Closing out a 27-hour pursuit after a predawn launch from Florida’s Space Coast, a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule glided to an automated docking early Sunday at the International Space Station, accomplishing one of the ship’s key test objectives before astronauts take a ride later this year.

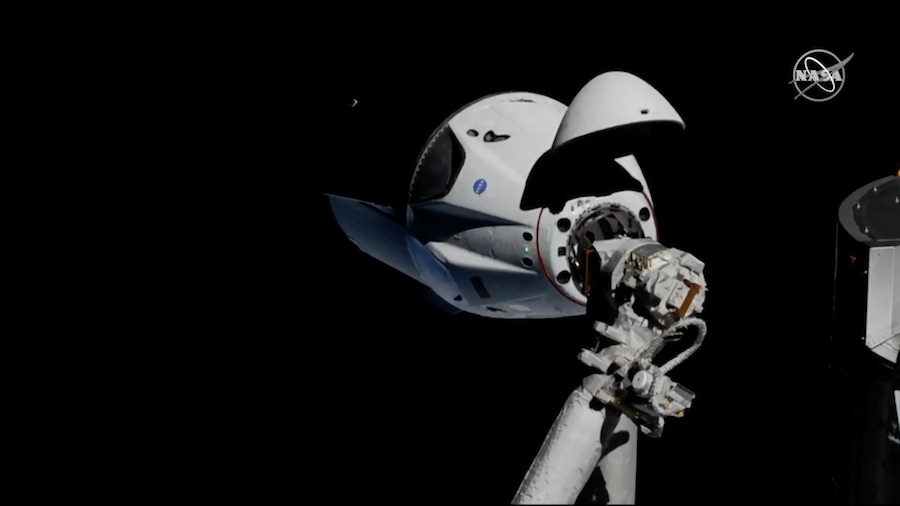

Aided by laser rangefinder and a thermal camera, the Crew Dragon approached the space station on autopilot and linked up with a docking port on the forward end of the complex at 5:51 a.m. EST (1051 GMT) Sunday, becoming the first privately-owned human-rated spaceship to reach the massive research outpost in orbit.

The link-up occurred as the station soared at an altitude of 260 miles (more than 400 kilometers) north of New Zealand, during orbital nighttime.

“Today, we welcome a brand new spacecraft to space station, a great new addition to the quiver of tools we have … to further space exploration,” said David Saint-Jacques, a Canadian Space Agency flight engineer and member of the station’s Expedition 58 crew. “This is the first day of a new era for the next generation of space explorers.”

The only passengers aboard the Crew Dragon during Sunday’s docking were an instrumented test dummy named “Ripley,” a plush toy Earth added as a low-tech zero-gravity indicator, and cargo containers stowed under the ship’s four seats.

The next time a Crew Dragon spacecraft reaches the station, a two-man team of NASA astronauts will be on-board, seeking to become the first people to fly into Earth orbit on a U.S.-built spacecraft since the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011.

The docking was a critical moment in the Crew Dragon’s six-day demonstration flight — named Demo-1 or DM-1 — which SpaceX and NASA designed to wring out the ship’s power, electrical, thermal control, navigation, life support, and docking systems, among other components necessary to ferry astronauts to and from the space station.

It was also a crucial milestone for NASA’s efforts to shepherd commercial spaceflight development, a strategy first implemented with the agency’s funding of commercial cargo vehicles to deliver supplies to the space station, then expanded in the commercial crew program.

NASA has paid U.S. companies more than $8 billion since 2010 to design and develop new human-rated spacecraft, ending U.S. space agency’s reliance on Russian Soyuz crew ferry ships for astronaut transportation since the last space shuttle mission. The new commercial capsules will be owned and operated by companies, not NASA.

Here’s a replay of Crew Dragon’s arrival at the International Space Station, a critical event before astronauts ride the spaceship later this year. https://t.co/DcjwNciGlg pic.twitter.com/nr5RiGFbRL

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) March 3, 2019

SpaceX and Boeing are in the final stages of readying their commercial crew capsules for astronauts after nearly a decade of work, including years of delays caused by shortfalls in funding from Congress, technical hurdles and redesigns. After SpaceX’s Crew Dragon test flight concludes later this week, Boeing is scheduled to launch its first CST-100 Starliner capsule on a similar unpiloted demonstration mission to the space station this spring.

On Sunday, the Crew Dragon initially approached the station from below, then pulsed thrusters to maneuver to a position ahead of the outpost, along the station’s velocity vector, or direction of travel.

