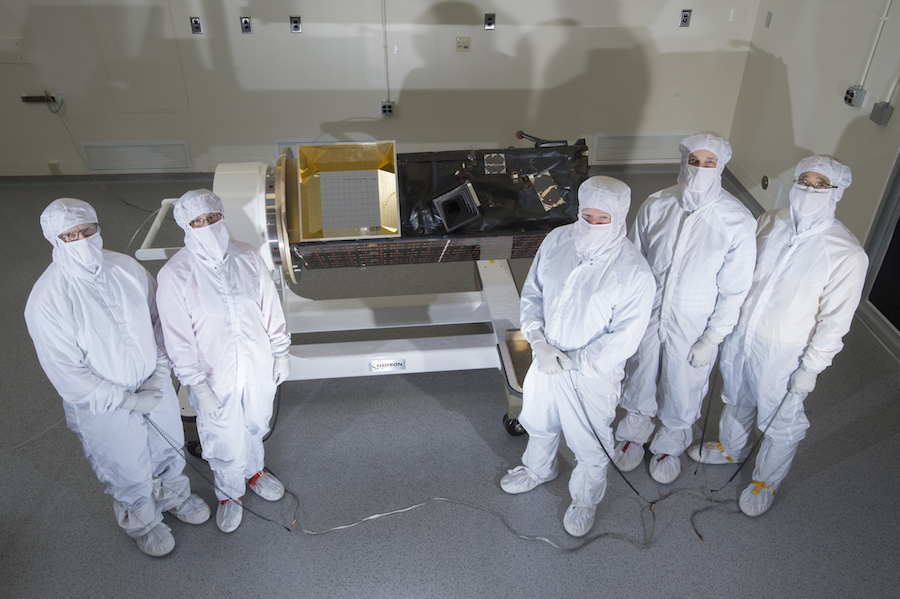

A U.S. military satellite awaiting launch Friday night from Cape Canaveral is small enough to fit on a coffee table, but it will punch above its weight, scanning a region more than 20,000 miles above Earth to catalog spacecraft movements and space junk.

The 249-pound (113-kilogram) spacecraft carries a telescope and a camera to locate and help track objects in geosynchronous orbit, a belt thousands of miles over the equator home to commercial and military communications, surveillance and weather satellites.

Developed by the military’s Operationally Responsive Space office, the spacecraft fills a looming data gap expected once the Air Force’s current Space Based Space Surveillance Block 10 satellite ends its mission, and before a follow-on program is ready for liftoff.

Named ORS-5, or SensorSat, the spacecraft will ride a Minotaur 4 rocket into orbit from Complex 46, a long-dormant launch pad located near the eastern tip of Cape Canaveral.

A four-hour launch window opens at 11:15 p.m. EDT Friday (0315 GMT Saturday).

Forecasters from the Air Force’s 45th Weather Squadron predict a 60 percent chance conditions will be acceptable for liftoff Friday night. Their primary worry is with cumulus and thick clouds over the launch site influenced by a nearby tropical wave.

The five-stage booster is comprised of three modified solid-fueled rocket motors from the Air Force’s decommissioned Peacekeeper missile stockpile, and two commercially-produced stages to inject the ORS-5 satellite into orbit.

Friday night’s launch will be the first Minotaur flight from Cape Canaveral. Fifteen previous Minotaur missions, all using retired Minuteman or Peacekeeper missile parts, have launched satellites into orbit from pads in California, Virginia and Alaska.

The $87.5 million ORS-5 mission is the latest in a line of relatively low-cost military projects managed by the ORS office. Previous ORS missions have tested plug-and-play satellite technology, deployed experimental imaging and data relay satellites, and demonstrated an autonomous rocket destruct mechanism now used on commercial launchers.

Air Force Col. Shahnaz Punjani, director of the ORS office, compared the ORS-5 satellite’s function to the A-10 attack jet, an aircraft that carries a powerful armor-piercing cannon.

“When people talk about the A-10 aircraft, (they say) it’s really a gun with an airplane wrapped around it,” Punjani said. “In this case, the ORS-5 satellite is essentially a telescope in low Earth orbit with a spacecraft wrapped around it, looking at the geosynchronous belt.”

Another way to look at it is to compare the ORS-5 satellite to an airport radar, said Grant Stokes, head of the space systems and technology division of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory, where the spacecraft was developed and manufactured.

“It’s sort of analogous to a surveillance radar at an airport, which goes around and around, surveilling the domain,” Stokes told reporters in a prelaunch briefing Thursday. “Once per orbit, what ORS-5 will do is scan the GEO (geosynchronous) belt and keep track, essentially, of all the items there.

“The GEO belt is particularly important,” Stokes said. “There’s a huge collection of satellites there, and a tremendous amount of economic value in that special orbit, so it is one that generally we want to keep fairly good tabs on what’s there and where things are.”

