Four satellites fastened to the top of an Ariane 5 rocket will grow Europe’s space-based Galileo navigation network Thursday morning with a launch from the South American jungle.

The spacecraft will ride a specially-modified Ariane 5 launcher to an orbital perch more than 14,000 miles (about 23,000 kilometers) above Earth, but it will take nearly four hours for the rocket’s hydrazine-fueled second stage to put the four Galileo satellites into their high-altitude home.

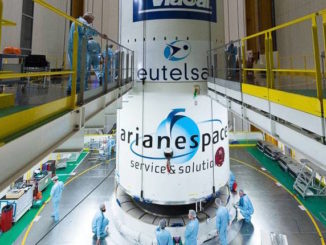

Ground crews rolled the Ariane 5 rocket out of its final assembly building Tuesday morning for the 1.7-mile (2.7-kilometer) trip to the ELA-3 launch zone at the Guiana Space Center. Once the rocket arrived at the pad, technicians prepped the launcher for the final countdown by loading liquid helium pressurant into the Ariane 5’s core stage and heating up fuel tanks on the upper stage, a step made necessary by the long-duration flight planned Thursday.

Liftoff is set for 1306:48 GMT (8:06:48 a.m. EST; 10:06:48 a.m. local time in French Guiana) Thursday to kick off the sixth Ariane 5 flight of the year, and the rocket’s 89th mission overall since its debut in 1996.

The four satellites riding to space Thursday will give Europe’s Galileo global positioning fleet 18 spacecraft, three-quarters the number needed to provide worldwide location and timing coverage independent of long-lived navigation networks like the U.S. Air Force’s Global Positioning System and Russia’s Glonass constellation.

The multibillion-dollar Galileo program, run the European Commission, aims to be a civilian-operated alternative to the military-run satellite navigation programs in the United States and Russia. Combined with the GPS and Glonass satellites, the Galileo fleet will give users equipped with compatible handsets even better positioning than possible today, especially in rugged terrain and in large cities where skyscrapers can block satellite signals from reaching the ground.

The first 14 satellites launched two at a time aboard Russian Soyuz rockets from French Guiana, and Thursday’s launch is the first of at least three Ariane 5 flights dedicated to the Galileo program over the next two years.

Another Ariane 5 launch in 2017 will loft four more Galileo satellites, followed by a third Ariane 5 mission for the strategic navigation program as soon as 2018.

Thursday’s launch will target Plane C of the Galileo constellation, which is spread among three orbital pathways. Each of the planes will be populated by eight active satellites, plus two spares, when the Galileo fleet is completed around 2020.

The Ariane 5 will steer toward the northeast from the French Guiana coastline and soar over the Atlantic Ocean, passing above a ship-based tracking station and a communications site in the Azores, then sail over Europe as it climbs up to target altitude.

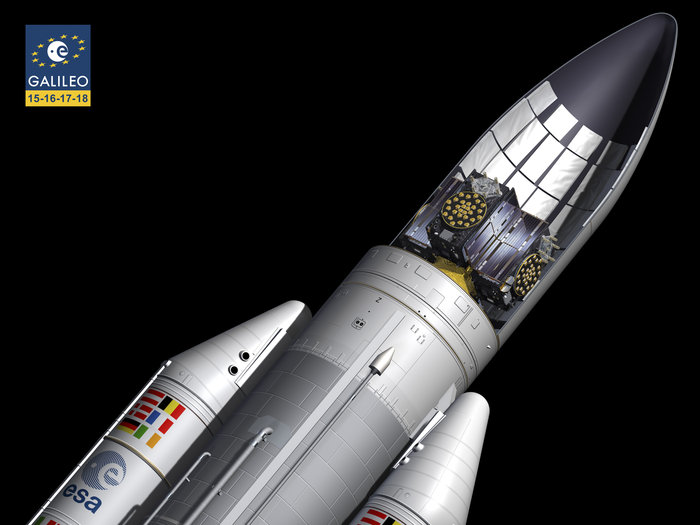

“The uniqueness of this launch is that we start, for the first time, with an Ariane 5,” said Paul Verhoef, director of navigation at the European Space Agency, which assists the European Commission, the EU’s executive body, with the deployment of the Galileo satellites. “Ariane 5 has been specifically modified. It is a specific verison which is only going to be used for Galileo. On top of it we have a so-called dispsener, which is a device to which the the four satellites are hanging during the launch.”

The dispenser was made by Airbus Defense and Space and tested at the company’s facilities in Bordeaux, France, before engineers signed off on its first use with this week’s launch.

The launcher version designed for Galileo missions also features a shortened nose cone enclosing the satellites, and a lightened Vehicle Equipment Bay structure compared to previous Ariane 5 ES flights, which carried heavy 20-ton Automated Transfer Vehicles on cargo runs to the International Space Station.

