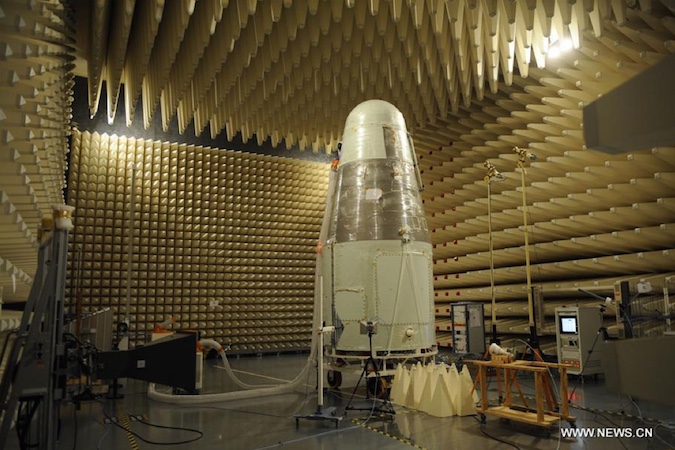

The unpiloted Shijian 10 spacecraft launched from a spaceport in northwestern China on Tuesday with a suite of microgravity research experiments developed by Chinese and European scientists.

The bullet-shaped space capsule soared into orbit aboard a Long March 2D rocket at 1738 GMT (1:38 p.m. EDT) Tuesday from the Jiuquan satellite launch center, a military-owned facility in the remote frontier of northwestern China.

The mission, also called SJ-10, carries 19 experiments investigating fluid physics, combustion in space, materials science, biotechnology, and the effects of microgravity and radiation on plants and animals, according to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which manages the program.

Shijian 10’s return capsule will descend to parachute-assisted landing in China’s Inner Mongolia region in about two weeks, while an orbital module will remain in space to conduct further experiments, the state-run Xinhua news agency reported.

The experiment package includes investigations probing how solid materials and wiring insulation ignite and burn in microgravity, how space radiation damages DNA, and the effects of the space environment on the development of mouse and silkworm embryos, according to a mission overview provided by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The investigations could aid designers of future spacecraft and help scientists study how humans could reproduce in space, researchers said.

One combustion experiment will set fire to eight fuel samples inside the Shijian 10 payload compartment and examine how they burn under different thermal and oxygen conditions.

“Current methods of screening spacecraft materials are based on how the materials burn on Earth,” scientists wrote in a paper describing the Shijian 10 mission. “The prediction of fire behavior in microgravity still involves uncertainty.”

Xinhua reported Shijian 10 also includes payloads studying how fruit flies and rat cells respond to spaceflight.

“All experiments conducted on SJ-10 are completely new ones that have never been done before either at home or abroad,” said Hu Wenrui, chief scientist of the SJ-10 mission, in a report published by Xinhua. “They could lead to key breakthroughs in our academic research.”

The 19 experiments aboard Shijian 10 were selected from more than 200 applicants, Chinese officials said.

One of the investigations was jointly developed by scientists in China and Europe.

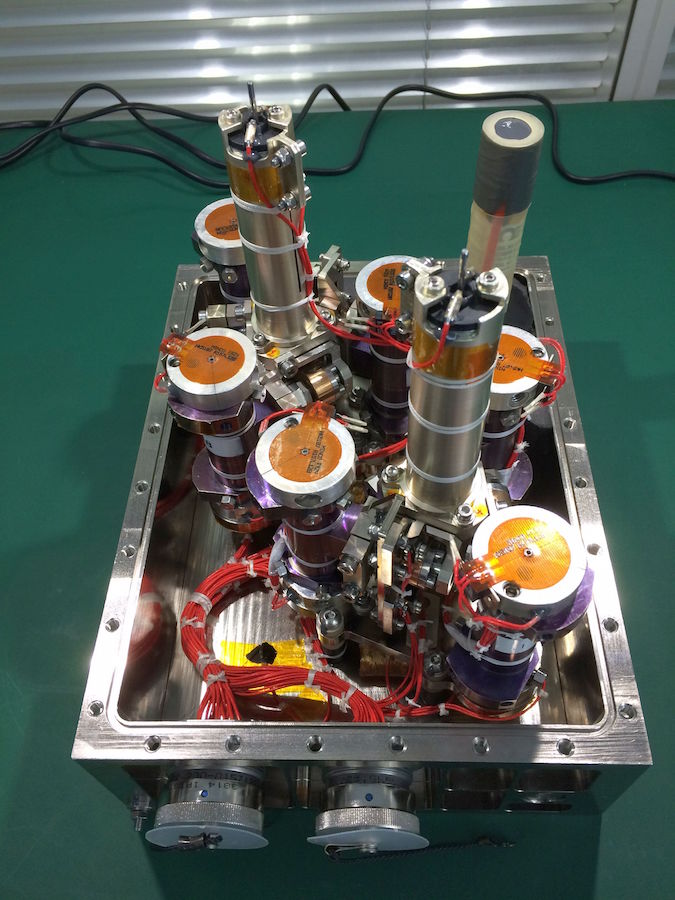

The Soret Coefficient in Crude Oil experiment will help scientists learn how oil is stored in natural reservoirs in Earth’s crust. It is a partnership between the European Space Agency, China’s National Space Science Center, France’s Total oil company and China’s PetroChina oil company.

“The experiment is designed to sharpen our understanding of deep crude oil reservoirs up to 8 kilometers (5 miles) underground,” said Antonio Verga, who oversees the project for ESA.

Six samples of crude oil, each with a volume of just one milliliter, are stowed inside sturdy titanium cylinders on the Shijian 10 satellite. They are compressed to 500 times the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere at sea level, mimicking conditions where crude oil pools deep underground.

The goal of the experiment is to study how temperature affects how crude oil molecules move.

“Imagine a packet of cornflakes – over time the smaller flakes drop to the bottom under gravity. On a molecular scale this experiment is doing something similar but then looking at how temperature causes fluids to rearrange in weightlessness,” says ESA’s Olivier Minster. “Deep underground, crushing pressure and rising temperature as one goes down is thought to lead to a diffusion effect – petroleum compounds moving due to temperature, basically defying gravity.

“Over geological timescales, heavier deposits end up rising, while lighter ones sink,” he said. “The aim is to quantify this effect in weightlessness, to make it easier to create computer models of oil reservoirs that will help guide future decisions on their exploitation.”

ESA says the crude oil payload is the agency’s first experiment on a Chinese space mission — the product of a 2006 agreement between European and Chinese space leaders.

Shijian 10 is China’s 25th recoverable satellite launched since 1974, including one spacecraft lost in a launch failure.

The launch of Shijian 10 is the second of four Chinese research satellites scheduled to blast off in a one-year period.

The Dark Matter Particle Explorer, or DAMPE, mission lifted off in December 2015 in search of the invisible matter scientists believe makes up most of the universe. A powerful X-ray space telescope to study black holes and a spacecraft designed for quantum science experiments are due for launch before the end of 2016, Xinhua reported.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.