EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated May 25 with final loss of crew and loss of mission risk numbers from NASA.

After a two-day readiness review, NASA managers gave a green light Friday for SpaceX to proceed with final preparations for launch next Wednesday, May 27, of a commercial spaceship carrying astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken to the International Space Station on the first orbital spaceflight from U.S. soil since 2011.

Hours later, SpaceX test-fired the 215-foot-tall (65-meter) Falcon 9 rocket that will boost Hurley and Behnken into orbit aboard the company’s Crew Dragon spacecraft.

The Flight Readiness Review’s conclusion Friday kicked off a busy Memorial Day weekend at the Kennedy Space Center. The Dragon astronauts will put on in their SpaceX-made flight suits Saturday and ride in a Tesla Model X automobile to launch pad 39A, where the Falcon 9 and Crew Dragon capsule were placed on their seaside launch mount Thursday.

Hurley and Behnken — both veterans of two space shuttle flights — will climb aboard the Dragon capsule with the help of about a half-dozen SpaceX crew technicians, practicing the steps they will take on launch day.

On Monday, SpaceX will convene a Launch Readiness Review to go over data and results from the test-firing Friday and the crew dress rehearsal Saturday. If all looks good, preparations will proceed toward launch of the first orbital crewed mission from the Kennedy Space Center in nearly nine years at 4:33 p.m. EDT (2033 GMT) Wednesday.

Assuming the mission takes off Wednesday, the Crew Dragon is scheduled to glide to an automated docking with the International Space Station around 11:40 a.m. EDT (1540 GMT) Thursday. Hurley and Behnken are slated to spend one-to-four months on the orbiting research outpost before coming back to Earth for a parachute-assisted splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean.

The Flight Readiness Review began Thursday and ran into overtime Friday. NASA officials anticipated ahead of time that might happen, given the volume of data to discuss for the first crewed flight on a brand new spacecraft design.

“We had a very successful Flight Readiness Review, in that we did thorough review of all fo the systems and all the risks,” said Steve Jurczyk, NASA’s associate administrator, who chaired the review meeting. “And it was unanimous on the board that we are go for launch.

“It is really exciting to be launching American astronauts on American rockets from American soil — from Kennedy Space Center — for the first time in nine years,” Jurczyk said in a press conference Friday. “I know it’s been a long, really challenging road, and I just cannot say how proud I am of the NASA-SpaceX team for all their talent, hard work, dedication and perseverance to get to this point of five days from launch.”

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine confirms the Flight Readiness Review resulted in a GO to proceed toward a May 27 launch date for the Crew Dragon test flight, the first crewed orbital mission from US soil since 2011. https://t.co/Y9pANccivZ pic.twitter.com/sEAaNdz4FM

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) May 22, 2020

“Today, we got a go to launch, but really it’s a go for the mission,” said Benji Reed, SpaceX’s director of crew mission management. “There will be lots more data, lots more reviews in the next few days. There will be constant vigilance and watching of the data and observations. As we go through the mission, there will be other reviews and conversations to make sure we’re go for each aspect, including go to come home.”

NASA managers received briefings from agency and SpaceX engineers during the Flight Readiness Review, including presentations on topics that garnered widespread attention over the last year, such as the Crew Dragon’s parachutes and an abort propulsion system problem that led to the explosion of a capsule during a ground test in April 2019.

“We established a little while ago that the original chute design did not have adequate margin, based on some knowledge we had gained through testing of how the chutes deploy, and the loading on the chutes,” Jurczyk said. “So SpaceX stepped up and did a new chute design, and we had to qualify that new chute design to higher margins than we had the previous chutes.

“The NASA-SpaceX team did an amazing job laying out a test program and executing that test program,” Jurczyk said. “However, it’s fewer tests than we normally would see on a parachute qualification program. So we took a long time in a couple of presentations during the review to have the team walk us through the design, the changes, the qualification testing, and the margins on the chute to make sure that everybody was good with how those chutes were qualified. And we had very high confidence that they will function as we need them to when Bob and Doug return from the International Space Station.”

The Crew Dragon uses a series of pilot and drogue chutes during descent, then unfurls four main parachutes to brake for splashdown. At the end of a typical mission, the Crew Dragon spacecraft will splash down in the Atlantic Ocean around 24 nautical miles off the coast of Cape Canaveral.

The capsule’s abort system was also a topic of extended discussion during the Flight Readiness Review. In the event of a major problem during fueling of the Falcon 9 rocket, or a launch failure during the vehicle’s climb into orbit, the Crew Dragon can fire eight SuperDraco engines to push the capsule off the launch vehicle and propel the astronauts to safety.

