The European Space Agency’s Venus Express spacecraft has run out of fuel and will burn up in the atmosphere of Venus in January after a successful eight-year mission.

Ground controllers lost contact with Venus Express on Nov. 28 after a planned maneuver to raise the altitude of the craft’s orbit around Venus in hopes of keeping the mission going into 2015.

Håkan Svedhem, ESA’s Venus Express project scientist, said mission control has received intermittent telemetry from the spacecraft since late November. The data signature indicates the orbiter is in a spin and can only contact Earth when its antennas happen to be pointing the right direction.

Complicating matters, Venus is near the farthest point from Earth as the planets orbit around the sun, so radio signals from Venus Express are very week, Svedhem said.

Venus Express was programmed to execute a series of rocket burns to boost its orbit from Nov. 23 to Nov. 30 to keep the spacecraft from entering the Venusian atmosphere.

“The available information provides evidence of the spacecraft losing attitude control most likely due to thrust problems during the raising maneuvers,” said Patrick Martin, ESA’s Venus Express mission manager. “It seems likely, therefore, that Venus Express exhausted its remaining propellant about half way through the planned maneuvers last month.”

Officials knew the fuel and oxidizer tanks aboard Venus Express were running low, but spacecraft do not carry a fuel gauge, so engineers were not sure how much propellant was left on the orbiter.

“It is difficult to quantify the probability, but I would say that it is very likely that the fuel in the tanks is at least so much depleted that we sometimes get gas bubbles in the fuel lines,” Svedhem said in an email to Spaceflight Now. “There might still be some limited amount of fuel in the tanks but this is not accessible.”

Without propellant to maintain its altitude, Venus Express will succumb to atmospheric drag and fall out of orbit some time around mid-January, Svedhem said.

The probe will be crushed by the pressure of the Venusian atmosphere, disintegrating in a ball of plasma dozens of miles above the planet.

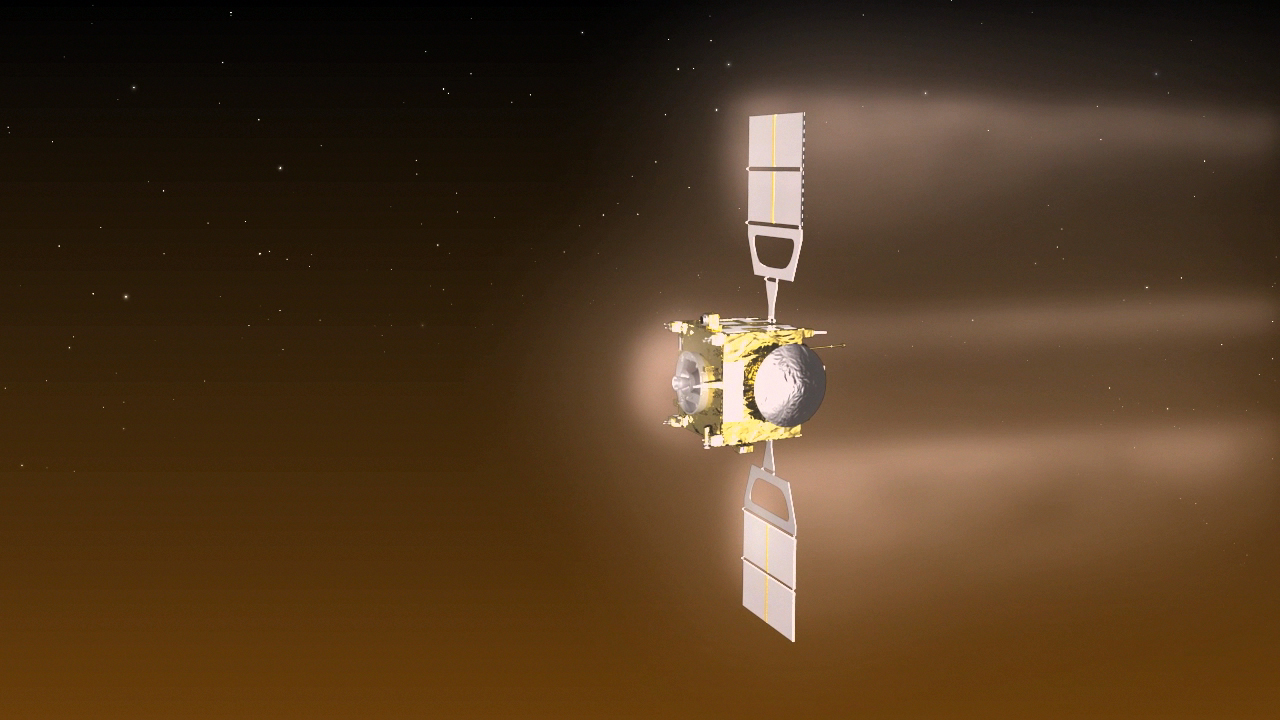

The spacecraft arrived at Venus in April 2006 after five-month cruise from Earth, entering an egg-shaped orbit for a planned 500-day mission.

ESA granted extra funding to continue the mission, including a final tranche of money approved in November to extend Venus Express operations into 2015 until it exhausted its fuel supply.

