United Launch Alliance crews at Cape Canaveral are finishing final preparations for an Atlas 5 rocket launch Saturday evening to dispatch three U.S. military satellites directly to an orbital perch more than 20,000 miles over the equator.

Set for blastoff at 7:13 p.m. EDT (2313 GMT) Saturday, the Atlas 5 rocket will fly in its most powerful configuration, helped off Cape Canaveral’s Complex 41 launch pad with five Aerojet Rocketdyne-built solid rocket boosters and a Russian-made RD-180 main engine producing a combined 2.6 million pounds of thrust.

A military communications payload and a free-flying spacecraft hosting multiple Pentagon-funded experiments — including a deployable daughter satellite of its own — will ride the Atlas 5 rocket on a marathon six-hour mission to an altitude near geostationary orbit, the region over the equator where objects take advantage of orbital dynamics to hover over a fixed position on Earth.

The geostationary belt is populated by numerous data relay, missile warning and surveillance satellites operated by militaries and commercial companies.

Saturday’s launch window extends until 9:11 p.m. EDT (0111 GMT Sunday), according to an Air Force spokesperson, and there is an 80 percent chance of acceptable conditions for liftoff in the official launch forecast issued by the U.S. Air Force’s 45th Weather Squadron.

An approaching cold front will worsen weather conditions over Florida’s Space Coast on Sunday.

“On launch day, high pressure continues to migrate east as the aforementioned cold front advances into the Gulf Coast states in the morning and near the Florida Panhandle during the window,” the Air Force wrote in an outlook issued Friday morning. “Moisture is limited early in the count trending up gradually by the evening hours with the warm southerly winds. Diurnal heating will aid in developing limited isolated showers over Central Florida. No thunderstorms are expected.”

Forecasters predict gusty southeast winds Saturday evening, partly cloudy skies and isolated rain showers in the vicinity of Cape Canaveral. The temperature during the launch window will be around 77 degrees Fahrenheit, and the main weather concern for liftoff will be cumulus clouds.

If the launch is pushed back to Sunday, there is only a 20 percent chance of favorable weather, with widespread showers and thunderstorms in the forecast.

Ground teams transferred the Atlas 5 rocket to its launch pad Friday morning. The 197-foot-tall (60-meter) rocket rode a mobile launch platform from the Vertical Integration Facility to the Complex 41 launch pad, pushed by locomotives along rail tracks for the 1,800-foot (500-meter) journey.

Once firmly on the launch pad, the Atlas 5 and its mobile platform were scheduled to be plugged into ground propellant and electrical supplies. Workers planned to load RP-1 kerosene fuel in the Atlas 5’s first stage Friday afternoon in advance of Saturday’s countdown, which will kick off shortly after 12 p.m. EDT (1600 GMT).

The ULA launch team will power up the Atlas 5 rocket, test its telemetry transmitters, guidance system and range safety mechanisms, and fill the launcher’s Centaur upper stage with a cryogenic mixture of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. The first stage will also receive its supply of liquid oxygen, to be consumed with RP-1 fuel by the Atlas 5’s RD-180 main engine.

The countdown will have two built-in holds, and the final pre-planned pause at T-minus 4 minutes will give engineers time to catch up on last-minute troubleshooting and complete a poll of the launch team for approval to enter the terminal countdown sequence.

In the final four minutes of the countdown, the Atlas 5 will switch to internal power and pressurize its propellant tanks. A final status check is planned in the last 30 seconds before liftoff.

The rocket’s RD-180 main engine will ignite at T-minus 2.7 seconds, throttling up to 860,000 pounds of thrust before the Atlas 5’s five strap-on solid rocket boosters fire to send the launcher into the sky.

Heading nearly due east, the Atlas 5 will surpass the speed of sound in 34 seconds. The rocket’s five strap-on motors will empty their propellant casings and jettison in two groups beginning at T+plus 1 minute, 47 seconds.

The Atlas 5’s Swiss-made nose cone and a load-bearing structure around the rocket’s Centaur upper stage will separate around three-and-a-half minutes after liftoff. In the final phase of its burn, the RD-180 main engine will throttle back to limit acceleration on the Atlas 5’s satellite payloads, then switch off at T+plus 4 minutes, 33 seconds, in preparation for stage separation.

The Centaur stage’s RL10C-1 main engine will ignite at T+plus 4 minutes, 49 seconds, for a six-minute firing to reach a preliminary low-altitude parking orbit. Two more RL10 burns are planned, with the second maneuver starting at T+plus 22 minutes, 57 seconds, followed by a lengthy five-hour coast before the Centaur stage reignites to maneuver into a circular orbit slightly above geostationary altitude.

The rocket’s guidance computer will aim to reach an orbit approximately 24,200 miles (39,000 kilometers) over the equator, according to mission data released by ULA.

The Atlas 5’s two satellite passengers — the Continuous Broadband Augmented SATCOM spacecraft and a satellite known by the acronym EAGLE — will deploy from the Centaur upper stage approximately six hours after liftoff.

Saturday evening’s flight is the first time an unclassified Atlas 5 mission has placed geostationary payloads so close to their final orbital positions. Details of top secret missions for the National Reconnaissance Office, the U.S. government’s spy satellite agency, have not been disclosed.

The high-altitude deployment is in contrast to the mission profile for most satellites heading to geostationary orbit. In most cases, launchers release their payloads in an elliptical transfer orbit roughly a half-hour after liftoff, and the spacecraft must use on-board propellant to raise its altitude and null out its inclination to arrive on station over the equator.