The gumdrop-shaped spaceship briefly paused its approach after astronauts inside the space station tested a radio link with the capsule by sending the Crew Dragon a retreat command, proving the station residents could tell the capsule to fly away if it encountered a problem.

Ground teams at SpaceX mission control in Hawthorne, California, and NASA’s control center in Houston gave a final “go” for docking as the Crew Dragon spacecraft held position around 66 feet (20 meters) from the station.

With a nose cone folded opened to reveal its docking port, the capsule fired its Draco thrusters again to begin the final approach, closing in on the station at a relatively velocity of around 0.2 mph, or about 10 centimeters per second.

Sensors in the Crew Dragon’s docking port detected contact with the station at 5:51 a.m. EST, nine minutes ahead of schedule, and latches engaged to create a preliminary connection with the space station’s International Docking Adapter at the forward end of the Harmony module.

The station docking adapter was installed over the space shuttle’s old docking port, and the Crew Dragon’s arrival Sunday marked the first time a visiting spaceship docked there since the last flight of the shuttle Atlantis in 2011.

A few minutes later, 12 hooks closed to form a firm mechanical connection between the Crew Dragon and space station. Two umbilical lines were robotically mated through the docking port to allow the station’s electrical power to feed the Crew Dragon during its stay.

After a series of leak checks and pressurization of the passageway leading to the SpaceX capsule, Saint-Jacques opened the Crew Dragon’s hatch at 8:07 a.m. EST (1307 GMT) and became the first person to board the ship. Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko, commander of the station’s Expedition 58 crew, joined Saint-Jacques to collect air samples inside the spacecraft.

Saint-Jacques and Kononenko wore protective masks as a safety precaution, a common practice by space station crews when entering new visiting vehicles. No contaminants were found inside, and mission control cleared the crew to take off their masks and turn on fans to circulate air between the space station and Crew Dragon.

The astronauts quickly got to work unpacking some 450 pounds (204 kilograms) of equipment and crew supplies stowed under Crew Dragon’s four seats.

The Crew Dragon hatch is open, and astronaut David Saint-Jacques and cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko are the first humans inside the SpaceX capsule in orbit. https://t.co/DcjwNciGlg pic.twitter.com/xJBCz8jxRP

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) March 3, 2019

Anne McClain, a U.S. Army helicopter pilot-turned-NASA astronaut, recorded a video greeting from the Crew Dragon, alongside Ripley, the mannequin named for the protagonist in the “Alien” film franchise, and the floating toy Earth.

“On behalf of Ripley, little Earth, myself and our crew, welcome to the Crew Dragon,” she said. “Congratulations to all of the teams who made yesterday’s launch and today’s docking a success. These amazing feats show us not how easy our mission is, but how capable we are of doing our things. Welcome to the new era in spaceflight.”

McClain later tweeted an image of the Crew Dragon’s silhouette set against the Earth’s horizon, writing that Sunday’s docking was the “dawn of a new era in human spaceflight.”

The dawn of a new era in human spaceflight pic.twitter.com/BHsfg1zYLN

— Anne McClain (@AstroAnnimal) March 3, 2019

Astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, assigned to the first Crew Dragon test flight with humans on-board, were at SpaceX’s headquarters in California for Sunday’s docking. They traveled across the country from Florida, where they viewed the Crew Dragon’s launch early Saturday.

“It’s just been a super exciting week for us,” Behnken said after Sunday’s docking. “We came from Florida after watching the launch, got on orbit, got activation done, and the next big milestone was autonomous docking, and getting that demonstrated.

“Of course, the station crew is monitoring, but that’s how we’re going to be getting Dragon on-board, docked on station in the future. So it was just super exciting to see it,” said Behnken, a veteran of two space shuttle missions in 2008 and 2010.

Behnken said flying on the Crew Dragon will be a different experience than flying on the space shuttle, which required four people on the flight deck to manually control the vehicle and monitor systems.

“Doug and I will do it (on Crew Dragon) for the first time together, primarily in a monitoring role,” Behnken said. “We may push a button or two to demonstrate that we have the capability to intervene if we need to, but the vehicle is pretty much going to do the work autonomously, just like it did today.”

The Crew Dragon launched on its journey to the space station at 2:49 a.m. EST (0749 GMT) Saturday from pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The capsule rocketed away from Florida’s Space Coast toward the northeast atop a Falcon 9 launcher, and deployed from the Falcon 9’s upper stage around 11 minutes after liftoff. Moments later, the spaceship opened its nose cone to reveal its docking mechanism and navigation sensors, and began a sequence of thruster burns to boost its orbit toward the space station.

