Rising into a midnight sky lit by the full moon, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket took off from Cape Canaveral early Monday with a commercial cargo craft on the way to the International Space Station, then returned to Florida’s Space Coast for a dramatic nighttime landing.

The Falcon 9 rocket released the Dragon cargo capsule in orbit less than 10 minutes after liftoff, sending the gumdrop-shaped supply ship on a two-day trip to the space station, the second resupply mission to head for the orbiting research complex in two days.

The launch of the Dragon capsule, a spaceship with pressurized and external compartments, was the prime objective of Monday’s launch, but SpaceX also nailed another experimental landing of the Falcon 9’s first stage, the second time the company has achieved such a feat on land at Cape Canaveral.

The 213-foot-tall (65-meter) Falcon 9 rocket ignited its nine Merlin 1D first stage engines and climbed away from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad at 12:45:29 a.m. EDT (0445:29 GMT) Monday, riding a bright exhaust plume through high-level clouds streaking northeast from the Atlantic coastline.

The Falcon 9’s first stage booster disconnected at an altitude of 40 miles — about 65 kilometers — and fired cold-gas nitrogen thrusters to flip around, flying tail first as it ignited three of its nine Merlin engines for a “boost-back” burn to begin steering back toward Cape Canaveral.

Putting on a spectacle high above Florida’s Space Coast, the Falcon 9’s two rocket stages appeared as bright dots surrounded by a ball of flickering rocket exhaust. The second stage continued northeast with the Dragon supply ship, accelerating it to a velocity of more than 5 miles per second (8 kilometers per second) to reach low Earth orbit.

Meanwhile, the 15-story first stage re-ignited three of its engines again about six-and-a-half minutes into the mission for an entry maneuver, then fired up its center engine to brake for a vertical propulsive touchdown about eight minutes after liftoff.

A thundering sonic boom crackled across the Florida spaceport as the rocket touched down, heralding the booster’s homecoming. The hard-to-miss, window-rattling sound is a reminder for many Space Coast residents of the supersonic approach of the space shuttle, which sent a double sonic boom across the landing site a few minutes before gliding down to the runway.

“It had a characteristic double boom, and people knew, ‘Oh, yeah, the shuttle is coming back,'” said Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of flight reliability, who heard some of the shuttle sonic booms as the space planes flew over Los Angeles on approach to Edwards Air Force Base, California.

“I think it’s going to be the same thing eventually when people get used to this particular sonic boom, being slightly different (than the shuttle’s),” Koenigsmann said. “They will say, ‘Stage 1 is coming back. Falcon 9 is coming back and landing.'”

The breathtaking rocket-assisted descent has been tried only once before Monday at Cape Canaveral. A Falcon 9 first stage came down to a smooth touchdown Dec. 21 after launching with 11 Orbcomm communications satellites.

Monday’s launch landing appeared to go just as SpaceX planned.

“We had a really great launch on Falcon 9, and a perfect orbit insertion on Dragon,” Koenigsmann said. “And Stage 1 came back to land.”

The landing is another achievement for SpaceX’s plan to reuse rocket stages. The company wants to launch a mission aboard a previously-flown Falcon 9 first stage later this year, with extensive hardware testing and negotiations with prospective customers currently underway.

But the launch’s main purpose was the delivery of a fresh batch of supplies, provisions and experiments to the International Space Station, part of a nearly $3 billion contract between NASA and SpaceX that helped seed development and provided a key customer base for the Falcon 9 and Dragon vehicles.

Loaded with 4,975 pounds (2,257 kilograms) of cargo, the Dragon capsule is on a two-day pursuit of the space station, with arrival expected Wednesday.

“The Dragon is doing fine,” said Joel Montalbano, NASA’s deputy program manager for space station utilization. “We’re looking for a grapple Wednesday morning, in Eastern time, at about 7 a.m. (1100 GMT).”

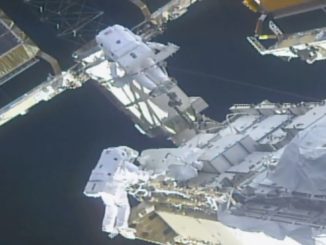

Astronaut Jeff Williams will use the station’s robotic arm to grab the free-floating Dragon spaceship, then ground controllers will command the arm to place the cargo craft on the Earth-facing side of the Harmony module.

Items stowed aboard the Dragon capsule include a new docking adapter to welcome commercial piloted spaceships being developed by Boeing and SpaceX.