A direct trip to geostationary orbit requires a long-duration coast and an engine restart after six hours in space, a capability used by ULA on multiple Delta 4 rocket flights.

Saturday’s flight, codenamed AFSPC 11, will be ULA’s fourth of 2018, and the third by an Atlas 5 rocket, which has logged 76 missions since 2002. It will be the eighth launch from Cape Canaveral since Jan. 1, including launches by ULA’s Atlas 5 and SpaceX’s Falcon rocket families.

AFSPC 11 is the 28th Atlas 5 mission for a branch of the U.S. military, and the 46th Atlas 5 launch with a U.S. national security payload. It is the eighth time an Atlas 5 rocket has flown in the launcher family’s most capable “551” version with five boosters, a five-meter fairing and a single-engine Centaur upper stage.

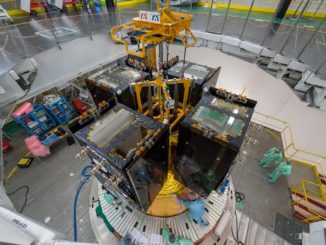

Three satellites are fastened inside the Atlas 5’s nose cone for Saturday’s launch

The upper payload is a military communications satellite named CBAS, short for Continuous Broadcast Augmenting SATCOM.

“CBAS is a military satellite communications spacecraft destined for geosynchronous orbit to provide communications relay capabilities to support senior leaders and combatant commanders,” the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center said in a statement. “CBAS will augment existing military satellite communications capabilities and broadcast military data continuously through space-based, satellite communications relay links.”

The Air Force kept the identity of the main payload on Saturday’s launch secret until April 6. An Air Force spokesperson declined to identify the contractor that built the CBAS satellite (pronounced “sea bass”), and the military released no further details on the mission.

“The Air Force issued the contract per standard Department of Defense acquisition practices in cooperation with defense industry partners,” the spokesperson said. “Per Department of Defense acquisition practices, details of the spacecraft source selection are not releasable.”

The lower passenger is the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) Secondary Payload Adapter (ESPA) Augmented Geosynchronous Laboratory Experiment satellite. The Air Force calls the nested acronym EAGLE for short.

Orbital ATK developed the EAGLE spacecraft by modifying a ring-like structure often used to connect small satellites to their launchers, adding solar panels, computers, rocket thrusters and instrumentation to the adapter. The Air Force says EAGLE will a pathfinder for future missions, demonstrating a maneuverable satellite design that could help the military launch new capabilities at less cost.

Managed by the Air Force Research Laboratory’s space vehicles directorate at Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico, the EAGLE mission “hosts experiments designed to detect, identify, and attribute threatening behavior as well as enhance Space Situational Awareness,” the Air Force said in a statement.

One of the experiments is a separating daughter satellite named Mycroft, apparently named for the older brother of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes. In one of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short stories, Sherlock Holmes says Mycroft possesses observational and deductive abilities greater than his own.

The Air Force describes Mycroft as a “fourth-generation space situational awareness experiment.” The service said the satellite will test technology that could be used by future missions to survey, catalog and inspect objects in geostationary orbit.

The Mycroft satellite, also built by Orbital ATK, “will explore ways to enhance space object characterization and navigation capabilities, it will investigate control mechansms used for flight safety, and it will explore the designs and data processing methods for enhancing space situational awareness,” the Air Force wrote in a fact sheet on the mission.

Mycroft is a follow-up to the Air Force’s ANGELS satellite, which launched into an orbit just above the geostationary belt in 2014 and ended its mission in November. ANGELS inspected the upper stage of its Delta 4 rocket soon after launch, then tested in-orbit surveillance, navigation and rendezvous operations for the rest of its mission.

According to the Air Force fact sheet, Mycroft will fly to a distance of around 21 miles (35 kilometers) from EAGLE, then re-approach the mother satellite to a range of about a kilometer, or 3,300 feet.

Mycroft will evaluate the region around the EAGLE satellite with an on-board camera, the Air Force said, and use its sensors and software to perform advanced guidance, navigation and control functions.

“The space domain is crucial today and will only increase in value moving into the future,” said Maj. Gen. William Cooley, commander of the Air Force Research Laboratory. “If the Air Force is to truly embrace space superiority then improving our ability to protect and defend vital space interests is of paramount importance.”

The Air Force said engineers have completed “rigorous research and development” to ensure Mycroft can safely fly through the congested geostationary orbit region.

Mycroft weighs a few hundred pounds, and its main body is no bigger than a mini-refrigerator, with a deployable solar panel out the side.

The Air Force owns four operational satellite sleuths in Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program. The GSSAP satellites flying around the same region as Mycroft and ANGELS more than 22,000 miles over the equator, feeding data on numerous foreign and commercial spacecraft movements positions to military officials.

The EAGLE satellite is scheduled to operate at least one year, and the Mycroft mission is expected to last 12 to 18 months, the Air Force said.

“Other experiments hosted on the EAGLE will detect, identify and analyze system threats such as man-made disturbances, space weather events or collisions with small meteorites,” the Air Force wrote in a fact sheet released Friday. “Together, EAGLE and Mycroft help train operators and development of tactics, techniques and procedures during exercises or experiments to improve space warfighting.”

The launch team at Cape Canaveral planned to send the CBAS and EAGLE mission skyward April 12, but last week delayed the flight to Saturday to replace a valve.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.