EDITOR’S NOTE: SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft successfully launched March 2, and docked with the International Space Station on March 3.

The astronauts assigned to fly SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft beginning later this year said Friday they are excited for the capsule’s first orbital mission set for launch Saturday, but significant work remains before the ship is cleared to carry people.

“There’s something really exciting about being first, getting to fly a crewed mission coming out of this,” said Bob Behnken, a veteran astronaut assigned to join NASA crewmate Doug Hurley on the Crew Dragon’s first trip to space with humans on-board later this year.

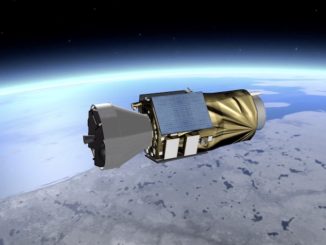

The Crew Dragon spacecraft — the product of a multibillion-dollar public-private partnership between NASA and SpaceX — is poised to launch into orbit for the first time Saturday at 2:49 a.m. EST (0749 GMT) from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The only passenger aboard the Crew Dragon during Saturday’s launch is an instrumented mannequin named “Ripley,” which is positioned in one of four seats inside the ship’s pressurized crew compartment. SpaceX and NASA engineers will use the Crew Dragon’s six-day mission to and from the International Space Station — known as Demo-1 or DM-1 — to collect data on the capsule’s performance, safety and reliability.

“This is kind of the next critical step in putting people on Dragon,” Hurley told reporters Friday at KSC. “So we’ve got this flight, and then we’ve got the in-flight abort and then, ideally, our flight soon to follow. I can’t begin to explain to you how exciting it is for a test pilot to be on the first flight of a vehicle, and we’ll be ready when SpaceX and NASA are ready for us to fly it.”

“I’m very comfortable with where we’re heading toward this (Demo-1) flight,” said Bill Gerstenmaier, associate administrator of NASA’s human exploration and operations directorate. “I fully expect we’re going to learn something on this flight. I guarantee everything will not work exactly right, and that’s cool. That’s exactly what we want to do. We want to maximize our learning.”

NASA and SpaceX have officially targeted Behknen and Hurley’s flight — called Demo-2 or DM-2 — for no earlier than July, but officials consider that schedule optimistic, assuming a smooth unpiloted Crew Dragon test flight, a seamless turnaround of the Demo-1 capsule for an in-flight abort to test the ship’s escape thrusters, and the closeout of several unresolved technical concerns NASA says must be addressed before its astronauts can fly.

As a hedge against additional delays, the U.S. space agency is considering purchasing two more seats from Russia to allow its astronauts to launch to the space station on Soyuz spacecraft in late 2019 and early 2020.

Once SpaceX’s Crew Dragon and Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner, another capsule funded by NASA, accomplish their unpiloted and crewed test flights, both spacecraft can commence regular crew rotation missions to the station, ending U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz capsules for transportation to and from low Earth orbit.

NASA is also weighing an option to extend Boeing’s crewed test flight, with three astronauts on-board, from a short stay to a long-duration mission lasting multiple months. The longer mission could help ensure U.S. astronauts remain on the station — a major concern of NASA managers — in the event of further delays in certifying the Crew Dragon and Starliner for operational flights.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said Friday he remains confident U.S. astronauts will launch on at least one of the commercial crew capsules before the end of the year. The crewed test flights will be the first time a U.S. spacecraft has launched into orbit with astronauts since the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011.

“I would say I’m very confident,” Bridenstine said. “In fact, you can write in your article I’m 100 percent confident because, as far as I’m concerned, you’re either for it or you’re not, and I think we’re going to get it done.”

Engineers will analyze data gathered on the Demo-1 test flight, searching for areas that might need improvement before crews board the spaceship.

“I think, as a team, we would all agree that we probably aren’t ready for the Demo-2 mission,” Behnken said Friday. “We expect to get a lot of data from this one that will provide us with a better understanding of what we face when we jump into that actual test flight in preparation for expedition crews that come after us.”

NASA astronauts Mike Hopkins and Victor Glover will launch on the Crew Dragon’s first regular crew ferry mission to the station after Behnken and Hurley’s test flight. Hopkins and Glover are slated to spend around six months aboard the orbiting research complex, then return to Earth on the Crew Dragon.

Hopkins said astronauts — if asked — would be ready to fly on Crew Dragon, but added that it is important to send the ship to space on a demonstration mission before adding humans to the mix.

“I think there are important reasons why, if we can, we don’t put crew on something of a first flight like this for safety reasons, and I think that’s smart,” Hopkins said. “If we were going to be on that, I think it would probably be a little bit different process getting to this point. Maybe you’d evaluate some of the risks a little bit differently.”

NASA launched the space shuttle on its first flight with two astronauts on-board, breaking with the convention followed in the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs of sending up spacecraft without people.

“If we were to try and do it with that approach, it would take us a lot longer,” Glover said. “I’m very happy that we’re doing it this way, and we’re going to get Bob and Doug up there to finish shaking out (the spacecraft) … and make sure that we’re ready to go when we do a long-duration mission.”

The Crew Dragon will splash down in the Atlantic Ocean — around 240 miles (390 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral — to wrap up the Demo-1 mission March 8. A SpaceX recovery ship will retrieve the capsule from the sea and return it to port.

SpaceX aims to reuse the capsule for an in-flight abort test, tentatively scheduled for June, to verify the performance of the ship’s escape engines.

