NASA announced Thursday nine companies that will be eligible to compete for up to $2.6 billion in contracts over the next decade to ferry scientific instruments and tech demo payloads to the moon aboard commercial robotic landers, a first step in what agency officials said will foster expanded private investment in deep space exploration and an eventual return of humans to the lunar surface.

The nine companies selected by NASA will own and operate the robotic lunar landers, while NASA buys capacity on the spacecraft to place research equipment. That represents a change in NASA’s traditional way of developing missions to the moon and other solar system destinations, in which the government funds, owns and oversees every aspect of the project.

“We’re doing something that’s never been done before,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. “When we go to the moon, we want to be one customer of many customers in a robust marketplace between the Earth and the moon, and we want multiple providers that are competing on cost and innovation.”

Bridenstine said the Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS (pronounced “clips”), program is one way NASA seeks to jump-start a stagnant U.S. lunar exploration program, which has seen starts and stops under past presidential administrations. The Trump administration has instructed NASA to re-emphasize the return of astronauts to the lunar surface, a goal that was bypassed in favor of a focus on Mars exploration under the Obama White House.

The NASA chief said the inclusion of commercial companies, like the winners announced Thursday, will make the current lunar exploration effort “more resilient” than those of the past.

“The reason this is more resilient than before is because we have commercial customers that aren’t necessarily NASA … and we have international partners on a level that we’ve never seen before on this planet — more partners than ever before,” Bridenstine said.

While a landing by astronauts on the moon’s surface is still a decade or more away, NASA wants to return U.S. science payloads to the lunar surface much sooner, and at a bargain. NASA has selected nine companies to be eligible for bids to carry NASA-sponsored experiments to the moon, beginning as soon as next year:

- Astrobotic Technology Inc., based in Pittsburgh

- Deep Space Systems, based in Littleton, Colorado

- Draper, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Firefly Aerospace Inc., based in Cedar Park, Texas

- Intuitive Machines LLC, based in Houston

- Lockheed Martin Space, based in Littleton, Colorado

- Masten Space Systems Inc., based in Mojave, California

- Moon Express, based in Cape Canaveral, Florida

- Orbit Beyond, based in Edison, New Jersey

Those companies will be able to bid on NASA task orders to haul specific instruments and payloads to the moon’s surface, initially aboard small, stationary landers, but perhaps eventually on bigger spacecraft and mobile rovers. The announcement Thursday did not commit government funding to any of the companies, but only made the winners eligible to compete for mission task orders yet to be released by NASA.

In the end, some or all of the companies may win NASA contracts for lunar lander missions. None of the competitors announced Thursday is guaranteed a contract win, and NASA is not funding any of the landers’ development costs, which must be financed through other sources.

“The companies … are becoming part of the catalog,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, head of NASA’s science mission directorate. “As part of that, they will compete for tasks that we’re going to put out there weeks and months from now. So we’re not going to sit on our hands on this, and (we’ll) start to put tasks out.

“How they’re going to bid that exactly is entirely up to them,” Zurbuchen said. “They’re also going to choose how they can get to the moon.”

The companies will provide an “end-to-end” service to NASA, with the contractors responsible for choosing launch vehicles, building and operating the lunar lander spacecraft, and potentially Earth return vehicles for sample collection missions.

The CLPS contracting scheme is similar to the way NASA’s Launch Services Program procures rockets for the agency’s scientific satellites. Several companies are eligible to compete for such launches, and NASA releases task orders for each specific mission, receives bids, and then selects a winner to execute the mission.

Zurbuchen said the CLPS program’s catalog of companies will change over time, as potential lunar lander provides merge, evolve, or perhaps leave the program. There will also be opportunities for more companies to be added to the catalog, he said.

NASA hopes to build up commercial lander capabilities in the early-mid 2020s to eventually result in the development of a human-rated lander late in the next decade. In parallel with the commercial moon missions, NASA aims to construct a mini-space station, or Gateway, in lunar orbit in the 2020s, which could serve as a staging point for landers going to and from the moon’s surface.

Space agency officials say the return to the moon will pave the way for an eventual human mission to Mars. But many details about the Gateway’s construction and funding have not been finalized, and plans for a crewed mission to Mars remain tenuous.

While NASA has selected the companies it says will return U.S. hardware to the moon’s surface for the first time since 1972 — when the last Apollo crew landed — the agency is now considering which instruments will be ready to launch on the commercial moon probes, perhaps as soon as the end of 2019.

“We believe there is a lot of amazing science that we can do on the surface of the moon, in fact, science that we can’t do anywhere other than the surface of the moon,” Bridenstine said. “Our cost and our risk is lower than it otherwise could be, and we have multiple providers that are competing on cost and innovation.”

