When Chris Ferguson climbed into the commander’s seat of the shuttle Atlantis five years ago Friday for the spaceship’s final flight, he didn’t know what turn his career would take when he returned to Earth.

Like many space shuttle workers, Ferguson had to decide what to do next. Atlantis’ final flight, which lifted off July 8, 2011, was Ferguson’s third space mission and capped a nearly 30-year flying career with the Navy and NASA.

He reminisced about Atlantis’ 13-day mission in 2011 last month during an informal meeting with reporters.

“On the last day, I tried to make it a point to say goodbye to every shift (in mission control) because I knew when they left the control center it was never going to be the same for them, so we tried to make it special for them,” Ferguson said. “After the last goodbye, I thought, you know what? I have no idea where I’m going to be in a month. I knew we had all the post-flight stuff to do, but I had no idea what my future held. Am I going to go teach at college? What am I going to do?”

The shuttle’s retirement drastically cut flight opportunities for NASA’s astronaut corps, who now ride to the space station one at a time on Russian Soyuz capsules.

After joining Boeing in late 2011, Ferguson helps lead the company’s development of the CST-100 Starliner space taxi, one of two U.S.-built commercial spacecraft selected by NASA to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station.

“Now I find myself right back in the fight again, right back in the fight as a stakeholder in making sure that we’re successful,” Ferguson said.

Five years after the space shuttle’s swan song, two vehicles are racing to be the first to restore U.S. human spaceflight capability.

Boeing CST-100 Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsules are the contenders, with Boeing aiming for a first orbital demonstration flight with two test pilots in February 2018. SpaceX says the Crew Dragon is set for its first crewed test flight, also with two astronauts, in late 2017.

NASA’s contract with Boeing has a maximum value $4.2 billion. SpaceX’s commercial crew deal with the space agency is worth up to $2.6 billion.

Both companies say their schedules are success-oriented, and officials from Boeing, SpaceX and NASA acknowledge the timelines are tight to meet those dates. Safety is also paramount, managers said, and supersedes any schedule commitment.

Atlantis’ last crew left a small U.S. flag aboard the space station to be returned by the next American crew transport that reaches the complex.

Ferguson is often asked whether he will fly on the first CST-100 Starliner test mission. Boeing plans to send a company test pilot and a NASA astronaut on the demo flight to the space station in early 2018, but managers have not selected the crew members.

NASA has assigned four astronauts — Robert Behnken, Eric Boe, Douglas Hurley and Sunita Williams — to train for the initial CST-100 and Crew Dragon flights. A decision on crew for the first demo mission is not expected until next year.

Boeing’s CST-100 program is headquartered at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, a few miles from the Atlas 5 rocket’s launch pad where they will blast off to the space station. Ferguson now has an office at KSC, where he oversees crew and mission operations.

“I was standing at my office desk looking out the window, and I saw the last Falcon 9 launch,” Ferguson said. “There are worse office desks in the world. We see the SLS (Space Launch System) platforms going together. There’s a lot of activity at KSC.”

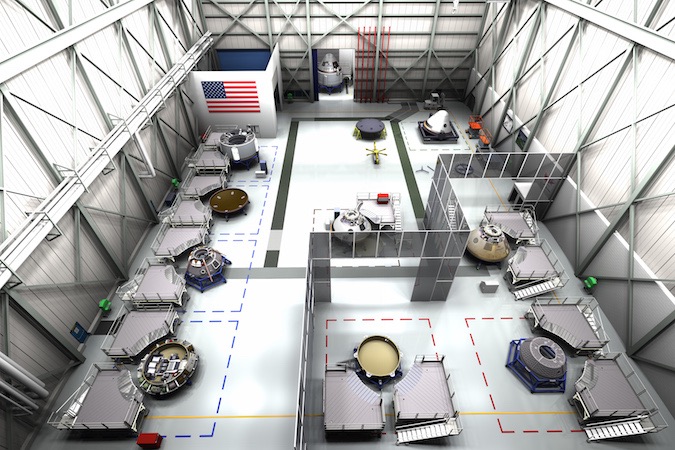

Boeing leased a former shuttle hangar at the spaceport to assemble CST-100 Starliners, and the company transferred management of the commercial crew program to Florida to be near the capsule’s launch facility.

The U.S. Air Force’s reusable uncrewed X-37B space plane, also built and refurbished by Boeing, is housed at a modified shuttle processing building a few hundred feet from the CST-100 capsule assembly line. Inside the nearby Vehicle Assembly Building, workers are building up platforms inside High Bay 3 for the Space Launch System, a super-heavy-lift rocket NASA plans to use for human expeditions into deep space, starting with piloted flights around the moon in the early 2020s.

Launch pads at Cape Canaveral are also seeing changes.

The historic launch complex used for the Apollo 11 moon landing mission — and last used on the final shuttle flight in 2011 — is now under SpaceX management. The California-based company, led by Elon Musk, will base all of its Crew Dragon launches on Falcon 9 rockets from launch pad 39A, which workers are now outfitting with infrastructure to support astronaut flights.

Construction cranes built up a crew access tower last year at Complex 41, United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 launch pad, to allow astronauts to board Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner. A crew access arm and white room will be added in the coming weeks, Ferguson said.

“It’s a far cry from where it was four-and-a-half years ago at this time,” Ferguson said. “There are a lot of cars in the parking lot, a lot of different activities, three different spacecraft that will carry humans in various stages of development, whether it’s the pad, the VAB platforms for SLS, our spacecraft, and X-37 is right across the aisle.

“It’s sort of a hopping place. For each one, it’s like are we all going to live in this symbiotic relationship where we’re all providing reliable inexpensive transportation to low Earth orbit,” Ferguson said. “That, to me, is sort of like nirvana.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.