within two hours of sunset or sunrise would have a satellite streak. During summer months, when twilight times longer, there could be a 40 percent impact on twilight observing time, according to the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, or AURA, which manages the LSST project for the National Science Foundation.

“Because of scattered light in the optics by the bright satellites, the scientific usefulness of an entire exposure can sometimes be negated,” AURA said in a statement last month. “Detection of near-Earth asteroids, normally surveyed for during twilight, would be particularly impacted. Dark energy surveys are also sensitive to the satellites because of streaks caused in the images. Avoiding saturation of streaks is vital.”

“The goal of Starlink is to provide worldwide internet service, an aspiration we do not want to impede, but this requires one to two orders of magnitude more low Earth orbiting satellites than currently exist,” Krafton wrote. “We do not want to give up access to optical observations from the ground. Our group’s task is to find a path forward that accommodates both uses of the sky.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.