Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo rocket plane disintegrated in mid-air after two tail stabilizers prematurely extended, federal investigators said Sunday, a discovery that could shift the focus of the probe into Friday’s fatal crash away from the craft’s rocket motor.

But the National Transportation Safety Board’s acting chairman Christopher Hart cautioned against jumping to conclusions.

“What I’m about to say is a statement of fact and not a statement of cause,” Hart said. “We are a long way from finding cause. We still have months and months of investigation to do, and there’s a lot that we don’t know. We have extensive data sources to go through.”

An analysis of telemetry and video recorded aboard the doomed space plane has revealed SpaceShipTwo’s novel braking system deployed earlier than designed.

The rocket plane’s rear-mounted feathering system is supposed to extend before the ship descends back into the atmosphere from space, slowing SpaceShipTwo’s speed and putting the craft into a belly-down position during re-entry.

But SpaceShipTwo’s twin tail booms rotated upward seconds after it fired a hybrid rocket motor following a drop from Virgin Galactic’s WhiteKnightTwo carrier plane 50,000 feet above California’s Mojave Desert.

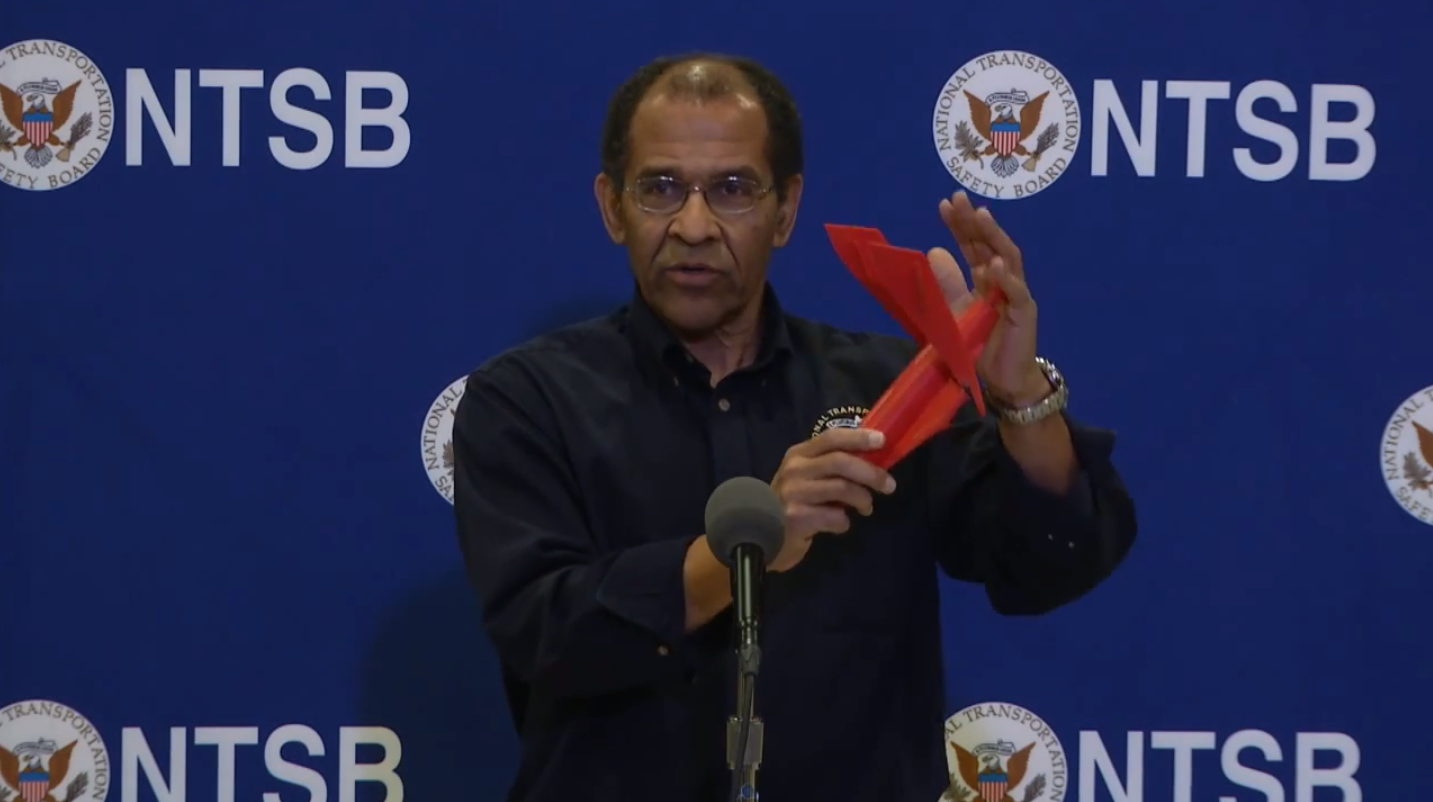

The NTSB is leading the investigation into Friday’s crash, and Hart said Sunday that ShipShipTwo’s co-pilot moved a lever inside the space plane’s cockpit to unlock the tail feathers, which are normally pointed toward the rear of the vehicle when it flies under rocket power.

