EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated to correct spelling of Hal Levison’s name.

Launches of interplanetary missions can only depart Earth when the positions of the planets are just right, and officials managing the development of probes set for launch in 2021 and 2022 to explore asteroids and Jupiter says construction milestones and reviews are proceeding to keep the projects on schedule despite the coronavirus pandemic.

NASA’s next planetary mission, the Perseverance Mars rover, remains on schedule for liftoff July 17 from Cape Canaveral. NASA has assigned a high priority to the Perseverance rover, and agency is using government aircraft to shuttle workers between the Kennedy Space Center and the rover team’s home base at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

The Perseverance rover mission, estimated to cost roughly $2.7 billion, is the first Mars rover NASA has launched to the Red Planet since 2011. The mission has a 20-day window to depart Earth in July or August, or else wait for the next alignment of Earth and Mars in 2022, a delay that NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said could cost $500 million.

Although they haven’t received the same top-priority classification as the Perseverance Mars rover, other planetary missions with launch windows in the next couple of years are progressing toward their launch dates.

The Lucy mission, a robotic probe to study an unexplored population of asteroids, is on track for liftoff in October 2021.

Lockheed Martin is set to begin assembling the spacecraft in August, and production of major components is well underway, according to Hal Levison, the Lucy mission’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute.

Like other major aerospace contractors, Lockheed Martin’s spacecraft manufacturing facility near Denver is exempt from local and state stay-at-home orders.

“Aerospace is considered an essential industry,” Levison said. “Except at Goddard Space Flight Center, which is closed, all the work is getting done that needs to get done. People have gone to weird schedules. They’ll have two schedules in a day, and they’ll have half as many people there, and they’re working in teams to handle and minimize the threat from the virus. But all the work is continuing to happen.”

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center is in charge of developing one of Lucy’s science instruments, a color imager, but the space center is closed to all personnel, except employees required to protect life and critical infrastructure.

While hands-on work continues on most of the Lucy spacecraft’s components, all members of the science team are working remotely.

“Originally, the infrastructure of the telecommuting couldn’t handle the transition, so there was a lot of frustration,” Levison said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “There are psychological impacts. (That’s) probably the worst aspect of it. You build very close relationships with your team members, and a lot of that comes from being in the same room with them. So not having that is a drag.”

Levison said Lucy’s engineering team has largely cleared technical issues related to the Lucy spacecraft’s fan-shaped UltraFlex solar arrays and propulsion system.

“Right now, we’re in the process of building what we need to put it all together,” Levison said. “We’ve had our share of challenges. The solar arrays, which are huge, didn’t scale up from the previous designs as well as we had hoped. So that has been a challenge for them. We’ve had some things happen with propulsion that were sort of self-inflicted.”

But those issues are largely behind the Lucy team, Levison said. The schedule has a couple of months of margin to meet Lucy’s planned launch date of Oct. 16, 2021, on top of a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

“So far, all the technical issues we’ve had are now solved,” he said. “So really, except for the virus, there’s nothing between us and getting to the finish line on time. Our budget situation is actually really healthy … So far, everything looks good.”

Lucy’s UltraFlex solar arrays, made by Northrop Grumman, are bigger versions of the fan-shaped solar arrays flown on the Cygnus space stations supply ship.

“Scaling things up, it’s much more complicated than the previous ones were,” Levison said. “So that was a challenge that they needed to take a step back and redesign, for example, the central hub. These solar arrays open like a Chinese fan, so getting all the wiring through the hub was a problem.”

