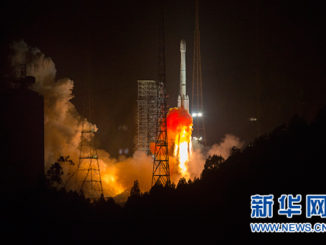

Ground crews in French Guiana on Monday transferred an Ariane 5 rocket to its launch pad, moving the vehicle into position for liftoff Wednesday with four European Galileo navigation satellites on the Ariane 5’s last flight with an older-generation, out-of-production upper stage.

The 1.7-mile (2.7-kilometer) journey from the Ariane 5’s final assembly building to the ELA-3 launch pad at the Guiana Space Center took about one hour, with the 155-foot-tall (47-meter) rocket riding a mobile platform pulled by a diesel-powered tug along dual rail tracks.

Once at the launch pad, the Titan tug positioned the rocket and its mobile platform over a flame bucket, and technicians connected the Ariane 5 to power, telemetry, propellant, pressurant and conditioned air supplies. Pre-launch steps planned for Tuesday included filling of the rocket’s helium pressurization system in preparation for the final countdown, timed for launch from the European-run spaceport in South America at 1125:01 GMT (7:25 a.m. EDT; 8:25 a.m. French Guiana time).

The Ariane 5 rocket has an instantaneous launch opportunity Wednesday, or else wait for another day.

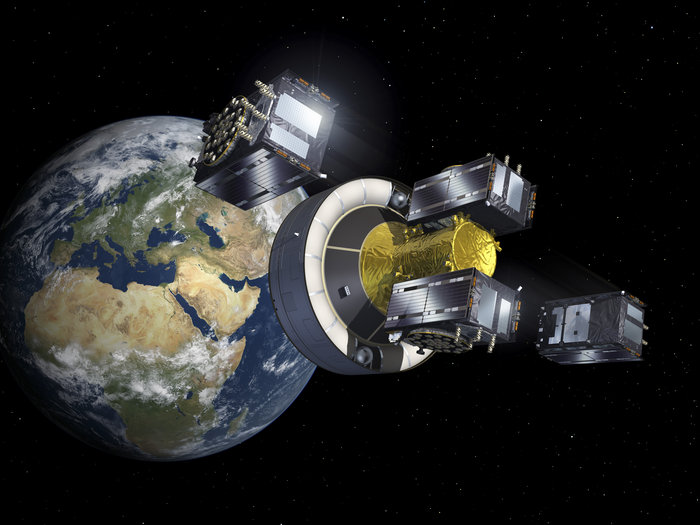

A quartet of Galileo satellites is mounted atop the Ariane 5 launcher, ready to advance the deployment of Europe’s home-grown navigation network.

“Here on site, everything is ready,” said Paul Verhoef, director of navigation at the European Space Agency. “The launcher is ready. The site is ready.”

ESA is a technical and procurement agent on the multibillion-euro Galileo program, which is managed by the European Commission, the executive arm of the European Union.

Wednesday’s launch is a turning point for the Galileo program, which is projected to cost EU member states 10 billion euros ($11.7 billion) from inception through 2020. With a successful mission Wednesday, ESA and the European Commission will have launched 26 Galileo satellites since 2011, keeping the network on track for full operability in 2020, Verhoef said in a conference call with reporters Tuesday.

Once complete, the Galileo constellation will be made up of around 30 satellites, including 24 operational spacecraft and approximately six spares spread among three orbital planes 14,429 miles (23,222 kilometers) above Earth.

The satellites due for liftoff Wednesday are the last of a a second batch of navigation platforms ordered from OHB of Germany, which builds the spacecraft, and British-based SSTL, provider of the navigation payloads.

There will be a hiatus in Galileo launches until late 2020, when the first pair of an additional 12 Galileo satellites ordered from the OHB/SSTL team by ESA and the European Commission will be ready for liftoff. The next series of Galileo satellites are expected to launch on Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket, riding two at a time aboard the lighter configuration of the next-generation launcher with two solid solid rocket boosters.

“We are happy with what we have at the moment, and with the delivery of the next batch in 2020,” Verhoef said.

Officials said the addition of the four satellites set for launch Wednesday — along with the eventual incorporation of two Galileo spacecraft launched into an incorrect orbit in 2014 and the activation of Galileo’s ground systems — should allow the European Commission to declare the network ready for full operations in 2020.

The European Commission kicked off Galileo’s initial services in December 2016, allowing users equipped with Galileo-enabled chipsets to incorporate Galileo navigation signals alongside those provided by the U.S. military’s GPS satellites and the Russian military’s Glonass fleet.