The SuperDracos consume a high-pressure mix of hydrazine fuel and nitrogen tetroxide oxidizer. A Dragon spacecraft that completed an unpiloted test flight to the space station in March 2019 was destroyed during a ground test-firing of the SuperDraco engines last April at Cape Canaveral.

Investigators traced the cause of the explosion to a leaky valve inside the capsule’s high-pressure abort propulsion system. The leak allowed nitrogen tetroxide to leak into the propulsion system’s helium pressurization lines, which are designed to rapidly prime the SuperDraco thrusters to fire up in quick response to a launch emergency.

As the pressurization system activated during the ground test last year, a slug of nitrogen tetroxide was forced back into the faulty titanium valve, triggering an explosion. Experts spent months studying the physics of the accident, and learned new information about how titanium components used in aerospace vehicles might ignite under certain conditions.

SpaceX replaced the suspect valve in future Crew Dragon spacecraft with a single-use burst disk designed to rupture during activation of the SuperDraco abort thrusters, which would only occur during a launch failure.

The fix was tested during a second ground firing in November, then again during a high-altitude launch escape test in January over the Atlantic Ocean.

Between the parachutes, the destroyed capsule and the impacts of a global pandemic, getting to SpaceX’s first crewed mission proved a challenge.

“Last April, I probably wasn’t thinking I was going to be flying (crew) in a year, but you can never sell this NASA and SpaceX team short,” said Kathy Lueders, managers of NASA’s commercial crew program. “They have always accomplished miracles for me, and I’m very, very proud of them right now.”

Jurczyk said NASA officials also discussed a recent “performance shortfall” during a test of the Crew Dragon’s internal fire suppression system.

“That’s a system tat suppresses any fire or any equipment underneath the floor of Dragon,” Jurczyk said. “The team … analyzed both the hazards there, as well as the ability to suppress a fire, and we’ve deemed the risk to be very low there.”

Jurczyk took the place of Doug Loverro, the former head of NASA’s human spaceflight directorate, for this week’s Flight Readiness Review. Loverro, who was due to chair the FRR, abruptly resigned effective Monday, May 18.

In a letter to NASA employees, Loverro wrote that he resigned due to a “mistake” he made earlier this year. Multiple sources said Loverro violated a procurement rule during a competition to select contractors for NASA’s Human Landing System for the Artemis program, which aims to develop crewed moon landing vehicles to carry astronauts to the lunar surface.

Jurczyk, NASA’s most senior career civil servant, stepped into the role as chair of the Flight Readiness Review.

The Crew Dragon’s debut flight with astronauts has been nearly a decade in the making. NASA first awarded SpaceX funding to work on a human-rated spacecraft in 2011.

Funded and led by billionaire Elon Musk, SpaceX has won a series of NASA contracts and funding agreements over the last nine years for work on the Crew Dragon project. To date, NASA has agreed to pay SpaceX more than $3.1 billion to develop the Crew Dragon, and then fly at least six operational crew rotation missions to the space station.

NASA also awarded Boeing a similar series of contracts for development and flights of the Starliner crew capsule. The Starliner’s first test mission without a crew ended prematurely in December without reaching the space station, and Boeing will re-fly the unpiloted demonstration mission later this year before the Starliner is cleared for its first launch with astronauts.

The first operational Crew Dragon flight will follow the test flight set for launch next week, which is officially designated Demo-2, or DM-2. It follows the first Crew Dragon test flight to the space station last year, which did not carry any astronauts on-board.

SpaceX has also completed two major tests of the Crew Dragon’s launch abort system — a pad abort in 2015 and the in-flight escape demonstration in January.

According to Jurczyk, this week’s FRR doubled as an “interim human-rating certification review” for SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft.

“What I mean by interim is that we’ve validated that this system meets the human-rating certification requirements for the Demo-2 mission, and those requirements feed forward to future missions, including the Crew-1 mission (the Dragon’s first operational crew rotation flight),” Jurczyk said. “We will have a final human-rating certification review after Demo-2 and before the Crew-1 mission, just to certify the relatively small set of design changes between the Demo-2 system and the Crew-1 system. And at that point, we’ll deem the system human-rating certified.”

NASA also determined the Crew Dragon meets the agency’s risk requirements for the commercial crew program. When NASA established requirements for the new commercial crew spaceships, agency officials set the program’s safety threshold at 1-in-270 odds of an accident during a 210-day mission that would kill the astronauts on-board.

Lueders said Friday that SpaceX meets that risk requirement.

