Boeing said Wednesday it has turned down an offer from Aerojet Rocketdyne to buy United Launch Alliance, a Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture that operates the Atlas and Delta rocket fleets.

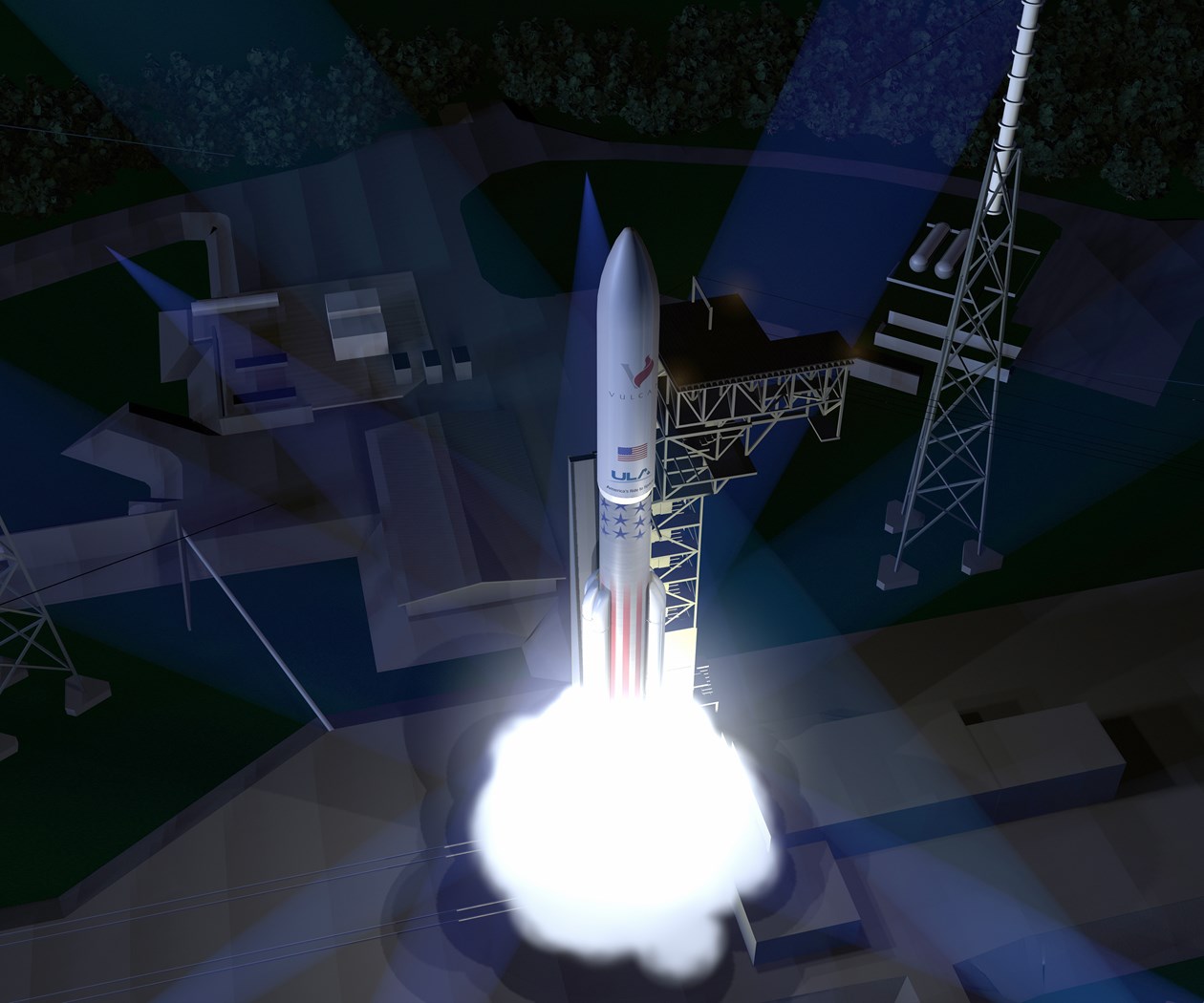

The decision keeps ULA’s plan to select a new engine for the company’s next-generation Vulcan rocket some time next year. Aerojet Rocketdyne and Blue Origin are in the running to be the engine supplier.

The unsolicited offer, reportedly worth $2 billion, was made by the company that builds rocket engines for ULA’s Delta 4 launcher and Atlas 5 upper stage.

“With regard to reports of an unsolicited proposal for ULA, it is not something we seriously entertained for a number of reasons,” said Todd Blecher, a spokesperson for Boeing’s defense and space division, in an email to Spaceflight Now. “Boeing is committed to ULA and its business, and to continued leadership in all aspects of space, as evidenced by the agreement announcement last week with Blue Origin.”

ULA says it prefers an engine made by Blue Origin, a company founded by Amazon.com chief Jeff Bezos, to power the company’s next-generation Vulcan rocket. Aerojet Rocketdyne is working on its own engine called the AR1, but ULA officials say its development is two years behind Blue Origin’s.

Officials announced an agreement Sept. 10 to expand Blue Origin’s engine production capability to ramp up for the Vulcan program.

“Under the agreement, Blue Origin will expand its existing BE-4 production capability already established at its Kent, Washington, development facility to accommodate the initial production rate needed for the Vulcan launch vehicle,” said Jessica Rye, a ULA spokesperson.

The BE-4 engine in development by Blue Origin is nearing its critical design review, a milestone in which the powerplant’s design will be frozen and managers will deem it ready for hardware production.