The Crew Dragon is set to depart the station early Friday, with undocking planned at 2:31 a.m. EST (0731 GMT), followed by a deorbit burn at 7:50 a.m. EST (1250 GMT).

The spaceship will jettison its unpressurized trunk section, where its solar panels and radiator are located, to burn up in Earth’s atmosphere. Protected by a heat shield, the crew cabin will re-enter the atmosphere flying northwest to southeast, heading for a splashdown under four parachutes in the Atlantic Ocean east of Cape Canaveral at 8:45 a.m. EST (1345 GMT).

SpaceX designed the Crew Dragon spacecraft as the company flew the first-generation Dragon capsule on resupply missions to the space station. Under contract to NASA, the cargo Dragon variant has launched 18 times since 2010, including two test flights and a mission cut short by a Falcon 9 rocket failure.

“Dragon 2, or Crew Dragon, is a fundamental redesign,” said Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, in a press conference after Saturday’s launch. “There’s hardly a part in common with Dragon 1.”

The space station’s robotic arm snared SpaceX’s previous Dragon capsules as they delivered supplies. The Crew Dragon, which will also carry cargo, can dock by itself, a capability demonstrated Sunday.

Another big change introduced with the Crew Dragon is the capsule’s launch escape system. Eight high-thrust SuperDraco engines are mounted around the circumference of the spaceship, ready to push the capsule away from a catastrophic launch failure. Other crew capsules have launched with top-mounted escape rockets, which jettison and fall back to Earth after reaching space.

“In the case of Dragon, they’re integrated, so you have an abort capability all the way to orbit, and you do not have to worry about a separation event of the launch escape system,” Musk said. “This is, I think, quite a big safety improvement, in principle.”

Musk said Saturday that the Crew Dragon’s re-entry is “probably my biggest concern” about the mission.

“The backshell is not symmetric in the way that Dragon 1 is,” Musk said. “It’s not sort of a smooth conic like Dragon 1. You’ve got the launch escape thruster pods. That could potentially cause a roll instability on re-entry.

“I think it’s unlikely. We’ve run simulations a thousand times, but this is a possibility. I think the re-entry, with an asymmetric backshell, and then the parachutes are new. Will the parachutes deploy correctly? Will the system guide Dragon 2 to the right location, and splash down safely?”

If all goes well, NASA hopes SpaceX or Boeing will be ready to fly people to the space station later this year.

SpaceX’s next Crew Dragon test flight, known as Demo-2 or DM-2, is currently set for July. Officials admit that schedule is tight and assumes a problem-free Demo-1 mission, a quick turnaround for a high-altitude test of the Crew Dragon’s launch escape system, and final closure of unresolved technical concerns involving the Falcon 9 rocket’s high-pressure helium tanks, the spaceship’s thrusters and parachutes.

Read our earlier story for details on the issues NASA says must be addressed before astronauts fly on Crew Dragon. The Starliner capsule has its own technical concerns, adding uncertainty to Boeing’s test flight schedule.

Boeing test pilot Chris Ferguson, a former NASA astronaut, will command the Starliner’s first test flight with a crew on-board. He will be joined by veteran NASA space flier Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann, a spaceflight rookie.

Once the Crew Dragon and Starliner capsules complete their crewed demonstrations, the commercial spaceships will begin regular flights to rotate astronauts between Earth and the space station for six-month expeditions.

Each capsule is designed to carry up to seven astronauts, but they typically will launch and land with four crew members, plus some cargo.

In a hedge against further delays, NASA is considering an option to buy two more Soyuz seats from Russia’s space agency — Roscosmos — for U.S. astronauts to travel to the space station in late 2019 and early 2020, with landings extending through September 2020.

The last launch under NASA’s current contract for Soyuz seats is scheduled in July, when astronaut Drew Morgan, Italian flight engineer Luca Parmitano and Russian cosmonaut Alexander Skvortsov will blast off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

NASA could also extend the mission of Boeing’s Starliner crewed test flight, allowing Ferguson, Fincke and Mann to stay on the space station for months, ensuring NASA astronauts are on-board to operate the U.S. modules at the research outpost.

Once NASA declares the SpaceX and Boeing commercial crew capsules are operational, NASA and Roscosmos will fly their crew members on both U.S. and Russian vehicles on an in-kind basis, without exchanging money. The barter arrangement will help ensure a Russian cosmonaut and a U.S. astronaut are always on the space station if the Soyuz, Crew Dragon, or Starliner capsules are grounded.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.