Updated at 1 p.m. EDT (1700 GMT) May 16 with orbit figures.

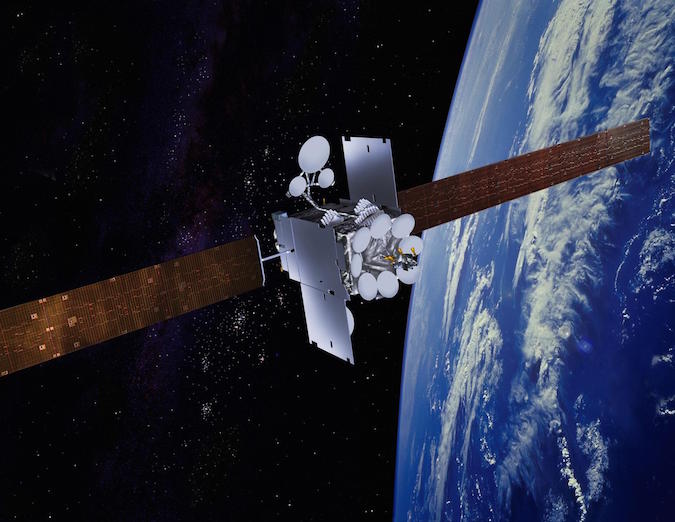

A Boeing-built satellite on the way to join Inmarsat’s globe-spanning network geared to beam Internet and data transmission capacity to airline passengers, maritime crews and military personnel flew into orbit Monday from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida aboard an expendable Falcon 9 rocket.

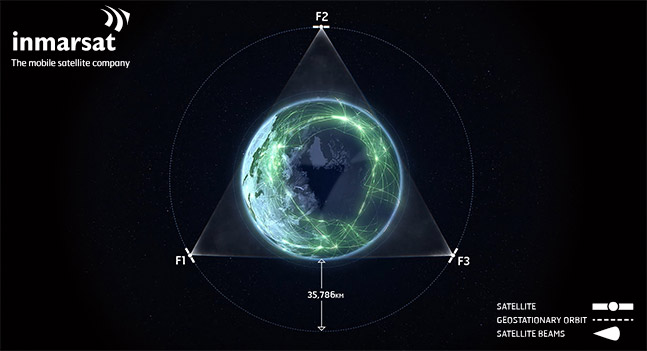

The satellite is the fourth member of Inmarsat’s broadband communications fleet, a $1.6 billion initiative named Global Xpress conceived to connect aircraft, ships at sea, and mobile users on land through an umbrella of worldwide Ka-band beams.

The two-stage rocket, towering 229 feet (70 meters) tall, was stripped of recovery hardware to give the 6.7-ton Inmarsat 5 F4 payload the boost it needed toward an eventual circular geostationary orbit 22,300 miles (35,800 kilometers) over the equator.

The Falcon 9 booster ignited its nine Merlin 1D main engines in the last three seconds of a smooth countdown, passed a computer health check, and soared skyward from launch pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 7:21 p.m. EDT (2321 GMT).

Generating 1.7 million pounds of thrust, the nine kerosene-fueled main engines propelled the Falcon 9 toward the east into a cloud-free blue sky, trailing a plume of fiery exhaust as it exceeded the speed of sound and left a rumble in its wake across Florida’s Space Coast.

The first stage engines turned off around T+plus 2 minutes, 45 seconds, and the booster stage detached to fall into the Atlantic Ocean on a destructive plunge. The heavy weight of the Inmarsat 5 F4 satellite, which weighed 13,417 pounds (6,086 kilograms) at liftoff, required all of the Falcon 9’s energy, leaving no propellant left over for the first stage to slow down for a landing.

SpaceX normally guides its Falcon 9 first stages toward landing targets at Cape Canaveral or offshore in the ocean in a bid to refurbish and reuse the boosters.

The launcher’s single second stage engine ignited moments after the booster fell away at an altitude of around 50 miles (80 kilometers), firing for nearly six minutes to inject the Inmarsat 5 F4 satellite into a preliminary parking orbit. The Falcon 9’s composite payload fairing dropped away from the rocket during the second stage engine burn.

