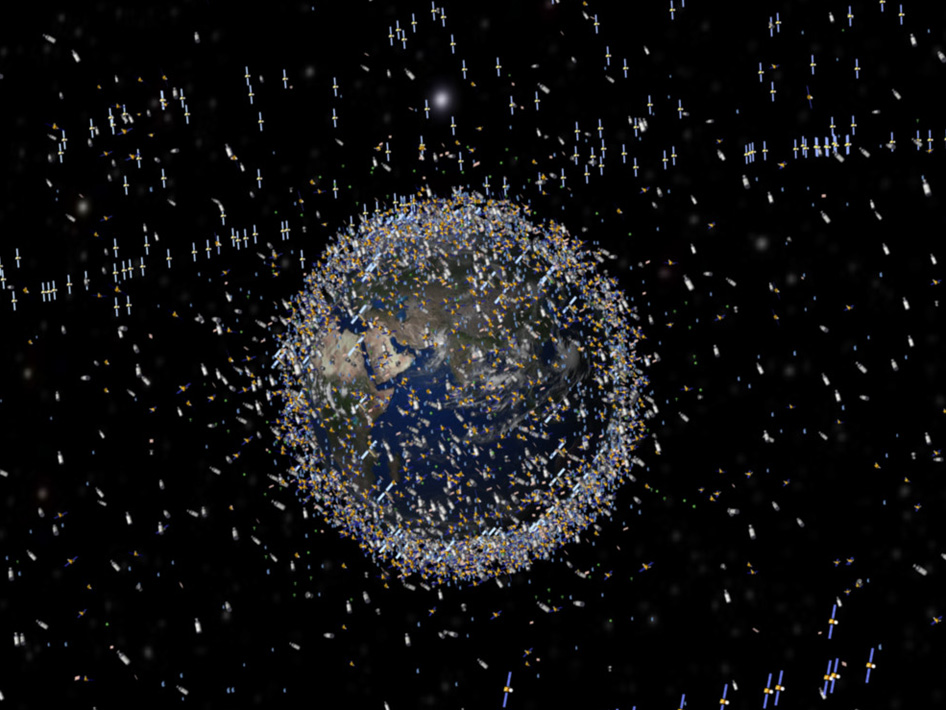

Two mystifying incidents last year involving separate Iridium communications satellites have experts wondering whether the spacecraft collided with tiny fragments of space junk.

Both satellites kept operating after inexplicably shedding debris, puzzling engineers who are concerned about the population of small objects in orbit that cannot be tracked by the U.S. Air Force’s network of sensitive radars and cameras.

Both events “illustrate how mysterious many of the debris phenomena in Earth orbit still remain,” according to an article in a quarterly report published by NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The U.S. Joint Space Operations Center detected 10 pieces of debris from the Iridium 47 satellite June 7, 2014. Some of the objects flew away from Iridium 47 at up to 80 meters per second — nearly 180 mph — into orbits almost 200 miles above the satellite, suggesting an explosion or collision triggered their creation.

Another Iridium spacecraft — Iridium 91 — produced four debris fragments Nov. 30, according to U.S. military tracking data.

“In contrast to the previous Iridium breakup, however, these pieces were produced with minimal delta velocity and remained in the vicinity to the parent spacecraft for some time,” NASA officials wrote.