Josh Finch, a NASA spokesperson, told Spaceflight Now that the agency’s calculated “Loss Of Crew” probability for SpaceX’s Demo-2 test flight is 1-in-276, exceeding the commercial crew program’s requirement threshold of 1-in-270.

In response to a question from Spaceflight Now, Finch said the 1-in-276 number includes mitigations to reduce the risk, such as on-orbit inspections of the Crew Dragon spacecraft once it’s docked at the space station to look for damage from micrometeoroids and orbital debris, or MMOD.

Collisions with tiny fragments of space junk or naturally-occurring dust grains or pebble-sized rock fragments could damage the ship’s heat shield.

NASA pegs the overall risk of a Loss Of Mission is 1-in-60. That risk covers scenarios where the Crew Dragon doesn’t reach the space station as planned, but the crew safely returns to Earth.

But determining the loss of crew, or LOC, probability for any given flight is tricky. The number hinges on a number of factors, including numerical and statistical inputs, many of which are grounded in assumptions.

Bill Gerstenmaier, who led NASA’s human spaceflight programs from 2005 until last year, said in 2017 that at the time of the first space shuttle flight in 1981, engineers calculated the probability of a loss of crew on that mission between 1-in-500 and 1-in-5,000. After grounding the loss of crew model with flight data from shuttle missions, NASA determined the first space shuttle flight actually had a 1-in-12 chance of ending with the loss of the crew, Gerstenmaier said.

By the end of the shuttle program, after two fatal disasters, NASA calculated the risk of a loss-of-crew on any single mission was about 1-in-90.

In retrospect, NASA calculated the “loss of crew” probability at 1-in-12 for the first space shuttle mission in April 1981, which ended successfully.

READ MORE: https://t.co/XSDTP1wr7w pic.twitter.com/FjdMB3dLY2

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) May 25, 2020

SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spaceship has the ability to escape its Falcon 9 launch vehicle throughout the ascent sequence into orbit, a capability not available for space shuttle crews.

Regardless of the imprecise nature of such loss-of-crew probabilities, officials agree that a test flight of a new spacecraft is risky.

“Right now, we are trying to identify any risk that we know of that’s out there, and continue to look at risks and buy them down,” Lueders said. “But we also cant fool ourselves. Human spaceflight is really, really tough, and it’s why we continue to look for risks and do additional assessments. We never feel comfortable because that’s when you’re not searching.

“Our teams are scouring and thinking of every single risk that’s out there, and we’ve worked our butt off to buy down the ones we know of,” she said. “And we’ll continue to look and continue to buy them down until we bring them (Hurley and Behnken) home.”

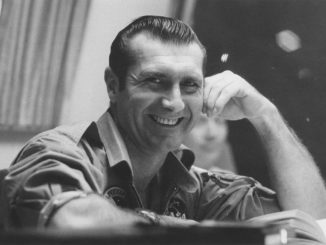

NASA astronaut Bob Behnken, the Crew Dragon’s Demo-2 joint operations commander, discusses his view on the risk of the upcoming test flight to the International Space Station. https://t.co/Y9pANccivZ pic.twitter.com/49Q3VeYSFS

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) May 22, 2020

In their final pre-launch press conference Friday, the Dragon astronauts said they were comfortable with the risk.

“We’ve had the luxury over the last five-plus years to be deeply embedded and understanding the trades that were made,” said Behnken, the Demo-2 mission’s joint operations commander. “There are often cases where a hardware change can be implemented, or there can be an operational change that reduces that risk, or manages it in some way.

“I think we’re really comfortable with it, and we think that those trades have been made appropriately,” he said. “As far as insight goes, we’ve had probably more than any crew has (had) in recent history.”

In addition to the tests of the Crew Dragon spacecraft itself, SpaceX has launched 84 Falcon 9 rocket missions since the first version of the launcher debuted June 4, 2010. Eighty-three of the flights successfully reached orbit.

A Falcon 9 rocket also exploded during the final minutes before a ground test-firing at Cape Canaveral in September 2016. SpaceX said that failure was caused when a helium pressurant tank suddenly ruptured on the Falcon 9’s second stage.

SpaceX says the Crew Dragon’s escape engines would have activated to save the astronauts if such an accident occurred before a launch with a crew.

After introducing design fixes, SpaceX has logged 59 straight successful launches using Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets.

“It wasn’t a long history (on the Falcon 9) when we started this program, but it has panned out to have quite a number of flights under its belt, and its evolution has become more and more safe as it’s been operated,” Behnken said. “Thats something that we really do appreciate. It’s remarkable to see all the other missions that have contributed to the human spaceflight program by being, in some sense, a test mission for us before we have a chance to fly on the Falcon 9.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.