The battery-powered second stage shut down its Merlin engine, raced across the Atlantic at a speed of nearly 5 miles (8 kilometers) per second, and then reignited as it crossed the equator over the Gulf of Guinea.

The nearly minute-long engine firing was designed to send Inmarsat 5 F4 into an arcing “supersynchronous” transfer orbit, an egg-shaped loop around Earth with its highest point at an altitude of several tens of thousands of miles. Publicly-available tracking data from the U.S. military indicated Inmarsat 5 F4 was delivered into an elliptical orbit ranging from 236 miles (381 kilometers) to 43,395 miles (68,839 kilometers) in altitude, tilted 24.5 degrees to the equator.

Instead, the engine was programmed to fire as long as possible, draining almost all of the propellant from the upper stage’s tanks to place Inmarsat 5 F4 into the highest orbit possible.

SpaceX confirmed the rocket reached a good orbit, and the upper stage released the Inmarsat spacecraft just shy of the flight’s 32-minute point.

Inmarsat said the new satellite radioed its status to engineers via a ground station in Perth, Australia, at 8:04 p.m. EDT (0004 GMT), verifying the spacecraft was alive and healthy following Monday evening’s blastoff.

The on-target deployment gave SpaceX its second successful launch in two weeks, after a Falcon 9 rocketed into orbit with a top secret U.S. government spy payload May 1.

More than a half-dozen burns by the satellite’s on-board propulsion system are planned over the next 10 days or so, followed by extension of Inmarsat 5 F4’s power-generating solar panels May 28 to a span of 133 feet (more than 40 meters), wider than the wingspan of a Boeing 737 passenger jet.

Then the satellite’s xenon-ion maneuvering jets will take over to fine-tune its path around Earth, settling in a circular orbit directly over Earth’s equator by mid-August, and perhaps sooner if the Falcon 9 placed it into an optimum orbit. The spacecraft will go into a geostationary-type orbit, flying around the planet at the same speed as Earth’s rotation, ensuring the satellite remains over a fixed geographic position.

Inmarsat 5 F4 should be operational around the end of this year, and its first job will likely be to grow Inmarsat’s broadband network load over Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and the Indian subcontinent, according to Michele Franci, Inmarsat’s chief technology officer.

“It’s for passenger connectivity, so it’s wifi services for passengers for web browsing, email, video downloads and uploads,” Franci said of the Global Xpress network. “On ships, our biggest market today is in merchant shipping, and there it will provide a combination of operational services and crew welfare.”

Inmarsat 5 F4 joins three nearly identical satellites, all based on the Boeing 702HP spacecraft bus, launched by Russian Proton rockets from 2013 through 2015. The first Inmarsat 5-series satellite entered service over Europe, the Middle East and Africa, the second covers the Atlantic Ocean and the Americas, and a third Inmarsat 5 satellite launched in August 2015 provides coverage to the Asia-Pacific and Australia.

Each Inmarsat 5-series Global Xpress satellite carries 89 fixed and six steerable spot beams in Ka-band. The company’s earlier satellites broadcast in L-band, but Inmarsat switched to Ka-band for the Global Xpress system, offering improved downlink communications speeds to 50 megabits per second, with up to 5 megabits per second on the uplink side.

The jump in throughput with Global Xpress has attracted airlines and maritime operators to Inmarsat.

According to Franci, around 1,000 ships already use Global Xpress services.

“The system is working steady, even though we’re still in the introductory phase, but we are already seeing that in many areas there is going to be concentration of traffic,” he said.

Rupert Pearce, Inmarsat’s CEO, said May 4 that Global Xpress is now in full commercial service providing passenger broadband connectivity on 80 aircraft operated by Lufthansa, Austrian Airlines and Swiss International Air Lines. The German low-cost carrier Eurowings will start using Global Xpress in a few weeks, he said.