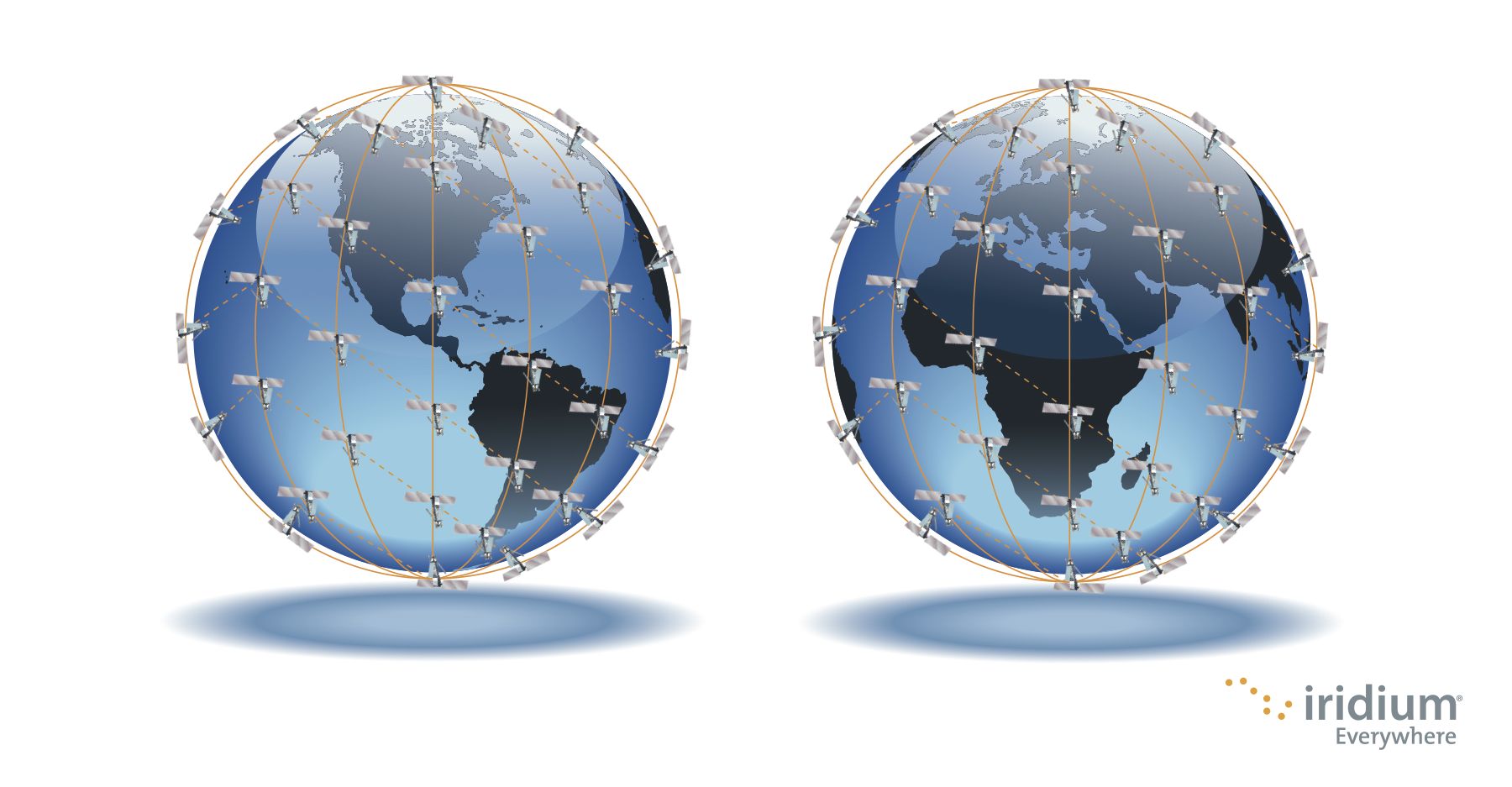

In both cases, the satellites showed no signs of a breakup and remain operational, according to Iridium Communications, a Virginia-based company that uses a fleet of spacecraft nearly 500 miles above Earth for mobile voice and data services.

NASA’s orbital debris experts said strikes from small bits of space junk could have caused either or both incidents. It is possible that Iridium 91, which generated less debris at slower speeds — may have cast off chunks of thermal insulation, according to the orbital debris report.

“The Iridium 47 event, however, clearly was due to some sort of high-energy event,” NASA experts wrote. “In the absence of evidence of an explosion on board the spacecraft, a collision with a piece of untracked debris is the most likely culprit.”

At orbital speeds, an impact with a sizable piece of space junk can be catastrophic.

If something hit one of the satellites, it would not be the first time an Iridium spacecraft had a run-in with space junk.

The Iridium 33 spacecraft collided with a dead Russian military satellite in February 2009, destroying both craft and polluting busy space traffic lanes with thousands of new pieces of debris in low Earth orbit.

The Iridium constellation is located at the same altitude as much of the debris left over from the 2009 crash and a Chinese anti-satellite weapons test that littered Earth orbit with another set of satellite shards in 2007.

Iridium operates the largest network of commercial satellites in orbit, with 66 interconnected spacecraft to beam global phone calls and data transfers between the company’s customers, which include military troops, ships at sea, media organizations, and transport companies.

Since the 2009 collision, the Air Force has disseminated warnings of possible satellite conjunctions — or close flybys — with commercial and international satellite operators, providing the owners a chance to maneuver operational spacecraft out of the way and avoid another collision.

The U.S. military’s radars and optical sensors can see anything larger than a basketball, or about 23,000 objects in orbit, less than 5 percent of the total number of tiny junk fragments believed to be circling Earth.

The holes in coverage mean small bits of space debris roam undetected.

The Air Force and Lockheed Martin are working on a modernized tracking system called the Space Fence, which will detect objects as small as a softball at an altitude of 1,200 miles, giving officials the ability to monitor more than 200,000 satellites, derelict rockets, and other manmade debris.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.