The Galileo satellites, manufactured in Germany by OHB System and outfitted with British-made navigation payloads from SSTL, are lighter and put less of a load on the Ariane 5’s structure.

Engineers also introduced electrical and thermal modifications to allow the upper stage to coast for more than three hours between engine burns — a first for the Ariane 5 and a requirement to inject the Galileo satellites close to their final operational orbits more than 14,000 miles above Earth.

The basic core stage and its Vulcain 2 engine, along with the Ariane 5’s powerful solid rocket boosters, are unchanged with Thursday’s launch, but the rocket will fly with a older-model upper stage with storable hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants to replace the more commonly-used hydrogen-fueled upper stage engine.

The HM7B engine normally flown on Ariane 5 rockets can only be started once after launch, whereas the Aestus engine on the storable propellant stage can ignite multiple times in flight.

That capability is needed Thursday, when the Aestus engine will first fire to reach an egg-shaped transfer orbit, then shut down to coast up to the Galileo fleet’s operating altitude. Once there, the engine will ignite again to circularize the orbit before letting go of the four satellites on-board.

The satellites will spring away from the dispenser in pairs at T+plus 3 hours, 35 minutes, and T+plus 3 hours, 55 minutes.

Each Galileo satellite weighs about 1,580 pounds (717 kilograms) with a full load of fuel, according to a launch information kit released by Arianespace, the Ariane 5’s commercial operator.

Ground controllers at a station in Toulouse, France, will take over once the Galileo satellites are separated from the Ariane 5, establishing communications with the new spacecraft and overseeing the deployments of their solar panels.

“At the time that the four satellites separate two by two, we’ll have two shifts of the mission team working in the control room at the CNES centre in Toulouse, France, each shift managing two satellites – so it will be an intense period,” said Liviu Stefanov, Galileo co-flight director from ESA.

The ground team has normally only had to manage two satellites during this crucial “early orbit” phase, but Thursday will be different.

“This is the same team who conducted the previous Galileo early orbit phases, so we’re familiar with the satellites themselves,” says Hélène Cottet, lead flight director from CNES. “What’s different this time is managing four satellites, sometimes in sequence and sometimes in parallel. We have concentrated a lot of effort on planning and training for the first few hours in space.”

In the weeks after the launch, the satellites will be commanded to drift a few hundred miles higher to join the rest of the Galileo fleet. The rocket intentionally deploys the craft into a slightly lower orbit to avoid congesting the constellation with space junk.

“It will be a challenge, but having already taken 14 Galileo satellites into orbit, our joint teams are confident of our abilities and skills,” said Hervé Côme, Galileo co-flight director from ESA. “We know we can rely on teamwork and expertise, and we’re looking forward to a smooth lift off for Galileo’s first quad launch.”

The satellites, made by OHB System in Bremen, Germany, should enter service in early 2017. They carry L-band navigation instruments supplied by SSTL based in Guildford, England.

ESA and the European Commission have eight more satellites in the OHB/SSTL pipeline after Thursday’s launch, but the institutions plan to order another batch of spacecraft soon to give the Galileo fleet sufficient spares.

The Galileo network needs 24 satellites for global coverage.

The final countdown will begin 0058 GMT Thursday (7:58 p.m. EST Wednesday), followed by a check of the Ariane 5’s electrical systems at 0228 GMT (9:28 p.m. EST).

Workers will also put finishing touches on the launch pad, including the closure of doors, removal of safety barriers and configuring fluid lines for fueling. The flight program for Thursday’s launch will be loaded into the rocket’s computer.

The launch team will begin the process to fuel the rocket with super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants around 0806 GMT (3:06 a.m. EST). First, ground reservoirs will be pressurized, then the fuel lines will be chilled down to condition the plumbing for the flow of super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, which are stored at approximately minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit and minus 298 degrees Fahrenheit, respectively.

It will take approximately two hours to fill the Ariane 5 core stage tanks.

The storable liquid propellants on the Ariane 5’s second stage and the pre-packed powder fuel inside the Ariane 5’s twin boosters are already loaded.

Chilldown conditioning of the Vulcain 2 first stage engine will occur at 1003 GMT (5:03 a.m. EST), and a communications check between the rocket and ground telemetry, tracking and command systems is scheduled for 1156 GMT (6:56 a.m. EST).

The computer-controlled synchronized countdown sequence will begin seven minutes before launch to pressurize propellant tanks, switch to on-board power and take the rocket’s guidance system to flight mode.

The Vulcain 2 engine will ignite as the countdown clock reaches zero, followed by a health check and ignition of the Ariane 5’s solid rocket boosters seven seconds later to send the 1.5 million-pound launcher skyward.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.