Inmarsat also has an agreement to add Global Xpress receivers to aircraft owned by the Malaysian airline AirAsia, and Qatar Airways has announced it intends to install Global Xpress for in-flight wifi on its long-haul planes.

Boeing is responsible for selling military-grade Global Xpress Ka-band services to U.S. government and military users.

Established in 1979 to supply emergency satellite-based communications for maritime vessels, Inmarsat has expanded to become a leader in linking on-the-go consumers. The Global Xpress fleet is tailored to connect with passengers and crew on fast-moving airplanes, freighters in the open ocean, military units on battlefields and remote oil and gas industry operators.

Originally manufactured as a spare, Inmarsat 5 F4 will add more throughout to the Global Xpress network, and Inmarsat could relocate the satellite during its life to cover different regions.

“Whether it’s going to stay (over Europe) for long — long meaning most of its life — or not, that will depend on the other deployments we’re doing and the market demand,” Franci said. “But right now, that’s the area we expect to initially deploy it.”

“Because it’s not needed (for) complete global coverage, the role of Inmarsat 5 F4 could change through its life,” said Tony Bates, Inmarsat’s chief financial officer, in a May 4 quarterly conference call with investment analysts. “And obviously, they are for in-orbit redundancy, which would limit it if it was needed for that purpose. But otherwise, it can go off to discrete business opportunities that may differ during its life.”

Inmarsat originally booked Inmarsat 5 F4 for a launch on SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket, but delays in the debut of the new commercial mega-booster prompted a switch to the smaller Falcon 9 to avoid a “very significant delay,” Franci said.

Inmarsat also moved another satellite off the Falcon Heavy last year, booking it on an Ariane 5 rocket launch from SpaceX rival Arianespace. That spacecraft, owned in partnership by Inmarsat and Greece’s Hellas-Sat, will lift off June 28 from French Guiana.

Franci said Inmarsat has contract options to launch more satellites with SpaceX in the future, but no firm payload assignments have been made.

Monday’s launch debuted an upgrade to the Falcon 9 rocket’s second stage intended to speed up fueling during launch countdowns, allowing liquid oxygen and helium pressurant to be simultaneously loaded into the launcher.

Investigators blamed a Falcon 9 rocket explosion at Cape Canaveral’s pad 40 last September on voids in the skin of high-pressure helium tanks immersed in super-cold liquid oxygen inside the launcher’s second stage. Liquid oxygen became trapped, and perhaps froze, in the openings, leading to friction that eventually caused the rocket to explode, destroying an Israeli-owned communications satellite during a countdown rehearsal.

After an engineering inquiry settled on a probable cause for the mishap, SpaceX said future countdown sequences would change to load helium into the rocket before liquid oxygen, a modification the company said would avoid the problem. At the same time, SpaceX said it would make hardware changes to the rocket to permanently fix the helium tank concern.

Those unspecified safety upgrades made their way into the Falcon 9 that launched Monday.

A SpaceX official said the next two Falcon 9 flights in June will not have the helium tank modification, but then all future rockets will incorporate the change.

SpaceX ground crews are preparing for four more launches by the end of June, with the next Falcon 9 flight slated for June 1 with a Dragon supply ship to ferry experiments and equipment to the International Space Station. Liftoff of the Dragon capsule — the first SpaceX cargo craft to be reused after a previous space station mission — is scheduled for approximately 5:55 p.m. EDT (2155 GMT) June 1 from pad 39A.

Another Falcon 9 rocket is being primed for blastoff from the Kennedy Space Center on June 15 with BulgariaSat 1, Bulgaria’s first communications satellite. That launcher will fly with a previously-used first stage, the second time SpaceX will have re-flown a Falcon 9 booster.

Two more Falcon 9 missions in late June will launch from the Kennedy Space Center and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

The Intelsat 35e telecom satellite, a trans-Atlantic video, data and broadband relay station, has a launch window some time between June 26 and July 2 from Florida, an Intelsat spokesperson said Monday.

The second batch of 10 next-generation satellites for Iridium’s mobile telephone and data messaging constellation is supposed to launch June 29 from California.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.