NASA released a request for proposals for the CLPS program in September, and proposals were due Oct. 9. Agency officials did not disclose how many companies submitted proposals for the CLPS program, but a list of “interested parties” published on the federal government’s FedBizOpps procurement website included 28 companies. The interested parties list included SpaceX and Blue Origin, two of the biggest privately-backed space companies, but neither were selected by NASA, and it’s not known whether they submitted proposals.

Nevertheless, the CLPS program is focused on fielding small lunar landers capable of launching within the next two years. SpaceX and Blue Origin are working on larger vehicles — SpaceX on the giant BFR launcher and spaceship, and Blue Origin on the robotic “Blue Moon” lunar lander — and neither are projected to be ready for moon missions until 2023 or 2024, at the very earliest.

“Think of it like venture capital,” Bridenstine said of NASA’s support for the commercial lunar lander programs. “Our investment is low because we have other people that are investing. Our investment is low, the risk is higher than it would otherwise be, but we have more providers. In other words, the portfolio is larger so we can take risk.

“We’re taking shots on goals here. We’re trying to get it done fast,” he continued. “We’re trying to very quickly develop an American capability to deliver small payloads to the surface of the moon, and then grow from there. We want medium-class landers, we want large-class landers, and of course, we’re going to have human-class landers within a decade. All of that being said, we also want to get there fast.”

The commercial lunar lander initiative is an extension of NASA’s effort to commercialize crew and cargo transportation in low Earth orbit.

NASA selected SpaceX and Northrop Grumman — then Orbital Sciences Corp. — in 2008 to haul supplies and experiments to the International Space Station, replacing logistics services previously provided by the space shuttle, which retired in 2011. In 2014, NASA awarded SpaceX and Boeing a combined $6.8 billion in contracts to develop, build and fly new commercial crew capsules for astronaut transportation.

Commercial cargo missions started flying to the station in 2012, and commercial crew flights are scheduled to begin next year.

“We’re taking what we’ve learned from our experience with the International Space Station to drive down cost and increase access, and we’re applying it to cislunar space,” Bridenstine said.

Steve Clarke, associate deputy administrator for exploration in NASA’s science division said the CLPS program is a “lean forward” for the agency.

“Typically, we procure satellites and probes that are unique for each mission,” he said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “This is completely different, where we’re actually buying a ride. We’re going to provide the payloads. We’re going to provide the science instruments, even some technology demonstration experiments and units, and provide those to these companies to fly to the surface of the moon.

“They’re providing the lander, and they’re also providing the launch. They provide the whole package to give us the ride to the surface.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Steve Clarke. Become a member today and support our coverage.

Clarke said NASA will ask each company for a “payload user’s guide” detailing the design and capabilities of their lunar lander concepts, similar to user’s guides published by launch service providers. The guides will be released publicly, allowing scientists and engineering teams to match their designs with the lander’s mass, power, and communications capabilities.

“Once we select the instruments, and the criteria for that is near-ready to fly or almost-ready to fly payloads, we will marry up the instruments from a capability standpoint and mass with what the landers can provide,” Clarke said.

The first round of instruments to fly on the commercial lunar landers could be passive retroreflectors, which require no power or data relay. The reflectors, similar to ones left behind by the Apollo astronauts and Soviet lunar rovers, are used for laser ranging between Earth and the moon, and could aid navigation for future lunar missions.

“Now that we’ve penned the contracts, we can immediately start issuing task orders,” Clarke said.

“One of the things we’re looking at is the laser retroreflectors,” he said. “We’d like to fly retroreflectors because they do not require power. They do not require communications. We’d like to fly them on every landed mission going forward, either U.S. commercial, or international, if they’re willing to accommodate those. So I can foresee us issuing a task order to have the lander companies that we heard from today fly those retroreflectors.

“The more landings we have, and we have these retroreflectors aboard, we’ll be able to start navigating future missions to land on the moon because they’ll be able to know where each of the other landers are. It’s almost like a geolocation-type network that we’d like to build.”

Other instruments flying to the moon on the commercial landers may include sensors to sniff out the presence of water ice, a potential resource that could be used to supply lunar fuel depots, and provide drinking water and breathable air to astronauts. A landing on the far side of the moon could be useful to astronomers because the environment there is free from interference from radio emissions, such as human-made transmissions from Earth, or natural emissions from the sun.

Earlier this year, NASA canceled a lunar rover mission named Resource Prospector, which aimed to test technology to search for water bound in lunar rocks at one of the moon’s poles. But NASA determined the rover’s four instruments, such as spectrometers, a regolith and ice drill, and an experiment to heat lunar samples to quantify water content, were technically mature enough to fly on commercial landers.

NASA has put out a call for instruments that could be ready to launch on commercial lunar landers within the next year.

Many of the CLPS competitors are supported by groups of subcontractors. In Astrobotic’s case, Airbus Defense and Space, United Launch Alliance, Dynetics and Northrop Grumman are supporting development of the Peregrine lander, scheduled to launch for the first time by the end of 2020. Moon Express is partnering with Sierra Nevada Corp., Paragon Space Development Corp., NanoRacks and Odyssey Space Research, and has launch contracts with Rocket Lab. The Moon Express lunar missions could begin in 2020.