The International Docking Adapter-2, or IDA-2, is bolted inside the Dragon’s unpressurized cargo carrier, or trunk. The space station’s robotic arm will pluck the docking adapter from the Dragon’s trunk Aug. 16, and Williams and crewmate Kate Rubins will go outside on a spacewalk Aug. 18 to help install the new docking port on the front end of the Harmony module, where Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon crew capsules will park with arriving astronauts.

A similar docking adapter was lost in June 2015 when a Falcon 9 rocket disintegrated over the Atlantic Ocean two minutes after launch, destroying a Dragon cargo freighter and its contents.

NASA signed a $9 million contract with Boeing to build a third docking port to replace the unit lost last year. The space agency wants two docking adapters on the space station to support the presence of two U.S. crew vehicles at the same time.

IDA-2 weighed about 1,029 pounds (467 kilograms) at launch, measuring about 42 inches (1.1 meters) tall and 63 inches (1.6 meters) wide.

“The docking adapter is another step forward to enabling the commercial crew vehicles,” Montalbano said.

The docking port is one of the biggest external components to be added to the space station since large-scale assembly of the outpost ended with the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011.

Spacewalkers will install the docking adapters over the station’s existing U.S. arrival ports designed for space shuttle dockings. The new docking ports use a different design to receive any spacecraft, including the SpaceX Crew Dragon and Boeing CST-100 Starliner spacecraft, future cargo freighters, and other craft yet to be developed.

The space station crew will unpack 3,946 pounds (1,790 kilograms) of equipment from the Dragon’s internal cargo cabin after the ship’s rendezvous Wednesday. The supply manifest incldues 2,050 pounds (930 kilograms) of scientific experiment hardware and 815 pounds (370 kilograms) of clothing, food and other provisions for the crew.

Other items include a spacesuit, tools and spare parts, computers, and logistics for the space station’s Russian segment.

The SpaceX resupply run launched a day after a Russian Progress cargo and refueling freighter departed the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. It is due to link up with the space station Monday night, U.S. time.

Monday’s middle-of-the-night blastoff was the ninth operational space station resupply mission dispatched by SpaceX. The Hawthorne, California-based firm has contracts for at least 17 more confirmed logistics missions through 2024, plus options for more.

NASA has a similar resupply arrangement with Orbital ATK, and Sierra Nevada Corp.’s Dream Chaser space plane should begin cargo delivers to the space station in 2019.

The successful launch Monday was the seventh Falcon 9 flight of the year, and SpaceX has two more commercial launches on its schedule in August. First comes the launch of the Japanese JCSAT 16 communications satellite in the second week of August, followed around the end of the month with the launch of the Israeli Amos 6 telecom payload, Koenigsmann said.

Both missions will put the satellites into egg-shaped geostationary transfer orbits, the destination favored by large telecommunications satellites. Such trajectories require greater speed and travel too fast for the rocket to turn around and return to the launch base, so for those missions SpaceX will target booster landings on a barge positioned several hundred miles offshore.

With Monday’s flight in the books, SpaceX is now 5-for-10 in booster recovery attempts since the vertical landing scheme debuted with experimental descents to the landing barge in January 2015. Breaking down the numbers between landings onshore and offshore, the Falcon 9 is 2-for-2 with descents over land and 3-for-8 at sea.

Engineers say the trajectory to return the first stage booster to land puts less stress on the rocket than high-speed dives back through the atmosphere on the way to the ocean platform, or drone ship, but only a fraction of the Falcon 9 missions have enough fuel reserve to steer back toward Cape Canaveral.

“It’s a pretty good-sized landing pad compared to the drone ship, and it doesn’t have structure (to the) left and right that you need to fit the vehicle in,” Koenigsmann said. “From that perspective, it’s going to be easier (to return to land). Getting back to land requires significantly more propellant, but at the end of the day, those trajectories are also easier and more benign in terms of heat load and deceleration.”

Koenigsmann said the next Falcon 9 landing onshore will likely occur after SpaceX’s next space station logistics launch, a flight set for liftoff on November.

The stage that landed after Monday’s flight appeared to weather the mission well.

SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk tweeted a picture from Landing Zone 1, the Falcon 9’s landing base, shortly after the flight.

Out on LZ-1. We just completed the post-landing inspection and all systems look good. Ready to fly again. pic.twitter.com/1OfA8h7Vrf

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) July 18, 2016

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.