An unpiloted demonstration flight of Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule ended prematurely Sunday with a smooth airbag-cushioned predawn landing in New Mexico after a timing glitch prevented it from docking with the International Space Station, leaving some test objectives incomplete as NASA begins analyzing data to determine if astronauts should fly on the next Starliner mission.

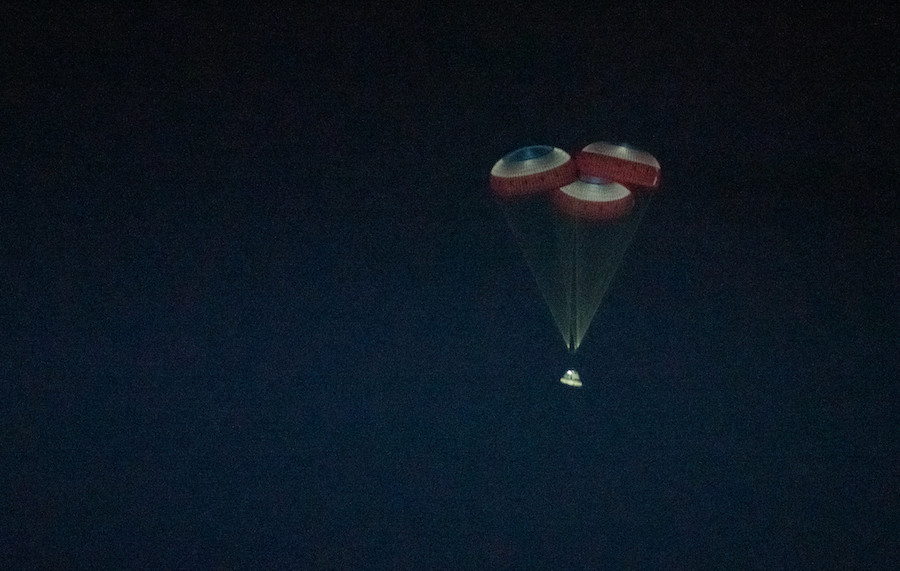

Concluding its first trip into space, the reusable Starliner capsule touched down at White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico at 7:58 a.m. EST (5:58 a.m. MST; 1258 GMT) Sunday. Three red, white and blue parachutes slowed the ship’s descent, and six airbags inflated to soften the spacecraft’s landing on the desert floor, marking the first time a U.S. human-rated capsule has returned from orbit to touch down on solid ground.

Boeing recovery forces quickly approached the spaceship, ensured it was safe and stable, installed a protective environmental enclosure and opened the capsule’s hatch about an hour after landing, practicing procedures they will perform to help astronauts disembark on future missions.

The Starliner’s landing Sunday appeared to go almost perfectly, hitting a “bullseye” in the landing zone in New Mexico after an inauspicious start to the test flight Friday.

“The vessel looks great,” said Jim Chilton, vice president of Boeing’s space and launch division. “The ground crews, they’re telling us there’s hardly any charring, (it’s) perfectly level on the airbags, and that bodes very well for reusability.”

The capsule started its flight with an 11-hour error in its mission elapsed timer setting, triggering a cascading series of problems that led to the Starliner burning too much fuel to reach the space station and deliver cargo.

Nevertheless, NASA and Boeing officials presented a positive message after Sunday’s landing, suggesting the Starliner program could move forward after a partially successful test flight. Depending on the outcome of a comprehensive data review, NASA could clear astronauts to fly on the next Starliner mission as originally intended, officials said.

“If you went straight down the checklist, I think we’d be in the low 60 percent (range) right now (of mission objectives accomplished),” Chilton said Sunday. “Inside the capsule, we have a series of data recorders, and the data on those recorders is not sent back home through telemetry — things like temperature sensors on the hull and strain gauges to see bending and what kind of shock did you see.”

Boeing’s engineers will not get the results of some of the measurements until the spacecraft is transported back to the Starliner factory and refurbishment facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. That is expected to take up to two weeks.

“If I was going to infer how that data was going to come out — from cabin temperatures and how pristine the vehicle looks — I’d say we’re probably about in the 85 to 90 percent range of our (accomplished) test objectives,” Chilton said.

Chilton added the data review is not expected to be complete until “well into January.”

With the Starliner spacecraft safely back on Earth, NASA and Boeing managers will review the mission results and determine whether the capsule performed well enough to permit Boeing test pilot Chris Ferguson and NASA astronauts Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann to fly on the next Starliner mission in 2020.