The co-pilot on Friday’s flight — 39-year-old Michael Alsbury — died in the accident. Alsbury’s co-workers at Scaled Composites, builder of SpaceShipTwo, have established a memorial fund.

Pilot Peter Siebold, 43, was able to get free of the space plane and parachute to the ground. He was hospitalized with serious injuries.

The rocket’s hybrid rocket motor, consuming a mix of nitrous oxide and a plastic-based solid fuel mix, ignited a few seconds after SpaceShipTwo’s release from the carrier aircraft. Friday’s test flight marked the first time the rocket motor was used on SpaceShipTwo since Virgin Galactic switched from a rubber-based to a plastic-based fuel.

“About nine seconds after the engine ignited, the telemetry data showed us that the feather parameters changed from lock to unlock,” Hart said.

According to Hart, a camera mounted inside SpaceShipTwo’s cockpit showed Alsbury move a handle to unlock the feather system as the rocket plane passed Mach 1 — the speed of sound.

Such action on a SpaceShipTwo flight is not expected until the rocket plane reaches Mach 1.4, Hart told reporters in a press conference Sunday night in Mojave, Calif.

“Normal launch procedures are that after the release, the ignition of the rocket and acceleration, that the feathering devices are not to be moved — the lock/unlock lever is not to be moved into the unlock position — until the acceleration up to Mach 1.4. Instead, as indicated, that occurred (at) approximately Mach 1.0,” Hart said.

The tail booms extended after they were unlocked, even though they were not commanded to do so, Hart said. SpaceShipTwo’s pilots normally must unlock the feathers, then send a separate command to move the tail booms into position for descent.

“This was what we would call an uncommanded feather, which means the feather occurred without the feather lever being moved into the feather position,” Hart said.

“After it was unlocked, the feathers moved into the deployed position, and two seconds later we saw disintegration,” Hart said.

“Shortly after the feathering occurred, the telemtry data terminated and the video data terminated,” Hart said.

The video embedded below shows how SpaceShipTwo’s feathering system works from a camera attached to one of the ship’s tail booms on a previous flight.

The performance of SpaceShipTwo’s rocket motor, which was flying for the first time with a new type of propellant, was normal up until the extension of the rocket plane’s tail feathers, according to Hart.

Investigators combing the five-mile-long debris field have located SpaceShipTwo’s rocket motor and propellant tanks, which were found intact and show no sign of burn-through or breaching, according to Hart. Some of the rocket plane’s wreckage has been moved into hangars for examination.

Six video cameras and six data recorders on-board SpaceShipTwo will also help the investigation, Hart said, along with footage from the space plane’s carrier plane, ground-based imagers, and eyewitness interviews. Investigators also planned to interview Siebold, the surviving pilot.

When asked if Sunday’s revelation would put the focus of the investigation on pilot error, Hart said the NTSB is not ruling anything out.

“We are looking at a number of possibilities, including that possibility,” Hart said.

“I want to emphasize that we have not determined the cause,” Hart said. “I am not stating that this is the cause of this mishap. We have months and months of investigation to determine what the cause was. We’ll be looking at training issues, we’ll be looking at was there pressure to continue testing, we’ll be looking at safety culture. We’ll be looking at the design (and) the procedure. We’ve got many, many issues to look into much more extensively before we can determine the cause.

“There is much that we don’t know, and our investigation is far from over.”

Friday’s test flight was the next step to realize Virgin Galactic’s plans to start operational service with SpaceShipTwo by next spring, ferrying paying passengers to a speed three-and-a-half times the speed of sound at an altitude of more than 100 kilometers, or 62 miles, above Earth — the internationally-recognized boundary of space.

Passengers at that altitude could unstrap from their seats and float around the rocket plane’s six-person cabin for a few minutes before gliding back to the ground for landing on a runway.

Virgin Galactic issued a statement Sunday defending the company’s safety record and urging against speculation on the cause of Friday’s mishap.

“At Virgin Galactic, we are dedicated to opening the space frontier, while keeping safety as our ‘North Star’. This has guided every decision we have made over the past decade, and any suggestion to the contrary is categorically untrue,” the company said.

“We have the privilege to work with some of the best minds in the space industry, who have dedicated their lives to the development of technologies to enable the continued exploration of space,” the company said. “All of us at Virgin Galactic understand the importance of our mission and the significance of creating the first ever commercial spaceline. This is not a mission that anyone takes lightly.”

The company, founded by Virgin Group’s Richard Branson, said it would not comment on the investigation while the NTSB is doing its work.

“Now is not the time for speculation,” the company said. “Now is the time to focus on all those affected by this tragic accident and to work with the experts at the NTSB, to get to the bottom of what happened on that tragic day, and to learn from it so that we can move forward safely with this important mission.”

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.