But without a full complement of at least 24 satellites, there are still gaps in Galileo coverage. Besides the two Galileo satellites flying in the wrong orbit, another spacecraft suffered an antenna failure and is unable to provide services.

Nevertheless, officials said those gaps will be closed in the next few years, and the satellites that are working in orbit are providing better-than-required positioning estimates.

“Not only is the Galileo performance promised to be very good, it is very good,” said Rodrigo de Costa, Galileo services program manager at the European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Agency, or GSA.

The full operational capability milestone means “the constellation is complete, fully operational, with all the ground segment,” Verhoef said.

“This is often forgotten,” Verhoef told reporters Tuesday. “The focus is always that we launch satellites, but I can tell you a lot of the deployment, in reality, is happening on the ground. All of that needs to be ready, included and working together as a system before you can declare any kind of operational capability.”

The four satellites launching Wednesday are nicknamed Anna, Ellen, Samuel and Tara, the names of children who won a European Commission painting competition.

The first stage of the Ariane 5 rocket set to loft the Galileo satellites will be fueled with cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen early Wednesday. The liquid-fueled upper stage’s load of toxic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide was pumped into the rocket last week, and the Ariane 5’s twin strap-on rocket boosters will burn pre-packed solid propellant.

After a series of weather, telemetry and other readiness checks by the Arianespace launch team, the countdown will commence an automated synchronized sequence at Minus-7 minutes. The computer-controlled final countdown will oversee pressurization of the rocket’s propellant tanks, final arming and other steps leading to ignition of the first stage’s Vulcain 2 main engine when the countdown clock reaches zero.

Seven seconds later, the launcher’s two solid rocket boosters will ignite to propel the Ariane 5 into the sky. The boosters’ nozzle steering systems will guide the Ariane 5 to the northeast, aligning with a trajectory that will carry the Galileo satellites between 56 degrees north and south latitude, the inclination range of the European navigation fleet.

Riding 2.9 million pounds of thrust, the Ariane 5 will exceed the speed of sound in less than a minute. Its twin solid rocket boosters will burn out and fall into the Atlantic Ocean at Plus+2 minutes, 19 seconds.

The Vulcain 2 main engine will continue firing until Plus+8 minutes, 56 seconds, then the Ariane 5’s core stage will drop away five seconds later.

The upper stage’s Aestus engine will ignite at Plus+9 minutes, 19 seconds, for the first of two burns required to inject the Galileo satellites into their high-altitude orbit.

Wednesday’s mission will be the final flight of the Aestus engine, which flies with the Ariane 5’s storable propellant upper stage, known by the French acronym EPS. The Aestus engine can be reignited in space and burns a toxic, but stable propellant mixture that can be stored for long durations, allowing the upper stage to operate for several hours after liftoff.

The rocket configuration launching Wednesday is known as the Ariane ES. The same version of the Ariane 5 has launched seven previous times, including five missions with Europe’s Automated Transfer Vehicle resupply ship for the International Space Station, and two flights carrying four Galileo satellites each in 2016 and 2017.

Wednesday’s launch will mark the 33rd flight of an Aestus engine on the Ariane 5 ES and previous Ariane 5 versions. The more commonly-used HM7B engine flown on the Ariane 5’s commercial satellite launches burns hydrogen and oxygen, and can only be started once in space.

All future launches of the Ariane 5 rocket, which will make its 99th liftoff Wednesday, will use the HM7B upper stage engine.

Ariane Group, which produces the Ariane rocket family and is majority owner of Arianespace, is developing a restartable cryogenic engine named Vinci to replace the HM7B on Europe’s new Ariane 6 rocket set for a maiden flight in mid-2020.

After its first cutoff at Plus+19 minutes, 58 seconds, the upper stage will coast more than three hours, climbing to an altitude of more than 14,000 miles before reigniting at 1452 GMT (10:52 a.m. EDT; 11:52 a.m. French Guiana time).

The second Aestus engine firing will last around six minutes, aiming for a circular orbit 14,243 miles (22,922 kilometers) above Earth.

The first pair of Galileo satellites will separate from the Ariane 5’s specially-designed dispenser at 1501 GMT (11:01 a.m. EDT; 12:01 p.m. EDT), followed by deployment of the second pair 20 minutes later.

Once in orbit, each of the 1,627-pound (738-kilogram) satellites will unfurl their power-generating solar panels. Ground controllers will command the spacecraft to raise their orbits by a few hundred miles to join Plane B of the Galileo constellation.

The satellites should be operational by January or February 2019 after a post-launch functional checkout, according to de Costa.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.