“In terms of looking ahead to the Crew Flight Test, I think we have to take a little bit of time to look through all the data and see how the vehicle performed in all phases — orbit, entry and ascent — and we’ll go look at that and we’ll look the objectives we did not get, which were the rendezvous, approach and docking,” said Steve Stich, deputy manager of NASA’s commercial crew program. “And we’ll have to sit down and talk about what we do for the Crew Flight Test.

“To me, there’s good data out there that once we go through it, maybe it’s acceptable to go to the next step and do the Crew Flight Test,” Stich said.

Another option available to NASA is to redo the Starliner’s unpiloted test flight, a decision that would likely cost hundreds of millions of dollars and delay the program by months, if not longer.

Through a series of agreements and contracts since 2010, NASA is paying Boeing at least $4.8 billion to develop, demonstrate and fly the Starliner spacecraft for NASA astronauts traveling to the space station. SpaceX has received a similar set of contracts from NASA valued at $3.1 billion for the company’s Crew Dragon capsule, giving the U.S. space agency two independent ways of ferrying crews to and from the space station and ending NASA’s reliance on Russia for astronaut transportation.

But the multibillion-dollar government contracts are for commercial services, and Boeing and SpaceX retain ownership of the spacecraft, oversee flight operations and control access to proprietary data.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said Sunday that he is optimistic the agency’s commercial crew program can “move forward” with the Starliner program despite the spacecraft’s failure to dock with the space station on the unpiloted Orbital Flight Test.

“Yes, there are elements of this that are missing, but there are a whole lot of elements that were completed in a positive and meaningful way,” he said. “Given what we know today, we know that we are going to move forward. We know that we’ve got a lot of learning in front of us. We’ve got enough information and data to keep moving forward in a positive way.”

The mission elapsed timer issue that cut short Starliner’s planned eight-day mission started before the spacecraft lifted off Friday from Cape Canaveral aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, according to Chilton.

“Our spacecraft needs to reach down into the Atlas 5 and figure out what time it is, where the Atlas 5 is in its mission profile, and then we set the clock based on that,” Chilton said in a press conference Saturday. “Somehow we reached in there and grabbed the wrong (number). This doesn’t look like an Atlas problem. This looks like we reached in and grabbed the wrong coefficient.”

“As a result of starting the clock at the wrong time, the spacecraft upon reaching space, she thought she was later in the mission, and, being autonomous, started to behave that way,” Chilton said. “And so it wasn’t in the orbit we expected without the burn and it wasn’t in the attitude expected and was, in fact, adjusting that attitude.”

The frenetic thruster firings began almost as soon as the Starliner separated from the Atlas 5 rocket’s Centaur upper stage, which intentionally flew on a flattened, suborbital trajectory designed to reduce g-force loads on astronaut crews during a launch abort scenario.

The timing error prevented the Starliner from accomplishing its targeted orbit insertion maneuver. Mission control uplinked commands for the spacecraft to perform a series of burns with its smaller thrusters to reach a stable, but unplanned orbit, but the ship was no longer in a position to reach the space station.

The continual burns caused the thrusters to get hot, and in one case, a set of thrusters depleted its propellant supply. Despite intermittent messages suggesting some of the Starliner’s 28 service module control jets were unavailable, ground controllers were able to recover and reactivate all but one of the thrusters before re-entry, officials said.

“The mission elapsed timing error did absolutely result in a number of follow-on challenges,” Bridenstine said Saturday. “The spacecraft thought it was in a position it was not in, so it was trying to get in the right position. So the engines were firing, the reaction control was trying to put the spacecraft in the right position.

“And that resulted in some of these engines exceeding their limitations, both from a temperature perspective and from a duty cycle (perspective),” Bridenstine said. “The engines are only supposed to run a certain number of times in a certain amount of time, and those were exceeded. Had the mission elapsed timing been correct, none of that would have happened.”

Stich said Sunday that the toughest part of the Starliner test flight was the spacecraft’s return to Earth Sunday.

“The No. 1 flight test objective was a successful de-orbit, re-entry and landing, and we did that today,” Stich said. “The vehicle flew phenomenally during entry. All the maneuvers were just exactly as planned.”

After giving up on test flight’s planned rendezvous with the space station, mission managers focused on conducting as many demonstrations of the Starliner spacecraft as possible during an abbreviated two-day solo flight in low Earth orbit.

The spacecraft extended its docking mechanism Saturday to check the mechanical system that will link future Starliner vehicles with the space station. The ship’s stellar navigation cameras were also checked out in orbit for the first time, and the solar panel power generation system worked better than expected, according to Boeing.

