With a Falcon 9 rocket launch Friday, SpaceX added 57 more satellites to the Starlink broadband fleet and deployed a pair of piggyback commercial Earth-imaging reconnaissance satellites for BlackSky, wrapping up a busy week that began with SpaceX’s return of two NASA astronauts to Earth and the first low-altitude test flight of the company’s next-generation Starship vehicle.

The 59 commercial satellites took off at 1:12:05 a.m. EDT (0512:05 GMT) on top of a Falcon 9 rocket from pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Nine Merlin 1D engines flashed to life with a deep rumble to hurl the 229-foot-tall (70-meter) rocket into the sky with 1.7 million pound of thrust. After pitching to align with a trajectory toward the northeast from Florida’s Space Coast, the Falcon 9 soared into the stratosphere trailing a brilliant orange exhaust plume before shutting down its first stage engines two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff.

Seconds later, the first stage booster dropped away from the Falcon 9’s second stage to begin a guided descent toward SpaceX’s drone ship parked in the Atlantic Ocean northeast of Cape Canaveral.

The Merlin engine on the second stage ignited two times to maneuver the Starlink and BlackSky satellites to a near-circular orbit nearly 250 miles (400 kilometers) above Earth. Meanwhile, the Falcon 9’s first stage booster flew to a propulsive landing on SpaceX’s rocket recovery vessel, a football field-sized platform positioned nearly 400 miles (around 630 kilometers) downrange from the Kennedy Space Center.

Two BlackSky Earth-imaging satellites, each with a mass of about 121 pounds (55 kilograms), deployed from the top of the stack of Starlink spacecraft more than an hour into the mission. BlackSky booked the launch for its satellites through Spaceflight, a Seattle-based rideshare broker, utilizing room in the Falcon 9 rocket’s payload compartment made available by SpaceX.

Read our earlier story for background on BlackSky and SpaceX’s rideshare launch service offering.

BlackSky is deploying a fleet of Earth observation satellites designed to monitor changes across Earth’s surface, feeding near real-time geospatial intelligence data to governments and corporate clients. The two microsatellites on Friday’s mission are designated Global 7 and Global 8, but they are actually the fifth and sixth operational satellites in the BlackSky fleet, which the company could eventually number more than 50 satellites, depending on customer demand.

The BlackSky satellites were built by LeoStella, a joint venture between Spaceflight Industries and Thales Alenia Space, a major European satellite manufacturer. LeoStella’s production facility is located in Tukwila, Washington, a suburb of Seattle.

The satellites have electrothermal propulsion systems that use water as a propellant. Each of the current generation of BlackSky Global spacecraft can capture up to 1,000 color images per day, with a resolution of about 3 feet (1 meter).

With the piggyback payloads away, the Falcon 9’s upper stage spun up for release of the 57 Starlink satellites at 2:45 a.m. EDT (0645 GMT). Live video beamed back to Earth from the Falcon 9 rocket showed the flat-panel satellites flying free of the upper stage as they soared nearly 250 miles over the Pacific Ocean near Baja California.

All 57 Starlink broadband satellites launched this morning from the Kennedy Space Center have successfully separated from their Falcon 9 rocket in orbit.

This brings the total number of Starlinks launched since May 2019 to 595 satellites. https://t.co/T8cU2Vl2bf pic.twitter.com/xp8EJwD69d

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) August 7, 2020

SpaceX declared success, concluding the 90th flight of a Falcon 9 rocket since 2010, and the 13th Falcon 9 launch of the year. It was also the 57th time SpaceX has recovered a reusable Falcon first stage booster, and it marked the fifth flight of the booster designated B1051.

The launch early Friday came less than five days after the return of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft to Earth with NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, completing the ship’s first mission with crew members on-board. The test flight sets the stage for NASA’s certification of the Crew Dragon for regular crew rotation flights to the International Space Station.

On Tuesday, SpaceX performed a low-altitude “hop” test of a prototype of the company’s next-generation Starship space transportation vehicle.

SpaceX’s Starlink network is designed to provide low-latency, high-speed Internet service around the world. With Friday’s mission, SpaceX has launched 595 flat-panel Starlink spacecraft since beginning full-scale deployment of the orbital network in May 2019, making the company the owner of the world’s largest fleet of satellites.

Each of the flat-panel satellites weighs about a quarter-ton, and are built by SpaceX in Redmond, Washington. Once in orbit, they will deploy solar panels to begin producing electricity, then activate their krypton ion thrusters to raise their altitude to around 341 miles, or 550 kilometers.

SpaceX says it needs 24 launches to provide Starlink Internet coverage over nearly all of the populated world, and 12 launches could enable coverage of higher latitude regions, such as Canada and the northern United States.

