EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated April 13.

Orbital ATK’s bid to join the U.S. military’s roster of rockets to haul the most critical national security satellites into orbit faces stiff competition from entrenched launch providers and billionaire entrepreneurs, but the company is confident its Next Generation Launch system will win one of three funding agreements the Air Force is expected to award this summer.

The U.S. Air Force is preparing to select up to three companies later this year for Launch Services Agreements, the Pentagon’s name for cost-sharing public-private development contracts aimed at giving the military multiple launch options in the 2020s, all with U.S.-supplied booster propulsion systems.

Orbital ATK has launched orbital-class rockets more than 70 times, but the company’s biggest booster — the Antares — is sized for medium-size payloads, finding a niche in NASA’s program to deliver cargo to the International Space Station.

The solid-fueled Next Generation Launch system proposed by Orbital ATK would more than double the Antares rocket’s payload-carrying capability to most types of orbits, and enable Orbital ATK to place satellites into unique, harder-to-reach orbits that are currently not serviceable by any other launcher in the company’s fleet.

“We’re very confident that we’re going to receive selections for the next phase,” said Mike Laidley, Orbital ATK’s vice president of the Next Generation Launch program. “We think that we offer the Air Force a good opportunity to maintain their prime directive of assured access to space. We think solid motor propulsion has a place in this market, and we’re anxious to provide that.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Mike Laidley. Become a member today and support our coverage.

The new rocket would build on solid-fueled rocket motors Orbital ATK built for the space shuttle, but engineers have replaced the shuttle-era motor’s metallic casings with composite materials, reducing their weight and making the rockets easier to build.

“The key here is that there’s some automated winding equipment that’s going to make it more efficient for us, and it’s an opportunity to refine our processes and build these large 12-foot diameter segmented designs in a very efficient manner compared to the metal cases that were used in the shuttle era,” Laidley said.

United Launch Alliance, which was the only launch provider certified by the Air Force until 2015, is retiring most of the configurations in its Delta 4 rocket family in 2019, followed by the phase-out of the Delta 4-Heavy version in the early or mid-2020s. The company says the Delta 4 is no longer competitive on cost.

ULA’s Atlas 5 will be replaced by the Vulcan rocket in the early 2020s, a two-stage launcher that will use U.S.-made engines. This Atlas 5, which is less expensive than the Delta 4, currently uses Russian-made RD-180 engines.

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket is the other major player in today’s national security launch market. Since its certification by the Air Force in 2015, the Falcon 9 has won contracts to launch five GPS navigation satellites, and is in the running for more military launch deals.

The Falcon Heavy rocket, which flies with three modified Falcon 9 rocket boosters bolted together, is not yet eligible to launch the military’s most expensive space missions. That certification will come once the Falcon Heavy accrues multiple successful flights, and goes through a detailed Air Force engineering review.

Orbital ATK is a newcomer to the market for launching large military communications, navigation and reconnaissance satellites. But Laidley says the company’s Next Generation Launch system, which uses solid-fueled first and stage stage motors topped with a cryogenic liquid-fueled upper stage, is a solution the Air Force should consider.

“We’ve been working to develop a launch system that would support those EELV (Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle) mission requirements — all the different launch payload types and orbits,” Laidley said. “We’ve been working on that now for about two-and-a-half years.”

The Air Force awarded funding in 2016 to ULA, SpaceX, Orbital ATK and Aerojet Rocketdyne to work on U.S.-made propulsion technology to power new rockets, eyeing a replacement to the Russian RD-180 engine. The funding agreements required the companies to put forward some of their own money in the effort.

ULA directed much of its funding toward Blue Origin, the space company founded by Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos which is testing the BE-4 engine fueled by liquified natural gas. ULA says Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine is their preferred option to power the Vulcan rocket’s first stage. SpaceX’s slice of the Air Force engine money went toward the company’s Raptor engine, a methane-fueled powerplant for a huge new rocket named the BFR, or Big Falcon Rocket.

Orbital ATK focused its funding on the Next Generation Launch system, while Aerojet Rocketdyne — an engine-builder, not a rocket operator — advanced the design of its AR1 engine, which ULA is keeping as a backup option for the Vulcan launcher in case the BE-4 runs into trouble.

Blue Origin received some Air Force propulsion funding routed through ULA for the BE-4 engine, but the lion’s share of the company’s engine development has been privately-funded.

The Air Force released a follow-up request for proposals in October, seeking bids for government funding to help launch companies pay for their next-generation rockets through the military’s EELV program. The Launch Services Agreements will be announced in the next few months to fund continued work on up to three launch vehicles, followed by a down-select to two providers in late 2019.

Those two finalists will continue receiving government funding support through their rockets’ test flights.

ULA, SpaceX and Blue Origin are expected to compete for Launch Services Agreements.