The in-flight abort test will verify the Crew Dragon’s SuperDraco escape thrusters can push the capsule away from a failing rocket, a safety feature designed to ensure astronauts survive a launch accident.

Eight SuperDraco rocket engines mounted in pods around the circumference of the Crew Dragon are programmed to quickly fire if computers detect an emergency during launch. NASA and SpaceX want to ensure the escape system is up to the job before putting astronauts on the spacecraft.

SpaceX tested the abort system during an on-pad test in 2015, demonstrating the SuperDracos have the power to drive the spacecraft off its rocket sitting on the ground in the event of an accident during the countdown.

For the Demo-1 mission, the escape system is operating with reduced functionality to gather data. An on-board computer will track the health, orientation and rates of the Falcon 9 rocket during its climb into orbit, with safety triggers relaxed to ensure the escape system does not inadvertently activate during the launch.

“You have certain parameters, like a rate, or angular position, at certain limits, but for crew, you would cut it maybe a little bit closer, just to make sure it’s safer, and it triggers earlier,” said Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability.

Crew Dragon’s life support system, including air revitalization equipment to regulate oxygen and carbon dioxide inside the spaceship, will be up and running on the Demo-1 mission. The crew seats and display monitors will also fly.

But some equipment, such as crew controls, push buttons and the toilet, are not on the Crew Dragon on the Demo-1 test flight. SpaceX will add those components for the first mission with astronauts.

Engineers are also still assessing concerns with high-pressure helium tanks — known as composite overwrapped pressure vessels, or COPVs — parachutes and thrusters, according to Gerstenmaier.

The COPVs contain helium pressurant for the Falcon 9’s propellant tanks, and SpaceX introduced an upgraded helium reservoir that began flying on the rocket late last year. The new COPV design — dubbed COPV 2.0 — includes fixes intended to avoid friction in the fibers on the outside of the tank, which engineers believe could create a spark.

Investigators probing the explosion of a Falcon 9 rocket on its launch pad in 2016 blamed the accident on a spark generated from a helium vessel inside the vehicle’s upper stage liquid oxygen tank.

More than two years after the 2016 accident, Gerstenmaier said engineers are still working to understand how friction on the outside of a COPV could spark such a catastrophic explosion.

“The way we do things in human spaceflight is we need to not only meet the design, but we need to understand physically which parameters are driving a bad outcome,” Gerstenmaier said. “So, for example, what are the ignition parameters that can cause a COPV to ignite, and then we need to show physical controls in how we prevent those individual physical parameters from contributing to the final event.

“I think we’ve done … the statistical analysis that says this is a very low probability event,” Gerstenmaier said. “It’s not going happen very often, but now we are going through what are the physics behind that? What could be an ignition source?

“One of the things, the composite overwrapped pressure vessel has fibers that are twisted together … As those pressurize, they can break, and as they break, they can potentially generate heat,” Gerstenmaier said. “If they can generate enough heat in the oxygen environment, they can be an ignition source. So now we’re going back, and we’re proving to ourselves that this breaking is so unlikely that it’s not going to be a concern to cause the ignition event and cause a problem moving forward.”

While there are several technical issues NASA wants to resolve before the Crew Dragon carries astronauts, officials approved plans to go ahead with the unpiloted demo flight.

“We’re working several other things on this vehicle that we just discovered, so I would say the vehicle is not fully qualified,” Gerstenmaier said. “In other words, we haven’t set the total envelope of where some of the hardware can operate and how it can be used, but we know the hardware is good enough to go do this demonstration flight. In fact, we want it to go to flight to see if there’s something else we missed.

“We fully expect to learn some things on this flight, and then we’ll go through a more rigorous kind of problem-solving method,” Gerstenmaier said. “We’ll do that with each one of these things. There’s some stuff in the thruster area, there’s some stuff in the parachute area, there’s some stuff in the propellant system area, some more composite overwrapped pressure vessels actually on the Dragon tank, etc. So there’s a handful of things. This is very typical. We find these things out, we figure out how to work them.”

Drop testing of a Crew Dragon mock-up continues to collect data on the ship’s four parachutes, and engineers are modifying part of the capsule’s propulsion system to address a vibration concern with the ship’s Draco thrusters, used for orbital adjustments and attitude control.

“We’re looking at the physical parameters of how the chutes operate. Have we covered all the corners of the envelope in testing? So the teams are still doing prachute drops. They’re still doing parachute testing. That needs to be completed,” Gerstenmaier said.

NASA and SpaceX officials said the Draco thruster concern is centered on how the rocket jets behave when cold propellants are injected into them. The Crew Dragon carries 16 Draco rocket thrusters, burning a hypergolic mixture of hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants.

“It’s a shock event, basically,” Koenigsmann said. “There’s shock waves that can break things. We found that it’s dependent on temperature. When you keep the propellant warm, it’s actually going away.”

“For this (mission), the solution is to keep the propellant warm operationally,” Koenigsmann said. “In the long run, we will have heaters on (propellant) lines and make sure.”

On the Demo-1 flight, ground controllers will keep the Crew Dragon in orientations to ensure the propellant tanks remain illuminated and heated by the sun. When docked to the station, controllers can keep the propellants warm by managing the power load inside the spacecraft, according to Koenigsmann.

“The thruster shock can be so strong that it damages the thruster, so physical damage. But it’s super unlikely. We’ve had 16 (Dragon cargo) missions. It’s the same thruster,” Koenigsmann said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.