Satellites in geosynchronous orbit nearly 22,300 miles (35,800 kilometers) above the equator fly around Earth at the same rate the planet rotates. The effect at that altitude keeps satellites over the same geographic position at all times.

Designed for a three-year mission, ORS-5 should feed military officials data on how objects are moving around geosynchronous orbit. After identifying which objects might be threats, the Air Force could task the more capable SBSS Block 10 satellite to take better pictures, or send one of the military’s four close-up inspection satellites in geosynchronous orbit to take a closer look, according to Lt. Col. Heather Bogstie, ORS-5 program manager.

The data output from ORS-5 “gives you dots on a screen,” Stokes said.

“We very carefully measure how bright they are, but it does not resolve in any way,” he said. “It’s a dot at a distance of something like 40,000 kilometers (nearly 25,000 miles).”

Punjani said the ORS-5 satellite is a “change detection agent” to collect imagery of broad swaths of space. In keeping with the ORS program’s low-cost ethos, the ORS-5 mission was conceived to meet minimum standards required by the military’s space surveillance division, without the bells and whistles on more expensive spacecraft.

The SBSS Block 10 satellite launched in September 2010 cost more than $800 million, around 10 times more than ORS-5.

SBSS Block 10 will exceed its seven-year design life later this year, and a full-up replacement satellite is not expected to launch until at least 2021.

“When you look at how ORS builds our satellites, we’re going to go small,” Punjani said. “We’re going to go to threshold requirements, and then we’re going to hold to those requirements and not change those requirements throughout the life cycle, in order to ensure we rapidly acquire these programs. This program was done within three years, compared to other satellite programs that have a five-to-ten year life cycle.”

The Air Force said the ORS-5 satellite itself cost around $49 million. Another $27.2 million went toward purchasing the Minotaur 4 launch from Orbital ATK, the rocket’s commercial operator, and ground systems cost $11.3 million.

The military needed a dedicated rocket for the ORS-5 mission because of its unique orbit 372 miles (600 kilometers) directly over the equator. That type of orbit required the Air Force and Orbital ATK to base the launch from Cape Canaveral instead of from an already-used Minotaur pad at Wallops Island, Virginia.

Officials looked at several launch options, including building a temporary Minotaur launch pad at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, or at the European-run Guiana Space Center in South America.

The cheapest and least risky option ended up being an uprated Minotaur 4 rocket launched from Cape Canaveral.

The Minotaur 4 usually comes with four stages, but the ORS-5 satellite’s equator-hugging orbit needed an extra boost. Instead of flying with a single Orion 38 rocket motor on top of the Peacekeeper missile stack, Friday night’s launch will carry two Orion 38 stages.

It was a case of necessity breeding invention, officials said.

The Minotaur 4, which stands about eight stories tall, will take off from pad 46, a complex which last hosted a launch in 1999. Space Florida, an arm of the state government, paid $6.6 million to refurbish the launch pad for the ORS-5 mission and future launch opportunities, according to Jim Kuzma, Space Florida’s chief operating officer.

Heading east from Florida’s Space Coast, the Minotaur 4 will race into the sky on top of a half-million pounds of thrust before dropping its Peacekeeper first stage into the Atlantic Ocean about a minute after liftoff.

Two more Peacekeeper motors will fire back-to-back until T+plus 3 minutes, 17 seconds. The Minotaur’s nose cone will jettison during the third stage burn once the rocket flies into space.

The three Peacekeeper rocket stages were originally manufactured and packed with solid fuel in the 1980s. The motors launching Friday are 28, 29 and 30 years old, according to Lt. Col. Chad Melone, division chief of the Space and Missile Systems Center’s launch enterprise services directorate.

The motors were stored at Hill Air Force Base in Utah until they were pulled from the military’s stockpile. Technicians repainted the rocket stages and handed them over to Orbital ATK, which installed avionics and other equipment to make them ready for a satellite launch.

The Minotaur’s Orion 38 fourth stage will ignite around 14 minutes into the flight, burning for approximately one minute to reach an elliptical, oval-shaped orbit ranging in altitude between 248 miles and 372 miles (400-600 kilometers). The temporary parking orbit will have a tilt of 24.5 degrees to the equator.

Three CubeSats will release from the Minotaur rocket beginning about 17 minutes after launch.

The secondary payloads include two 1.5-unit CubeSats, weighing around 3.3 pounds (1.5 kilograms) each, from Los Alamos National Laboratory. A larger shoebox-sized CubeSat from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, with a weight around 6.6 pounds (3 kilograms) is also hitching a ride.

Soon after the CubeSat deployments, the fourth and fifth stages of the Minotaur 4 will detach. The final Orion 38 stage will fire for a little more than a minute to circularize ORS-5’s orbit at 372 miles and steer it onto a course that stays over the equator.

Separation of the ORS-5 satellite from the Minotaur 4 rocket is expected at T+plus 28 minutes, 28 seconds.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.