The launch Friday will be the 10th mission to carry Starlink satellites into orbit, but the Starlink spacecraft deployed on the network’s first dedicated launch were designed to demonstrate satellite and payload performance. SpaceX has not said if any of those satellites might be incorporated into the operational fleet.

The Falcon 9 rocket can loft up to 60 Starlink satellites — each weighing about a quarter-ton — on a single Falcon 9 launch. But launches with secondary payloads, such as BlackSky’s new Earth-imaging satellites, can carry fewer Starlinks to allow the rideshare passengers room to fit on the rocket.

The initial phase of the Starlink network will number 1,584 satellites, according to SpaceX’s regulatory filings with the Federal Communications Commission. But SpaceX plans launch thousands more satellites, depending on market demand, and the company has regulatory approval from the FCC to operate up to 12,000 Starlink relay nodes in low Earth orbit.

Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, says the Starlink network could earn revenue to fund the company’s ambition for interplanetary space travel, and eventually establish a human settlement on Mars.

SpaceX fans sleuthing through coding on the Starlink website last month found images of a prototype version of the antenna consumers will use to connect to the Internet network.

UFO on a stick aka Starlink user terminal looks beautiful pic.twitter.com/1aog0FS1jq

— Viv 🐉 (@flcnhvy) July 14, 2020

Musk responded to the tweet, writing the the Starlink ground terminal “has motors to self-orient for optimal view angle. No expert installer required.”

SpaceX has not released pricing information for the Starlink service.

SpaceX says it will soon begin “beta testing” using the Starlink network. The company is collecting email information and mailing addresses from prospective customers, and SpaceX says it will provide updates on Starlink news and service availability to those who sign up.

The beta testing is expected to begin for users living at higher latitudes — such as the northern United States and southern Canada — where the partially-complete Starlink satellite fleet can provide more consistent service. SpaceX will send a Starlink kit including a small antenna, router and other equipment to people selected for beta testing.

Astronomers have raised concerns about the brightness of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, and other companies that plan to launch large numbers of broadband satellites into low Earth orbit.

The Starlink satellites are brighter than expected, and are visible in trains soon after each launch, before spreading out and dimming as they travel higher above Earth.

SpaceX introduced a darker coating on a Starlink satellite launched in January in a bid to reduce the amount of sunlight the spacecraft reflects down to Earth. That offered some improvement, but not enough for ultra-sensitive observatories like the U.S government-funded Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, which will collect all-sky images to study distant galaxies, stars, and search for potentially dangerous asteroids close to Earth.

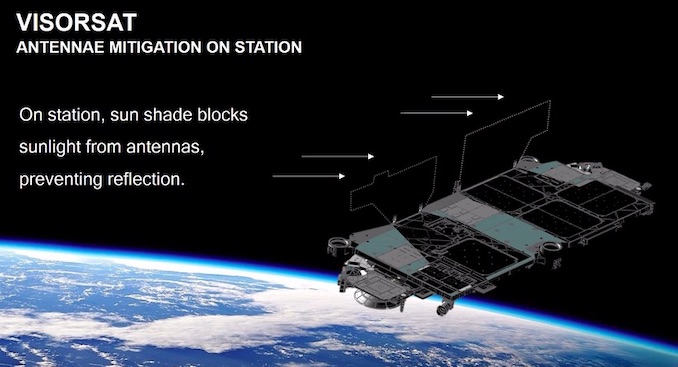

SpaceX launched a satellite June 3 with a new unfolding radio-transparent sunshade to block sunlight from reaching bright surfaces on the spacecraft, such as its antennas. SpaceX says all Starlink satellites beginning with the spacecraft launched Friday will carry the sunshades.

Coupled with changes in how the satellites are oriented when they are at lower altitudes soon after launch, the sun visors could alleviate the most serious impacts on astronomy from the Starlink network, and eliminate the Starlink satellites from naked eye vision once they reach their 341-mile-high operational orbit.

The Vera Rubin Observatory’s 3,200-megapixel camera will start astronomical surveys in 2022. Each image will cover a region of the sky the size of 40 full moons, and many of the images will include light streaks left by satellites from the Starlink network, and potentially other satellite constellations.

The worst impacts will come after dusk and before dawn. That’s a time of day when astronomers want to search for asteroids.

Astronomers on the Vera Rubin Observatory team say SpaceX has been working with them since last year to try to reduce the impacts of the Starlink network on their scientific program. Astronomers illuminated a Vera Rubin imaging detector in a test to see how it would respond to the passage of a satellite as bright as a Starlink. They found the satellite leaves behind not just a single trail, but “ghost” trails away from the spacecraft’s path.

Scientists from Vera Rubin Observatory said the ghost artifacts could be removed with software if the Starlink satellites are dimmer than 7th magnitude. Observations of the Starlink spacecraft with the darker coating indicate that change dimmed the satellite to about 6.1 magnitude, somewhat shy of Vera Rubin’s requirement.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.