The temperature and other parameters inside the Starliner’s pressurized cabin also looked OK, officials said.

But some of the Starliner’s planned maneuvers around the space station, culminating in an autonomous docking, remained unproven after the spacecraft’s first Orbital Flight Test.

And some holiday presents for the space station’s crew carried on the Starliner spacecraft went undelivered. NASA said the astronauts will get the gifts after they land on Russian Soyuz spaceships next year.

Chilton said Sunday the “big pieces” of the test flight, such as its launch and landing, have been successfully demonstrated. While a successful docking with the space station was listed before the launch as a mission objective, officials said all of the test flight’s goals were not weighted equally.

“We got a brand new human-rated Atlas 5 … flying a different trajectory, different aero-shape,” Chilton said. “You can only test that at scale. That went terrific.”

“The spacecraft got a little bit of a surprising start,” Chilton said. “The the team immediately took care of that and circularized the orbit and were able to show that his spacecraft controls attitude (and) does all the things she’s supposed to do, keeps people safe. The cabin temperature, pressures, and all that were terrific.

“Return is something that you can’t really test (on the ground),” Chilton said. “You’ve got to put your heat shield on and go through the heat regime. Today, it couldn’t really have gone any better. We got down, got guidance lock and touched down in the center of the bullseye.”

Flying some 155 miles (250 kilometers) over the South Pacific Ocean, the Starliner fired four braking rockets for 55 seconds at 7:23 a.m. EST (1223 GMT) Sunday to drop out of orbit and fall back into the atmosphere, committing Starliner to its descent toward White Sands.

Moments later the Starliner’s service and crew modules separated.

The service module — hosting the ship’s abort engines, solar panels, radiators and other no-longer-needed systems — headed for a destructive re-entry over the Pacific Ocean. Protected by an ablative heat shield, thermal tiles and blankets, the crew module used its 12 control thrusters to help guide it toward White Sands on an approach over Mexico from the southwest.

Starliner encountered the first discernible traces of the atmosphere at 7:41 a.m. EST (1241 GMT). Temperatures outside the capsule were expected to reach up to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,650 degrees Celsius).

The capsule triggered its parachute deployment sequence at an altitude of around 30,000 feet (9 kilometers).

The Starliner first jettisoned its upper heat shield and deployed a pair of drogue parachutes. Then mortars fired and pilot chutes pulled three main parachutes from their containers around 8,000 feet (2,400 meters). Less than a minute later, the capsule released its bottom heat shield, allowing airbags to inflate at around 3,000 feet (900 meters).

The ship was designed to touch down at a speed of about 19 mph (28 feet per second), and an instrumented dummy nicknamed “Rosie the Rocketeer” strapped into the Starliner cockpit was designed to register forces and loads at landing, and in other phases of the flight.

The Starliner’s landing Sunday marked the second time an orbiting crew-capable space vehicle has returned to Earth at White Sands. The shuttle Columbia returned to Earth and touched down on an unpaved landing strip at White Sands Space Harbor in March 1982 to conclude NASA’s third space shuttle mission.

Boeing plans to reuse the Starliner capsule on the program’s second piloted mission to the space station, commanded by veteran NASA astronaut Suni Williams. A separate spacecraft is being readied for Boeing’s Crew Flight Test, the first Starliner mission with astronauts on-board.

In remarks after Sunday’s landing, Williams named the capsule “Calypso” in an ode to the research vessel of French ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau.

With the post-flight Starliner data review set to get underway, Stich remained confident Sunday that astronauts will launch into orbit from U.S. soil next year for the first time since the space shuttle’s retirement in 2011.

As a program, we’ve had a tremendous year,” Stich said. “We’ve flown two orbital test flights in preparation for the crewed missions next year. We’ve flown a pad abort test in November with Boeing to test that system, and we have all the data from these two orbit test flights to set us up for crewed missions.”

SpaceX completed a successful unpiloted demonstration of its Crew Dragon spacecraft in March, when the ship accomplished an automated docking with the space station and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean off the U.S. East Coast.

But SpaceX encountered trouble in April, when the same spacecraft that completed the round-trip flight to the space station was destroyed in an explosion during a ground test-firing of its launch escape engines.

SpaceX says it has fixed the faulty valve problem that caused the explosion, and the company completed the abort engine hotfire test in November, setting the stage for an in-flight abort test in January. For the in-flight abort demonstration, SpaceX will mount the Crew Dragon — without passengers — to a Falcon 9 rocket and launch it into the stratosphere, then trigger an abort in the upper atmosphere to prove the capsule’s ability to get astronauts away from a failing booster.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.