“After over eight years in orbit around Venus, we knew that our spacecraft was running on fumes,” said Adam Williams, ESA’s acting Venus Express spacecraft operations manager. “It was to be expected that the remaining propellant would be exhausted during this period, but we are pleased to have been pushing the boundaries right down to the last drop.”

Controllers used the last bit of fuel inside the spacecraft to move its orbit closer to Venus in from May to July, exploring deeper inside the Venusian atmosphere and gathering data on aerobreaking, a technique that future missions could use to shape their orbits around planets like Venus.

Venus Express spent most of its mission circling the planet in an orbit with a point closest to Venus about 120 miles (200 kilometers) above its surface. The orbit typically took the spacecraft 41,000 miles (66,000 kilometers) from Venus at its highest altitude.

The aerobreaking campaign this year involved flying Venus Express as low as 80 miles (130 kilometers) above the planet. When the experiments were finished, engineers raised the low point of the craft’s orbit to an altitude of about 285 miles (460 kilometers).

But the orbit naturally decayed and Venus Express fell closer to the upper reaches of the atmosphere, causing officials to decide to boost its orbit again in a bid to extend its mission by a few months.

It turns out there was not enough propellant left in the probe’s tanks to complete the orbit-raising maneuvers.

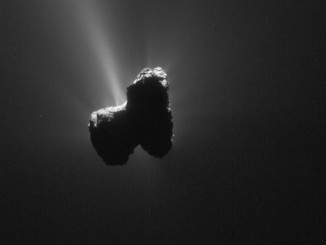

Venus Express was built out of spare parts from ESA’s Mars Express and Rosetta missions and launched in November 2005. ESA developed and launched the low-budget mission for 220 million euros, or about $270 million, at 2005 values.

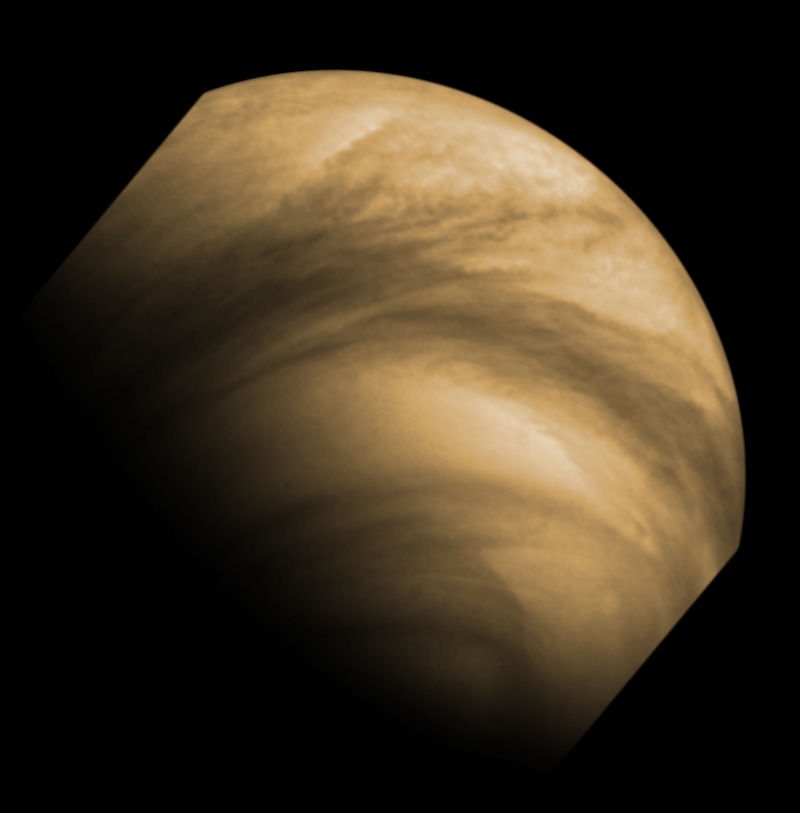

Scientists say the mission found evidence of lava flows on Venus indicating active volcanism within the last 2.5 million years. It also sensed fluctuations in concentrations of sulphur dioxide in the upper atmosphere, a finding that could be explained by volcanic activity.

The orbiter’s instruments measured wind speeds rose in the smothering Venusian atmosphere over a six-year period.

The spacecraft discovered that a day on Venus — which lasts 243 Earth days — had shortened by six-and-a-half minutes since NASA’s Magellan mission measured the planet’s rotation more than 20 years ago.

Data from Venus Express also support the theory that the planet was once more hospitable for life, with measurements indicating Venus once harbored significant water, perhaps enough to fill oceans on its surface, according to an ESA press release.

“During its mission at Venus, the spacecraft provided a comprehensive study of the planet’s ionosphere and atmosphere, and has enabled us to draw important conclusions about its surface,” Svedhem said in an ESA press release. “While the science collection phase of the mission is now complete, the data will keep the scientific community busy for many years to come.”

With the end of the Venus Express mission, no more spacecraft are operating at Earth’s sister planet.

Japan’s Akatsuki mission is due to arrive at Venus in November 2015 after missing a chance to enter orbit there in late 2010. Japanese officials blamed the 2010 failure on a glitch in the probe’s main engine, and engineers plan to use smaller thrusters to help Venus capture the spacecraft in orbit.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.