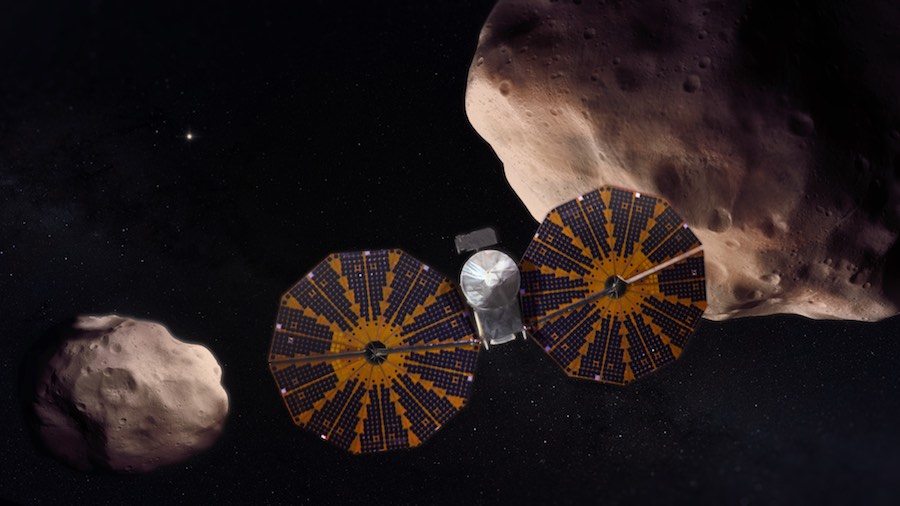

The nearly $1 billion Lucy mission will be the first to visit a class of solar system objects known as the Trojan asteroids, which orbit in tandem with Jupiter, with groups ahead of and behind the giant planet in its path around the sun. Scientists believe the Trojan asteroids represent a diverse sample of the types of small planetary building blocks that populated the solar system after its formation 4.5 billion years ago.

Lucy will fly by seven different asteroids from 2025 through 2033.

If the mission misses its October 2021 launch window, there’s a backup launch opportunity in October 2022, Levison said.

Preparations for launch of the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or JUICE, mission have also continued as scientists and managers work remotely.

Technicians working on the JUICE spacecraft itself have largely kept pace with pre-coronavirus schedules, but some development delays related to the pandemic are likely inevitable, according to Giuseppe Sarri, ESA’s JUICE project manager.

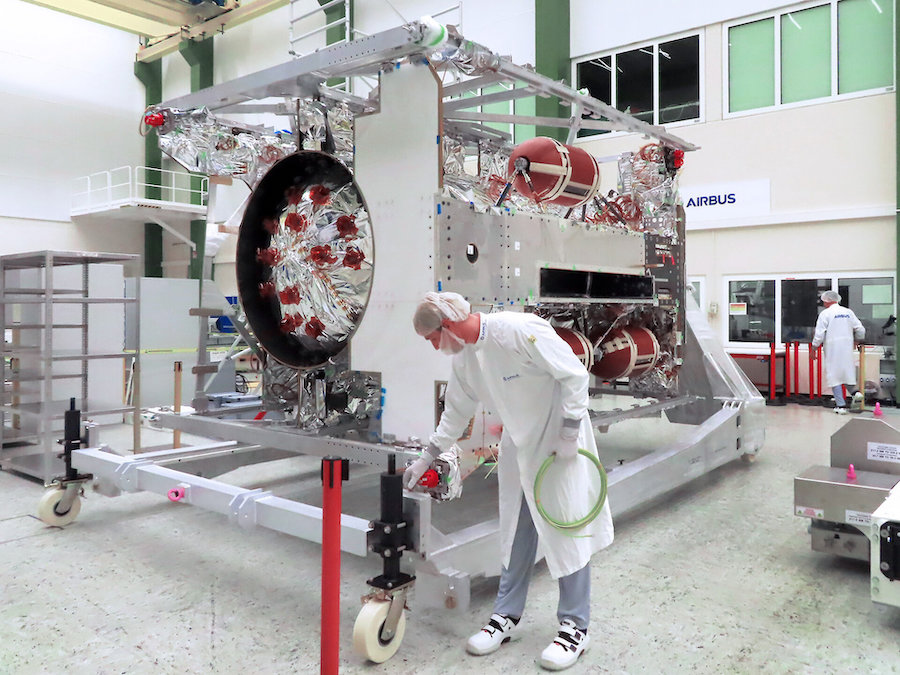

In early April, the JUICE spacecraft chassis departed ArianeGroup’s Orbital Propulsion Center in Lampoldshausen, Germany, where technicians integrated the probe’s chemical propulsion system. Teams then delivered the JUICE spacecraft to an Airbus Defense and Space facility in Friedrichshafen, Germany, where JUICE’s prime contractor will begin installing electronic units.

