SpaceX says Sunday is the target launch date for the first launch of a remodeled version of its Falcon 9 rocket, and the launcher’s first mission since a June failure, after completing a practice countdown and engine ignition test Friday.

The mission’s firsts, including a possible landing attempt for the Falcon 9’s first stage, make it a critical launch for SpaceX as the company simultaneously resumes flying its fully-booked manifest, debuts a new generation Falcon booster, and continues a lengthy research and development initiative into rocket reusability.

Sunday’s launch attempt is timed for 8:29 p.m. EST (0129 GMT Monday) from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad.

Sources said only an instantaneous launch opportunity is available Sunday due to restrictions imposed by the Federal Aviation Administration, which may be hesitant to re-route holiday week air traffic around the Cape Canaveral launch base for several hours in case of launch delays.

SpaceX and FAA officials did not comment on the launch window constraints for Sunday, but the federal regulatory agency has refused to approve commercial launch attempts on busy travel days before, including a 2013 SpaceX flight that tried to blast off on several days around Thanksgiving.

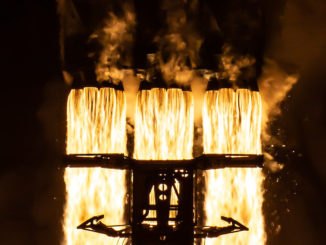

Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, announced late Friday the completion of a static fire engine test with the Falcon 9 rocket on its Florida launch pad. The static fire was set for Wednesday, but launch crews ran into problems that delayed the critical preflight milestone to Friday just before 7 p.m. EDT (0000 GMT Saturday).

In a post to his Twitter account, Musk said the launch is on track for Sunday, one day later than previously disclosed.

Saturday’s launch window extended three hours, but Sunday’s is shortened to one instant.

The launch is pending a final data review of the results of Friday’s static fire, Musk said.

Eleven satellites owned by Orbcomm, a New Jersey-based communications company, are fastened on top of the 229-foot-tall Falcon 9 rocket. They will join five identical spacecraft launched on a Falcon 9 mission in July 2014 to complete deployment of Orbcomm’s second-generation, or OG2, satellite network designed to relay messages and help owners track shipments around the world.

Orbcomm says one of six satellites sent up in 2014 has since failed in orbit.

The mission will steer the 11 Orbcomm satellites, each about 380 pounds, into an orbit approximately 400 miles above Earth. Once the 11 satellites separate from an adapter ring atop the Falcon 9’s second stage, the upper stage Merlin engine is programmed to restart for a demonstration maneuver for future missions requiring multiple burns.

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket has been grounded since a mishap shortly after a June 28 launch destroyed a commercial Dragon supply ship with cargo heading for the International Space Station.

The launch failure, coupled with efforts to qualify an upgraded Falcon 9 configuration for flight, stalled Falcon 9 missions for nearly six months.

Sunday’s return-to-flight launch will carry several upgrades to the Falcon 9 rocket, including Merlin 1D engines rated for higher thrust levels.

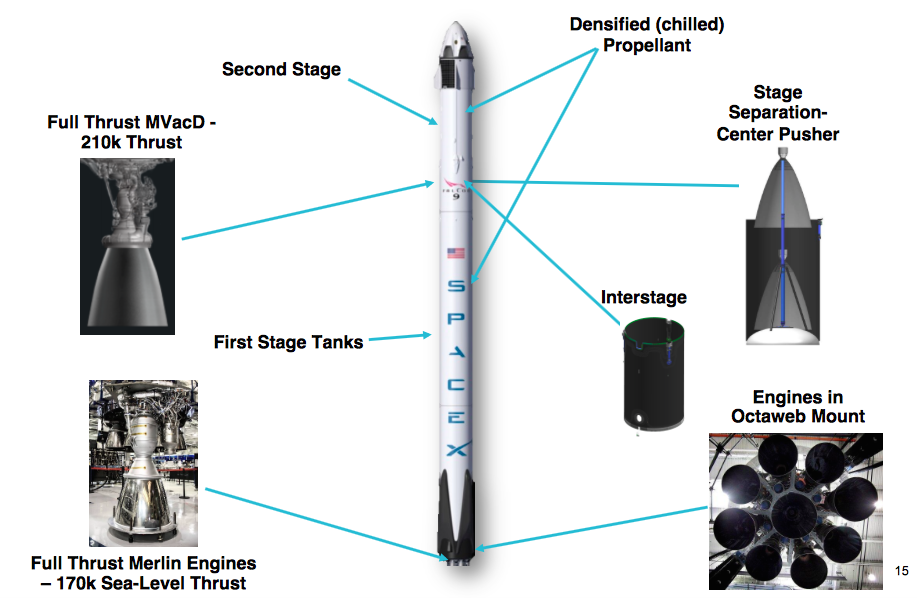

Each of the Falcon 9’s nine Merlin 1D engines, affixed to the base of the booster in an “octaweb” arrangement, will generate 170,000 pounds of thrust at sea level. The engines will collectively produce more than 1.5 million pounds of thrust.

The older generation Falcon 9 rocket had first stage engines that ramped up to a maximum power level of 147,000 pounds of thrust, or 1.3 million force-pounds when firing together.

