Persistent problems with a seismometer instrument package will keep NASA’s InSight Mars lander from departing for the red planet during a March launch period, and officials said they will consider shelving the $675 million project if the issues prove too costly to fix.

The InSight spacecraft, a three-legged lander with instruments to study Mars’ interior structure, was supposed to launch in a 26-day window opening March 4.

Mars launch opportunities only come every 26 months, when the planets are in the right positions to make a direct journey possible.

“When you know you’re going to miss the window, it’s essentially game over, at least for this opportunity,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s science mission directorate.

“This is a case where the alignment of the planets matters, and in order to get from the Earth to Mars in the most efficient manner, they’re aligned about every 26 months,” Grunsfeld said Dec. 22. “So we’re looking at some time in the May 2018 timeframe for the next opportunity.”

But Grunsfeld did not rule out canceling the InSight mission.

“That is a question that’s on the table,” Grunsfeld said, adding that the delay in InSight’s launch from 2016 to 2018 automatically triggers a review on the future of the mission. NASA is also not sure how much the delay and repairs will cost, or whether it will bust the mission’s cost cap.

NASA has spent about $525 million on InSight to date, according to Jim Green, director of NASA’s planetary science division.

Engineers shipped the lander and its interplanetary carrier craft from a Lockheed Martin factory near Denver to Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on Dec. 16, but the spacecraft went to its launch site without one of its two main science instruments.

Managers hoped to bolt the seismometer to the InSight lander at Vandenberg in the weeks before liftoff, and launch preparations continued to support the March launch period, with the first stage of InSight’s Atlas 5 rocket already hoisted on its launch pad in mid-December.

The spacecraft will now be returned to Lockheed Martin’s satellite integration center in Colorado for storage until NASA decides what to do with the InSight mission.