Draper’s lunar lander team includes General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems, the Japanese company ispace, and Spaceflight Industries, which will arrange the craft’s launch services. Officials from ispace previously said they planned to launch their initial commercial lunar missions as piggyback payloads on SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets — first an orbiter in 2020, followed by a lander in 2021.

Masten Space Systems, founded in 2004, has progressively tested more advanced vertical takeoff and vertical landing testbeds at its test site in California’s Mojave Desert. The company says it could be ready to launch a robotic lunar lander by the end of 2021.

Orbit Beyond is a new name in the commercial lunar lander marketplace, but the New Jersey-based company leads a consortium of subcontractors who have designed and developed hardware for deep space missions. Team Indus, an Indian company, is leading Orbit Beyond’s lander engineering, and payload integration tasks will be managed by Honeybee Robotics, which built hardware for several NASA Mars landers.

“There has never been a more exciting time to be a commercial player in the cislunar market,” Jeff Patton, chief engineering advisor at Orbit Beyond, and a systems integration and engineering manager at United Launch Alliance. “We believe to enable space exploration, the cost of delivering and operating payloads to beyond earth orbit destinations has to come down by an order of magnitude. Winning the NASA CLPS contract will enable OrbitBeyond to deliver its first lunar landing mission as early as 2020.”

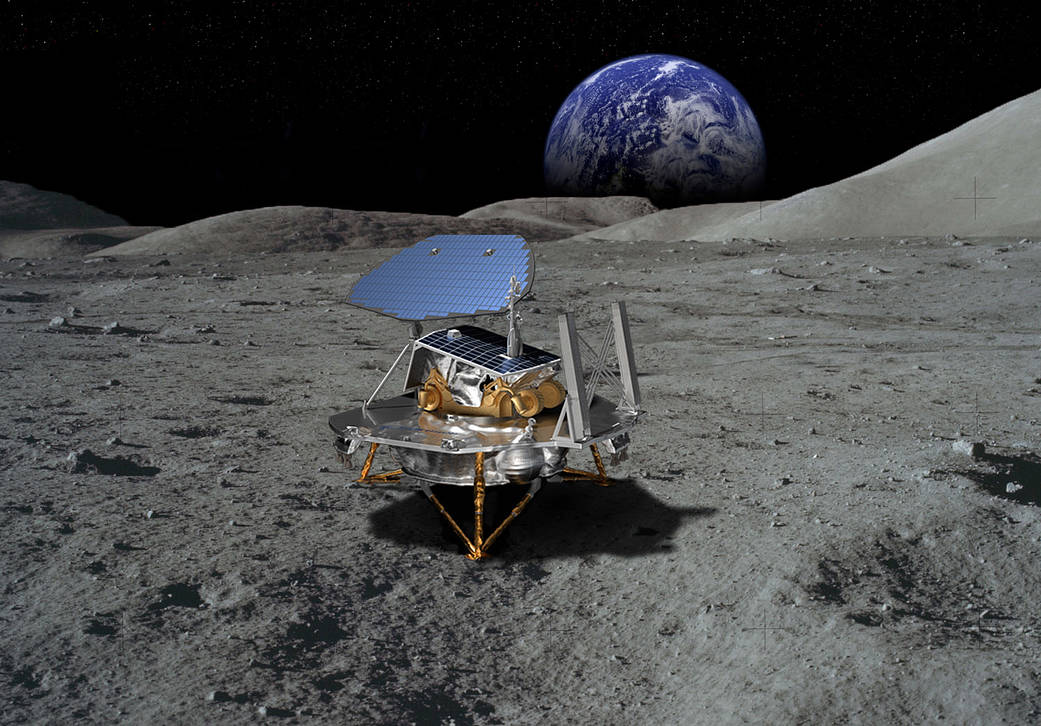

Lockheed Martin proposed a concept called the McCandless Lunar Lander, based on the design of the InSight Mars lander that reached the red planet Monday. It’s one of the biggest lander concepts from the companies selected by NASA, capable of carrying hundreds of kilograms of scientific instrumentation, deployable rovers and sample return vehicles to the lunar surface.

Information released by the other CLPS competitors suggest their initial lunar lander missions will be able to haul tens of kilograms — and perhaps up to 100 kilograms (220 pounds) — of scientific and technology demonstration equipment to the moon’s surface.

In some ways, the CLPS program is a continuation of the defunct Google Lunar X Prize, which offered a $20 million grande prize for the first privately-funded spacecraft to land on the moon, send back video and images, and rove across the surface. Moon Express, ispace, Team Indus and Astrobotic were all competing for the prize, among other companies, and now have roles in NASA’s lunar lander initiative.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.