A space-rated Merlin engine on the upper stage will have a maximum 210,000 pounds of thrust in vacuum, and it features a lengthened nozzle and extended tanks. The interstage connecting the Falcon 9’s first and second stages is also changed to accommodate the new Merlin vacuum nozzle, which has a center pusher to aid stage separation, according to space industry officials.

Another feature of the new-generation Falcon 9 is it will fly with condensed propellant, allowing engineers to load extra fuel into the rocket. Like earlier versions of the Falcon 9, the rocket consumes liquid oxygen and RP-1 fuel, a type of refined kerosene.

That works by chilling the liquid oxygen and RP-1 fuel mixture to colder temperatures, packing the propellant molecules closer together to free up room for additional fuel.

Musk said the densified liquid oxygen on the upgraded Falcon 9 is chilled to minus 340 degrees Fahrenheit, colder than typical launch-grade liquid oxygen at minus 298 degrees. The RP-1 fuel will fly at 20 degrees Fahrenheit, down from the room temperature 70-degree level more commonly used in rocketry.

He tweeted late Thursday the colder liquid oxygen was “presenting some challenges,” during that day’s static fire attempts, but Musk did not elaborate on the issues, adding that it was the first time a rocket would launch with oxidizer at such cold temperatures.

“There are a number of improvements in the rocket, and one of the things we’re doing for the first time — the first time I think anyone’s done it — is deeply cryogenic propellant,” Musk said in remarks Tuesday at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. “We’re sub-cooling the propellant, particularly the liquid oxygen because it’s two-thirds liquid oxygen, close to its freezing point, which increases the density quite significantly.

“The thrust is higher, we’ve improved the stage separation system, we stretched the upper stage of the rocket to add more propellant to that,” Musk said. “There are a number of other improvements in electronics. It’s, I think, a significantly improved rocket from the last one.”

The design modifications increase the rocket’s height by about 5 feet — to 229 feet — and boost the Falcon 9’s performance by about 30 percent, officials said.

The upgrades allow the Falcon 9 to lift heavier communications satellites into geostationary transfer orbit, and still have enough reserve propellant to attempt landing. Earlier missions with payloads going to such orbits flew in expendable mode and did not try for a controlled descent to an ocean-going barge in the Atlantic Ocean.

SpaceX was working on the upgraded rocket before the June launch failure, the first in 19 flights of the Falcon 9.

SpaceX’s two chief rivals — United Launch Alliance in the U.S. market and Arianespace in the international launch business — are paying attention to Sunday’s flight.

George Sowers, ULA’s vice president of advanced concepts and technologies, responded early Friday to Musk’s comments on Twitter regarding the issues supercooled liquid oxygen: “That’s why we don’t bother. Lots of complexity for little gain.”

Arianespace chief executive Stephane Israel told Spaceflight Now in an interview that he wishes SpaceX the best on the return-to-flight mission.

“Launching can be tricky,” Israel said. “There was a former CEO of Arianespace and CNES — Frédéric d’Allest — a very impressive guy, who always said that in our business, it is a business where failure and success are the closest. One little thing can make a difference and change the outcome of the mission.

“Our main competitor has a huge backlog to deliver in the coming two years,” Israel said. “What will not be easy on their side will be to do three things at the same time: keep innovating; launch as often as possible; and not fail. This is their challenge. We have our own challenges obviously.”

The third objective of Sunday’s flight — classified as purely experimental — will be to recover the Falcon 9’s booster stage a few minutes after liftoff, perhaps at a landing pad near the eastern tip of Cape Canaveral leased by SpaceX from the U.S. Air Force.

SpaceX has not officially disclosed whether the rocket will head for the landing pad on the Florida coast or the company’s landing barge, or drone ship, positioned in the Atlantic Ocean.

Falcon 9 boosters have attempted controlled landings on the drone ship before, using three brief ignitions of a subset of its nine engines to guide itself to the barge and slow down to a vertical descent as landing legs extend for touchdown.

The rocket has reached the drone ship both times it tried, but SpaceX has not stuck the landing. The rocket tipped over and broke apart in a fireball, and SpaceX executives have said the rocking motion of the football field-sized platform adds another challenge to the ocean landings, despite taking special measures with underwater control thrusters to keep the ship stable.

SpaceX is not the only space company vying for a reusable rocket.

Blue Origin, a firm founded by Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos, launched a suborbital rocket to the edge of space in November from West Texas and successfully landed it a few minutes later in a similar manner to SpaceX’s vertical descent method.

Bezos and Musk disagreed on whether landing the Falcon 9 or Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket is more technically daunting, but Bezos’ company chalked up the first-ever safe return of a commercial vehicle that took off under its own power and flew into space.

SpaceX hopes to retrieve a used rocket and run it through inspections and tests on the ground before reuse. If the booster could be recycled and flown again, SpaceX says launch costs will come down.

“With reusable rockets, we can reduce the cost of access to space by probably two orders of magnitude,” Musk said.

A notice sent to employees at the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station said SpaceX may attempt a landing at the spaceport, and it detailed road closures beyond those typically shut down for a launch, potentially due to the landing try.

A spokesperson for the Air Force’s 45th Space Wing, the unit responsible for the the Cape Canaveral launch range, declined comment on additional safety precautions that might be taken for the unprecedented rocket landing, if it occurs.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.