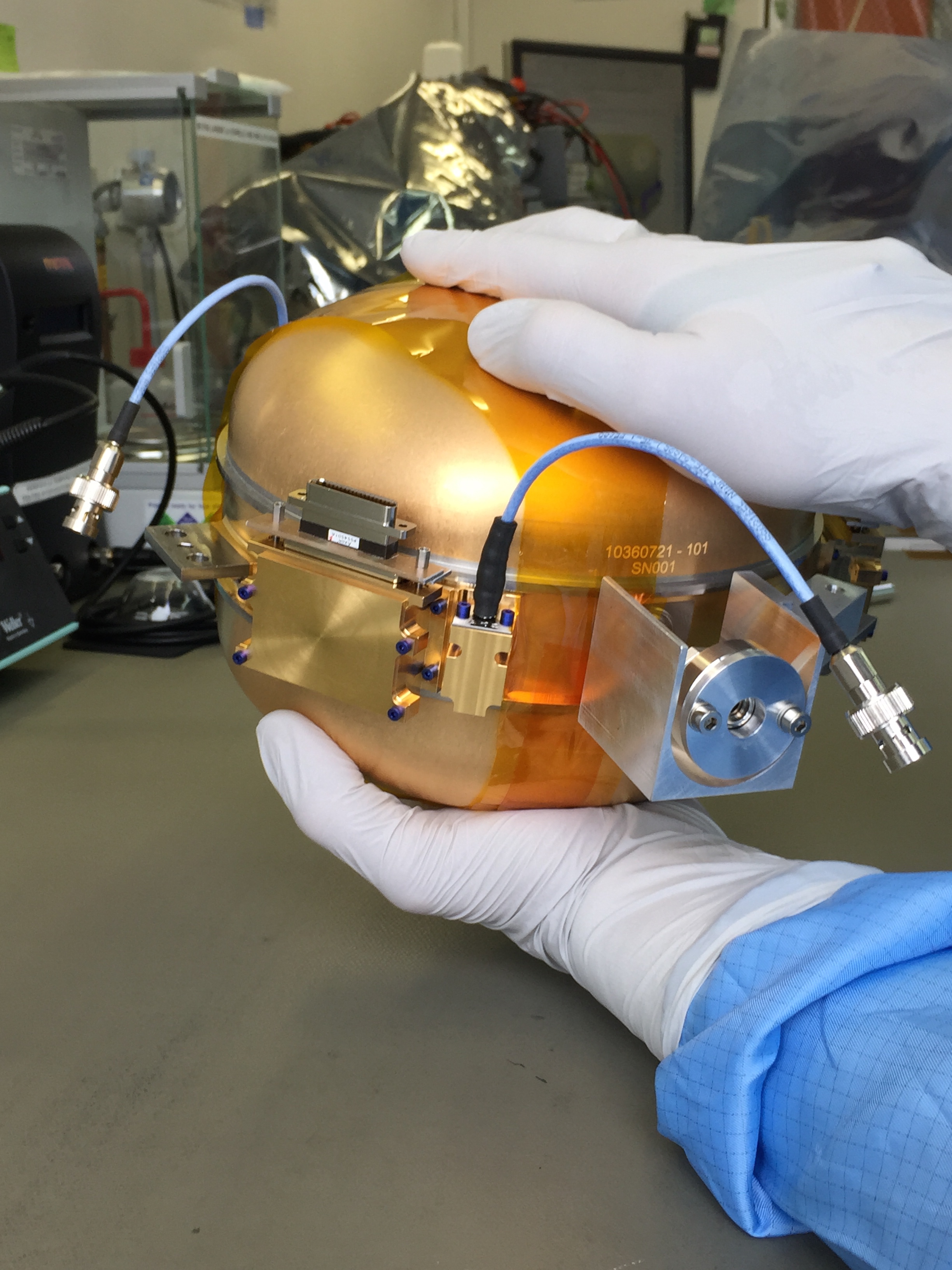

InSight’s French-developed seismometer package ran into trouble in August with its spherical vacuum chamber, which measures about the size of a volleyball. The container holds three seismic sensors, and it must be pumped down to a vacuum on Mars to obtain the sensitive measurements required to detect light tremors scientists believe still occasionally occur on the red planet, despite its waning geologic activity.

Technicians have had trouble sealing the vacuum sphere to keep air from encroaching inside the container and spoiling InSight’s seismic measurements.

“The original problem we had actually was a leak through an electrical connector,” said Bruce Banerdt, the InSight mission’s principal investigator from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a Dec. 16 interview with Spaceflight Now. “We had to bring the electrical wires from inside the vacuum sphere and out to the electronics, and there’s one of these feed-throughs that developed some leaks. That’s what we had our original problem with. We fixed that, we sort of encapsulated that connector, and we’ve had trouble since then with the sealing off of the sphere itself.”

A last-ditch effort to seal the enclosure last week did not hold up to pressure during a thermal vacuum test at a facility in Paris designed to check its resilience against the extreme conditions on Mars, NASA officials said Dec. 22.

“It was during the cold cycle testing, just within the last few days, that we have determined that the sphere is still leaking,” Grunsfeld said. “We’re close enough to launch that unfortunately we don’t have enough time to try and identify the leak, fix it, and recover, and still make it to the launch pad in March, and we’re also wondering is it something inherent to the design? Is it some other issue that we haven’t identified? I think, in some sense, we don’t have a decision to make because we’re not ready to go.”

Banerdt said the seismometer’s spherical container was to be pumped down to a billionth of the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere, but the seismic sensors inside the sphere could still collect data as long as it remained below a ten-thousandth of Earth’s air pressure.

At the leak rate observed earlier this month, the pressure inside the sphere would reach twice that level within a few days, rendering the instrument useless, officials said.

“At this leak rate, it would not work at all,” Grunsfeld said.

Marc Pircher, director of the French space agency — CNES — center in Toulouse, said the latest leak was the fourth detected on the InSight seismic sphere. Each time technicians fixed one leak, another one appeared, he said.

“It was a very small leak, and we tried to solve it, but unfortunately, and we apologize for that, we had the disappointment to see that we did not solve the last one,” Pircher said. “We have to fix it, and we did not have time to do it before the launch.”

NASA chose InSight from a competition with dozens of proposed interplanetary probes in 2012, beating out co-finalists that would have sent a floating science platform to a hydrocarbon lake on Saturn’s moon Titan or launched a spacecraft to hop around the surface of a comet. InSight was the 12th mission selected in NASA’s Discovery program, a series of cost-constrained solar system missions with focused science objectives.

InSight’s rocket-assisted landing craft is based on the Mars Phoenix lander that successfully reached the red planet in 2008, but scientists outfitted the probe with new science instruments.

A heat probe provided by Germany will burrow more than 16 feet — about 5 meters — into the Martian crust to measure how much heat is escaping the red planet’s interior. The seismometer instrument from France will register Martian quakes, which have not been detected to date but scientists believe occur.

A third science investigation aboard InSight will glean information about the planet’s wobble by analyzing radio signals transmitted between Earth and Mars.

The spacecraft, rocket and other components of InSight’s payload were ready to go, but the seismometer’s design, which requires an airless vacuum around its sensors, proved difficult.

“Essentially, a seismometer is a mass that stays still, inertially still, as it’s attached to the ground, so any air resistance between that pendulum creates damping which is then translated into noise,” Banerdt told Spaceflight Now in an interview days before NASA’s decision to delay InSight’s launch.

Once InSight reaches its landing site, a flat Martian equatorial plain named Elysium Planitia, a robotic arm will deploy the underground heat probe and seismometer directly on the Martian soil.

“We’re making extremely fine measurements, down to the sub-atomic level of displacement, and so in order to eliminate the air damping below the levels that we require, we have to have the pressure inside the sphere around those sensors at about a tenth of a millibar,” Banerdt said.

Despite the consequence of cancellation looming over the InSight mission, officials said they were confident the seismometer could be flight-ready in time for the May 2018 launch opportunity.

“It’s a question of months,” Pircher said. “It’s not a question of days, it’s not a question of weeks, it’s a question of a few months in order to be sure that we have the right qualification of the sphere and the right sphere. The sensors themselves are very, very good, so we do not need to change them. We need to make sure they are well-packaged.”

“I don’t think anybody has a question that with 26 months that we would not, in principle, be able to solve the problem, even if it involves a redesign of the enclosure around the seismometers,” Grunsfeld said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.