One of SpaceX’s most loyal commercial customers, the European-based telecom satellite operator SES, remains committed to flying a spacecraft aboard a “refurbished” Falcon 9 booster as soon as the company resumes rocket flights, officials said.

SpaceX and SES announced the reused rocket deal Aug. 30, two days before a Falcon rocket exploded during fueling for a pre-launch test at Cape Canaveral.

A spokesperson for SES confirmed since the accident that the company will keep its agreement to launch the SES 10 communications satellite on SpaceX’s first launch of a previously-flown Falcon 9 booster.

The launch of SES 10 was scheduled for late October before the Sept. 1 launch pad mishap, but Falcon 9 missions are grounded while SpaceX investigates the cause. Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer, said Tuesday that Falcon 9 flights could resume as early as November.

“SES 10 just fit with us and also in SpaceX’s manifest,” said Martin Halliwell, chief technology officer for Luxembourg-based SES. “So we decided that this is the one that we were going to go for.”

The 156-foot-tall (47-meter) first stage slated to launch SES 10 first flew with a Dragon supply ship heading to the International Space Station. The booster made a propulsive vertical landing on SpaceX’s barge in the Atlantic Ocean a few minutes after the April 8 launch.

The second stage of the Falcon 9 will still be manufactured new for each mission, at least for the foreseeable future.

None of those plans have changed in the wake of the Sept. 1 launch pad accident, but officials are not sure when the SES 10 mission will take off. It was second in line on SpaceX’s manifest before the launch pad explosion.

In an interview with Spaceflight Now the day before the accident, Halliwell declined to disclose the value of the deal. SES originally inked the SES 10 launch contract with SpaceX in 2014, but Halliwell said it was bundled together with contracts to launch other SES satellites.

The companies signed a separate agreement to cover the specifics of the partially reusable rocket launch, and the financial terms.

“We got a discount,” Halliwell said. “I can’t go into the specific pricing, but we did get a discount for being an early adopter of the technology.”

In response to a question whether the discount was closer to potential figures publicly disclosed by SpaceX’s Shotwell and SES chief executive Karim Sabbagh — who discussed possible reusability discounts of 30 percent and 50 percent, respectively — Halliwell said: “It certainly came out closer to Gwynne than to Karim.”

The figures, while stated as unofficial and somewhat arbitrary, illustrated the behind-the-scenes negotiation on the real price of a reused Falcon 9.

Halliwell did not confirm whether the ultimate price for the SES 10 launch fell between the 30 percent and 50 percent discount figures.

“We did receive a good discount on the baseline price,” he said. “It’s not as crazy or spectacular as you might think, and that makes sense. SpaceX has to supply an awful lot of equipment, and they have to do an awful lot of refurbishment.

“It is an interesting price, and it’s something which we believe will be meaningful going forward, and will be meaningful for the industry in the longer term,” he said.

SES says there was “no material change” to the insurance coverage or the company’s premium payment after cinching the agreement to launch SES 10 on a “flight-proven” rocket.

SpaceX lists on its website the price of a newly-built Falcon 9 launch as $61 million, but industry officials say that price oscillates lower and higher depending on the requirements, and timing, of a specific mission.

SES has been en early adopter of SpaceX’s launch services since 2013, when the telecom firm placed the SES 8 television broadcast station on the first Falcon 9 launch bound for a high-altitude geostationary transfer orbit, the favored destination for most large communications satellites.

Last year, the SES 9 satellite successfully flew on just the second launch of an upgraded Falcon 9 rocket burning super-chilled densified propellants, which give the launcher the capability to heave more massive payloads into orbit.

Now SES is again hitching on to SpaceX’s effort to reshape the launch industry with lower prices, an outcome SpaceX managers say will come with “rapid and complete” reusability, which could slash costs by an order of magnitude or more in the long run.

SpaceX’s partially reusable Falcon 9 is not likely to meet that long-term objective in the next few years, but any reduction in the company’s launch prices — already the lowest in global market for the Falcon 9’s size — should add pressure to SpaceX’s competitors.

Halliwell downplayed any added risk to the SES 10 launch from the decision to launch the craft on a reused booster.

“To be frank, it’s less risky,” Halliwell said. “We know the engines work. We know that they perform correctly. We know the lifetime cycle of the engines. We know the testing. It is truly flight-proven, so quite honestly, apart from the emotion associated with it, thinking, ‘Wow, is it going to be an additional risk?’, if you actually look at it in the calm light of day, then it’s absolutely a wash.”

Halliwell said SES engineers have visited SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California, and SpaceX’s test site in Central Texas to observe manufacturing, refurbishment and tests ahead of the SES 10 launch.

He said the Falcon 9 booster assigned to the SES 10 launch has completed an engine hotfire on the test stand in McGregor, Texas. The stage required some refurbishment, but Halliwell did not go into details.

None of the nine Merlin engines from the April 8 launch were replaced on the stage ahead of the SES 10 launch, he said.

The Merlin 1D engines were already qualified for multiple flights, but SpaceX’s testing this year has focused on the resiliency of the overall booster stage, comprising tanks and welded structures, to withstand two or more flights.

A separate Falcon 9 first stage recovered after a subsequent launch in May has been test-fired in McGregor seven times since late July.

One of the parts of the rocket SpaceX engineers were most concerned about earlier in the reuse initiative was the bottom of the booster, where the nine Merlin engines are mounted with their intricate plumbing. That part of the rocket points forward during the Falcon 9’s descent, subjecting it to high re-entry temperatures and the effects of the engine plume during braking burns guiding the first stage to its landing target.

But SES says the rocket for SES 10 looks good.

“It is in extraordinarily good condition,” Halliwell said. “I thought there would be significant damage at the aft end. Absolutely not. It was in really good shape.”

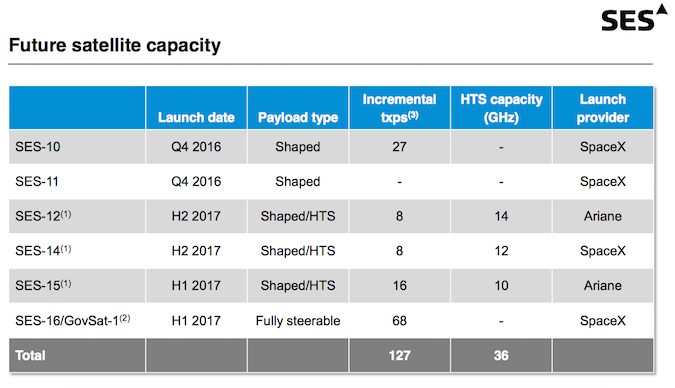

Four of seven satellites SES has under construction are contracted to launch aboard SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets. Another two will blast off on Ariane 5 launchers, while a telecom craft ordered from manufacturer Thales Alenia Space earlier this month has not been assigned for launch services.

Before the Sept. 1 pad explosion, the SES 10 and SES 11 satellites were supposed to launch on Falcon 9 rockets before the end of the year. Both spacecraft are finished with ground testing at Airbus Defense and Space’s satellite factory in Toulouse, France, and awaiting shipment to Cape Canaveral.

Halliwell said the SES 11 satellite will fly on an all-new Falcon 9 booster.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.