Blue Origin’s chief executive, Bob Smith, said last year the company is in early talks with the Air Force about certifying its own New Glenn rocket for national security missions, potentially placing Blue Origin in competition with ULA, one of its customers. An industry official familiar with matter said Thursday that Blue Origin has submitted a proposal for an Air Force Launch Services Agreement.

Lacking the financial backing and personality of a billionaire entrepreneur like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos, Orbital ATK is flying under the radar. But the company received news earlier this year that keeps it in the competition.

Laidley said the Air Force informed Orbital ATK in February that the Next Generation Launch system proposal was within the “competitive range,” and is eligible for further scrutiny leading up to a potential contract award.

“We’ve invested a lot of our money to date, so it was important for the Air Force to evaluate our proposal and say that it’s adequate, and now any money we spend can ultimately be counted toward the cost share investment in the Launch Services Agreement,” Laidley said in a recent interview with Spaceflight Now.

Orbital ATK said in January that the company and the Air Force have jointly invested more than $200 million on the NGL program.

Laidley declined to how much of Orbital ATK’s own money has been applied to the NGL program, but the terms of the Air Force’s 2016 funding agreement to support development the new rocket’s solid-fueled propulsion system said the Air Force would supply between $46.9 million and $180.2 million for the program’s first phase, with Orbital ATK pledging between $31.1 million and $124.8 million.

The Air Force requires that companies provide at least one-third of the development cost through internal funding.

“We’re providing more than the minimum, but it’s competitive, so we’re not prepared to talk about our negotiation strategy,” Laidley said.

Laidley also declined to provide cost estimates for an individual NGL mission.

“We will certainly be competitive,” he said. “We took a hard look at what those missions have sold for historically, and we can be competitive in that marketplace.

“One of the opportunties we’ve got that others don’t is we do have our own in-house supply of customers. We produce our own satellites. We buy launch services. We’ve historically bought launch services from both of these competitors that are currently in play. We have an in-house opportunity to capture work from our own team, and that makes us unique as well.”

Orbital ATK says the Next Generation Launch system will benefit from upgraded avionics, computers and other technology based on components already used on the company’s smaller rockets.

“We’ve got avionics that we’ve developed in-house in our launch vehicle division, and those avionics fly in all of our launch vehicle products, from our small targets that we sell to the Navy, all the way up to Antares,” Laidley said. “As part of the NGL effort, we’re developing a fault-tolerant version of those avionics, which basically involves taking multiple sets of software voting logic … That gives the Air Force a lot of confidence that we have a system that’s got a solid flight history.”

If Orbital ATK wins additional Air Force funding this summer, Laidley said engineers will advance the design of the entire rocket, which has so far been limited to funding from the company’s own coffers. The Air Force money already awarded to Orbital ATK could only be used on developing the NGL system’s Common Booster Segment, derivatives of which would power the rocket’s first and second stages.

“That was restricted to developing primary propulsion products that would support the RD-180 replacement,” he said of the existing Air Force funding award. “The LSA (Launch Services Agreement) money, we need to use it for the launch system or the launch system infrastructure. It’s geared toward putting together an overall launch system. It’s not restricted to the use of any particular stage. We will use the cost-share money to fund the entire system.”

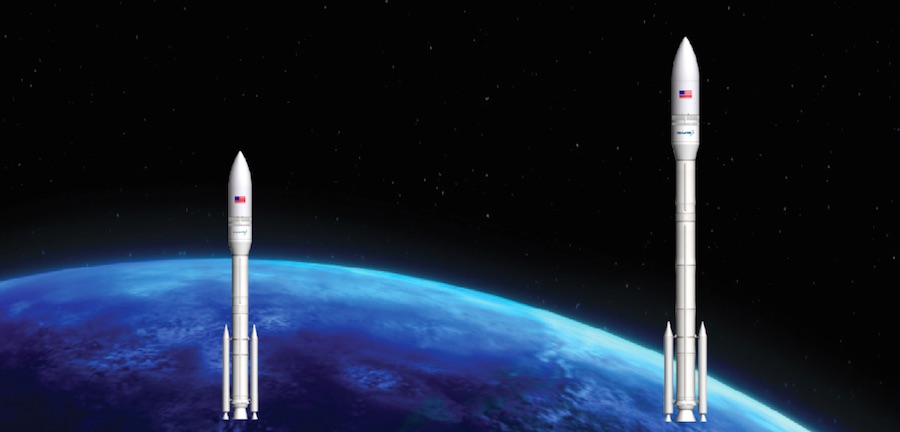

The NGL would come in two basic versions: an intermediate and a heavy configuration.

The intermediate version would have a two-segment solid-fueled core stage, called a Castor 600, that would generate 2.1 million pounds of thrust at liftoff. The heavy version would have a four-segment core rocket motor, the Castor 1200, putting out 3.1 million pounds of thrust.

Both configurations would have a single-segment Castor 300 second stage motor, built using the same tooling as the multi-segment first stage motors, and a hydrogen-fueled cryogenic upper stage engine. The Castor motors would be produced and tested at Orbital ATK’s facility in Promontory, Utah.

