The European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission will end Sept. 30 with a dicey descent to the core of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, a risky, but potentially rewarding finale punctuated by commands to automatically safe the probe’s rocket thrusters and turn off its radio transmitter.

The landing at the end of September will conclude nearly 26 months of research since Rosetta arrived at the previously-unexplored world, wrapping up the most extensive survey ever made at a comet.

Since Rosetta arrived at comet 67P in August 2014, the spacecraft has watched the dark, craggy world erupt in activity — plumes, jets and massive discharges of gas and dust — as it cruised into the inner solar system, reaching a point 115 million miles (186 million kilometers) from the sun on Aug. 13, 2015, where sunlight and temperatures reached their peak.

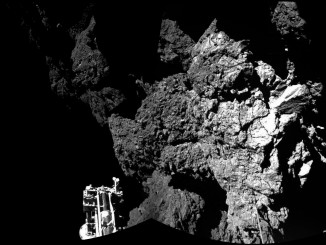

Rosetta dropped the Philae spacecraft to the comet’s surface in November 2014, dispatching the piggyback probe to the first landing on a comet in history.

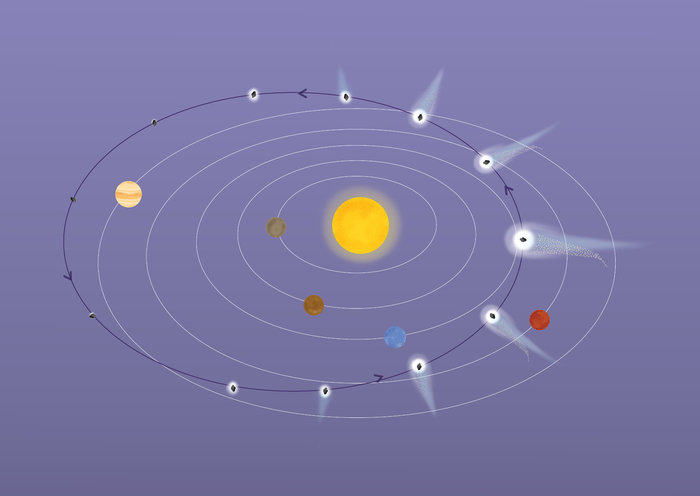

Comet 67P is now on the outbound leg of its nearly 6.6-year orbit, heading for the cold, dim reaches of the outer solar system beyond the orbit of Jupiter.

At such distances, Rosetta’s solar panels will be unable generate enough electricity to keep the spacecraft operating, and the robot is unlikely to survive a second stint in hibernation, ESA officials said. Ground controllers put Rosetta to sleep for part of its 10-year journey to comet 67P, but the craft never ventured as far from the sun as it will in the coming years.

“We’re trying to squeeze as many observations in as possible before we run out of solar power,” said Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist. “30 September will mark the end of spacecraft operations, but the beginning of the phase where the full focus of the teams will be on science. That is what the Rosetta mission was launched for and we have years of work ahead of us, thoroughly analysing its data.”

Rosetta launched more than 12 years ago, on March 2, 2004, and is currently in an extended mission phase. The aging probe completed all its primary objectives last year.

Managers decided more than a year ago to end Rosetta’s mission with a landing attempt, and meetings in recent weeks have nailed down some details of the descent and set Sept. 30 as the official target date.

Rosetta’s maneuvering thrusters will begin changing the spacecraft’s path around comet 67P in August to set up for the landing, placing the probe in a series of elliptical orbits that take it ever-closer to the comet’s nucleus, officials said.

“Planning this phase is in fact far more complex than it was for Philae’s landing,” said Sylvain Lodiot, ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft operations manager. “The last six weeks will be particularly challenging as we fly eccentric orbits around the comet – in many ways this will be even riskier than the final descent itself.”

Perils awaiting Rosetta include the comet’s lumpy gravity field, which could drive the spacecraft off course, and dust grains streaming away from the nucleus that could disrupt the orbiter’s navigation cameras, confusing the particles for stars used as pointing references.

“The closer we get to the comet, the more influence its non-uniform gravity will have, requiring us to have more control on the trajectory, and therefore more maneuvers – our planning cycles will have to be executed on much shorter timescales,” Lodiot said in a statement.

A navigation error triggered by dust put the spacecraft into safe mode last month just 3 miles, or 5 kilometers, from the comet.

“Although we’ll do the best job possible to keep Rosetta safe until then, we know from our experience of nearly two years at the comet that things may not go quite as we plan and, as always, we have to be prepared for the unexpected,” said Patrick Martin, ESA’s Rosetta mission manager.

The uneven gravity field around comet 67P keeps Rosetta from attaining a stable circular orbit, with the nucleus tugging on the spacecraft more or less depending on the probe’s exact location relative to the comet. That will keep navigators on edge at at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany.

“This is the ultimate challenge for our teams and for our spacecraft, and it will be a very fitting way to end the incredible and successful Rosetta mission,” Marin said.

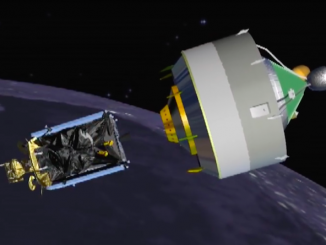

A final rocket firing about 12 hours before landing will set Rosetta on a course for a controlled impact with the comet. Scientists and engineers in charge of the mission have not selected a specific touchdown zone yet, but they expect Rosetta to return close-ups with inch-scale resolution.

Rosetta will hit the comet’s surface at about 1.1 mph, or 50 centimeters per second, roughly half of the landing speed of Philae.

But Philae carried a landing gear, and Rosetta was never designed to survive such a maneuver. With solar panels stretching 105 feet (32 meters) tip-to-tip, longer than a basketball court, the mothership carries a dish-shaped antenna, scientific instruments and a propulsion system optimized for flight in deep space.

The safing procedures will kick in at the moment of touchdown, ESA officials said, to keep Rosetta from unexpectedly moving and contaminating the comet with rocket exhaust. Rosetta’s transmitter will go silent to avoid interfering with radio communications with other deep space missions.

The only way to reliably turn off the transmitter is to pre-program Rosetta to switch off on impact, rather than counting on the spacecraft to survive the landing, officials said.

Scientists would be unable to communicate with Rosetta for long anyway, even if its antenna somehow remained pointed at Earth. The comet rotates every 12 hours, and Rosetta will quickly disappear from view.

Data returned from the Philae lander beamed back to Earth via a relay from the Rosetta orbiter, an asset no longer available after the Sept. 30 descent.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.