“Most of the industrial team is working in shifts,” Sarri said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “The way they work is they have two shifts of six hours each, not overlapping.”

The two shifts help ensure technicians can meet physical distancing guidelines, with a limited number of people inside the manufacturing facility at one time.

“Therefore, this allows them to work,” Sarri said. “I’m not saying it’s (entirely) nominal because there’s some inefficiency in the transfer, but the activities that were on the critical path, they are still nominal.”

JUICE’s primary launch window opens May 21, 2022, and extends until June 10 of that year. It will launch on an Ariane 5 ECA or Ariane 64 rocket from Kourou, French Guiana.

Assuming a launch in May or June 2022, JUICE will reach Jupiter in October 2029 and conduct a series of close flybys of three of Jupiter’s icy moons — Callisto, Europa and Ganymede — before entering orbit around Ganymede itself in December 2032. With the final phase of JUICE’s mission at Ganymede, the spacecraft will become the first in history to orbit around the moon of another planet.

JUICE is the first European-led mission to the outer solar system.

The mission’s 10 remote sensing, geophysical and in situ instruments include a camera suite, spectrometers, a laser altimeter for topographic measurements, an ice-penetrating radar, and a package of plasma wave sensors, particle detectors, a magnetometer, and a payload to study the gravity field of Jupiter and its moons.

Scientists want to learn more about Jupiter’s atmosphere and magnetosphere, and collect up-close data about Jupiter’s three moons believed to harbor underground oceans of liquid water.

In parallel with the spacecraft assembly work in Germany, teams around Europe and in the United States are building and testing JUICE’s scientific instruments.

“There is a scientific institution which is in charge of each instrument, but most of the work is done by industry,” Sarri said. “That is the case for the Italian instrument, and the same for the two German instruments. So for those instruments, the industry is working in shifts. That’s allowed to continue.

“It’s more difficult for instruments where there is an institution like a university or a research center because they have less capability to organize in shifts, to work extended hours, etc. But I would say that they are almost all still working.”

Sarri said JUICE had around three months of schedule margin before the coronavirus pandemic hit.

“I would expect we will have to erode part of of our margin,” Sarri said. “I’m not positive, but I think that we will not eat up all the margin … Of course, we will have less margin, which means that if we have other problems in the future we will be a bit less healthy in terms of margin.”

The next launch opportunity for JUICE is just three months later — in August and September 2022. But the backup launch window would put JUICE on a slower trajectory toward Jupiter. The three-month slip would result in a two-year delay in JUICE’s arrival at the giant planet from 2029 to 2031.

“I’m very positive to launch in 2022, and I’m still reasonably optimistic to keep it in June 2022,” Sarri said. “It’s clear that we are accumulating a delay, but it’s not dramatic yet. It depends on how far the situation will go.”

Development of NASA’s Psyche mission — scheduled for launch in July 2022 on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket — is also continuing, according to Lindy Elkins-Tanton, the mission’s principal investigator from Arizona State University.

Maxar, formerly known as Space Systems/Loral, is building the Psyche spacecraft in Palo Alto, California.

Production of the chassis of the Psyche probe has started at Maxar, which completed the spacecraft’s critical design review April 15. A mission-level critical design review is scheduled for next month to finalize and freeze the overall design.

Assuming a launch in July 2022, the Psyche spacecraft will reach Mars in May 2023, where it will use the planet’s gravity to slingshot into the asteroid belt. The spacecraft is scheduled to arrive at asteroid Psyche in January 2026, then orbit the metallic world for 21 months.

The asteroid is about the size of Massachusetts and has an irregular shape. It completes one rotation every 4.2 hours.

Observations of Psyche through telescopes suggest the asteroid is composed largely of nickel-iron metal, suggesting the asteroid could be the leftover core from the building block of a planet, or planetesimal, in the early solar system more than 4 billion years ago.

“We’re moving forward on all fronts, though some a little more slowly than before,” Elkins-Tanton told Spaceflight Now. “Truly, safety of the team comes first.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.