“As we start through this process, we built these segmented cases so we can do loads testing, burst testing, and use them to develop our manufacturing processes for winding insulation and ultimately pouring the overall motors,” Laidley said. “All of this is leading up to static fire testing of the first two stages of the intermediate class, what we’re calling the Castor 600, which is a two-segment first stage, and the Castor 300, a single-segment second stage. Those motors will static fire in 2019.”

The intermediate and heavy configurations could get an additional boost from up to six strap-on boosters, the same 63-inch diameter augmentation motors Orbital ATK is currently qualifying for use on ULA’s Atlas 5 and Vulcan rockets. The number of strap-on boosters on each NGL flight could be tailored based on mission requirements, allowing for odd numbers boosters to fly on the rocket, similar to the Atlas 5’s design, Laidley said.

The solid rocket boosters, known as GEM 63XLs, would remain attached to the NGL’s first stage in the intermediate version, then jettison together with the core motor. The boosters would separate individually on the heavy version, Laidley said.

Laidley said Orbital ATK has studied proposals for third stage engines from Blue Origin, Aerojet Rocketdyne and Europe’s Ariane Group. A final decision on the NGL’s upper stage engine is expected soon.

Orbital ATK plans to build the launcher’s 5-meter (16-foot) diameter payload shroud — roughly the same diameter as fairings flown on Atlas 5, Falcon 9 and Ariane 5 rockets — at the company’s structures division in Iuka, Mississippi.

According to an Orbital ATK fact sheet, the intermediate version of NGL will lift between 10,800 pounds (4,900 kilograms) and around 22,300 pounds (10,100 kilograms) into a geostationary transfer orbit, an elliptical loop around Earth commonly by communications satellites transiting to geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator.

That performance range is comparable to the lift capacity of ULA’s Atlas 5 rocket family.

The heavy NGL configuration can loft between roughly 11,600 pounds (5,250 kilograms) and 17,200 pounds (7,800 kilograms) of payload directly into geostationary orbit — eliminating the need for a spacecraft to use its own fuel for major orbital maneuvers.

The NGL’s exact performance capability depends on the number of solid-fueled boosters added to the rocket.

“Right now, we’re planning on about three to four missions per year to close our business case,” Laidley said. “A couple of those could come from the Air Force and a couple of those could come from either our internal needs or the commercial community. We can close our business case with a fairly low launch rate, and that’s primarily due to the diversity of our business base, and the fact that right now we’ve got a number of other large programs in our launch vehicle division, along with the propulsion systems division and aerospace structures.”

Orbital ATK does not plan to reuse any parts of the NGL system, despite the company’s history with refurbishing shuttle solid rocket boosters.

“We’re not planning any reusability in this vehicle,” Laidley said. “We’re really focusing on commonality with our other product lines and getting as efficient as we can that way.”

Some of the savings, Laidley said, were realized by the merger of Orbital Sciences and ATK in early 2015. The corporate marriage brought together ATK’s experience with solid rocket propulsion and composite structures and Orbital’s knowledge of launch vehicle and satellite manufacturing and operations.

“Without the merger, it would have been very difficult to pull this together, with hardware coming from different companies,” Laidley said. “It would have been very difficult for us to be competitive. We think NGL is the first major offering that allows us to leverage all the capabilities of the company that our corporate leaders envisioned.”

Orbital ATK’s expected acquisition by Northrop Grumman should not affect the new rocket’s development, according to Laidley.

“We firmly believe the new ownership is committed,” he said. “They’ve expressed their interest in this as well. I think this is a program area that they would use as a growth area.”

Assuming Orbital ATK receives the next two tranches of Air Force funding, the intermediate version of the NGL system could make its maiden flight from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida in the first quarter of 2021, Laidley said. After as few as two successful test missions, the rocket could be certified by the Air Force for national security payloads by the end of 2021.

The heavy version would follow with two test flights in 2024.

“The proposal we submitted gives the government a firm cost and cost-share proposal all the way through the intermediate and heavy certification flight,” Laidley said.

Orbital ATK has secured an agreement with NASA to use Mobile Launch Platform No. 3, originally built for the Saturn 5 moon rocket and modified for the space shuttle, for NGL missions. Technicians would stack the rocket inside High Bay 2 in the cavernous Vehicle Assembly Building, then roll out to launch pad 39B a few days before liftoff.

Final details of the agreement to provide for Orbital ATK’s co-use of pad 39B with NASA’s Space Launch System are being worked out now, Laidley said.

Construction to ready the launch platform and VAB high bay for Orbital ATK’s rocket could begin next year, contingent on the Next Generation Launch system’s green light from the Air Force this summer.

For a West Coast launch site to support polar orbit missions, Orbital ATK is considering at least two options: Upgrading the Delta 2 launch pad at Space Launch Complex 2-West once that rocket is retired later this year, or moving into Space Launch Complex-6 when the Delta 4-Heavy flies its last mission in the 2020s.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.