The AR-1 engine by Aerojet Rocketdyne is closing in on its preliminary design review, Bruno wrote in a post to his Twitter account.

Both use staged-combustion designs, a more efficient class of rocket engines not currently manufactured in the United States.

.@dougcameron Continuing to carry both engines. Because BE4 is coming up on CDR (vs PDR for AR1), it is entering its long lead mfg window

— Tory Bruno (@torybruno) September 10, 2015

United Launch Alliance’s corporate parents are approving quarterly tranches of funding for the Vulcan rocket, eyeing concerns about the future supply of Russian-made RD-180 engines for the Atlas 5 rocket’s first stage booster.

Under pressure from newcomer SpaceX, ULA is aiming for launch costs of less than $100 million per Vulcan flight, and the company plans to roll out a scheme in the 2020s to capture booster engines after launch for refurbishment and reuse. An upgraded upper stage to replace the Centaur rocket is also in ULA’s long-term plans.

First will come a basic Vulcan configuration relying on the same Centaur stage, and similar solid rocket boosters and payload shrouds from the Atlas 5. The new item will be a redesigned first stage core with an American-made engine.

ULA’s designers are working on two versions of the company’s Atlas 5 replacement rocket: One with at least a 5.1-meter (16.7-foot) diameter core stage with two BE-4 main engines, and another with a slimmer 3.8-meter (12.5-foot) wide first stage with a pair of AR1 powerplants.

The wider stage, based on tanks flown on ULA’s Delta 4 rocket, is needed to accommodate methane fuel for the BE-4 engines, which each generate about 550,000 pounds of thrust at full throttle. The AR1 burns rocket-grade kerosene fuel, with higher density than methane, and can be flown with a booster stage the same diameter as the Atlas 5, Bruno said.

But the version with AR1 engines would feature a lengthened core stage from the tanks flying on the Atlas 5, and a feed line for liquid oxygen coursing down the center of the rocket. The Atlas 5’s liquid oxygen fuel plumbing runs outside the first stage to reach the rocket’s RD-180 engine.

ULA has only released artists concepts and promotional materials for the Vulcan configuration with BE-4 engines.

Blue Origin founder Bezos told reporters this week his company’s engineers have worked on the BE-4 engine for more than three years. It is an evolution of Blue Origin’s BE-3 engine, which powers the company’s suborbital New Shepard launcher designed for space tourism.

“The BE-4 engine has a lot of unique characteristics, technically, but I think the most unique feature of the BE-4 engine is that it’s fully funded,” Bezos said. “It’s not something you see with rocket engine programs very often.”

With a net worth of nearly $50 billion, according to Forbes, Bezos established Blue Origin in 2000 and has personally funded the bulk of the company’s development projects.

“Our approach on this is very simple, which is we stay heads down focused on the technology,” Bezos said Tuesday. “We’re going to build the best 21st century engine that we can for ULA. Ultimately, they’ll make the decision about what they want to do, but we’re going to work our butts off to give them a great engine.”

Blue Origin President Rob Meyerson said in April the BE-4 engine’s development will finish in 2017 after full-scale testing in late 2016 at the company’s West Texas test facility. That schedule is in line with ULA’s plans to conduct the first test launch of the Vulcan rocket in 2019.

Tests of the engine’s powerpack and propellant injectors are ongoing, Meyerson said.

More than 60 staged-combustion tests of the BE-4 engine are already in the books, Bezos said in a statement in the Sept. 10 announcement on BE-4 engine production in Washington.

Bezos visited Cape Canaveral on Tuesday to announce plans to set up a commercial rocket factory and launch pad for Blue Origin’s own orbital launch vehicle, which will fly with BE-4 engines and could eventually be a competitor for ULA’s Vulcan.

He did not disclose details on Blue Origin’s launcher.

“If you look at the reliability track record that (ULA) has had, it’s truly extraordinary, and when you look at some of the national security payloads, that is the No. 1 factor,” Bezos said. “Space is pretty big. There are a lot of opportunities, and there’s room for multiple winners. We’re going to work our butts off to make sure that the BE-4 engine is the best possible engine for United Launch Alliance.”

Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR1 engine is two years behind Blue Origin’s current schedule.

Julie Van Kleeck, the company’s vice president of space programs, told Spaceflight Now in an interview that ULA and Aerojet Rocketdyne submitted a joint proposal to the U.S. Air Force, which plans to dole out a combined $160 million to multiple contractor teams to advance work on new U.S. rocket engines.

The Air Force is expected in the coming weeks to select up to four winners from the companies that submitted bids, a list industry officials expect to include Blue Origin, Orbital ATK, and perhaps SpaceX, which is working on its own methane-fed Raptor rocket engine for a new series of rockets bigger than the existing Falcon family.

Congress wants the Air Force to cease use of the RD-180 engine by 2019, but military leaders say that schedule is tight. There is disagreement between the House and the Senate on how many RD-180 engines can be used for future military launches, with the Senate holding to a lower number.

The disparity has raised complaints from the Air Force and ULA that limiting RD-180 engine use would give SpaceX control of the military launch market, which has been dominated by ULA since the merger of the Atlas and Delta rocket programs in 2006. The Air Force policy’s is to have two independent rockets to loft the military’s most critical satellite payloads, and ULA has announced it plans to retire the single core “medium” version of its Delta 4 launcher — which has all U.S. propulsion — in 2018 or 2019 because it is not cost-competitive with the Falcon 9 or Atlas 5.

“We’ll be providing an offering in conjunction with ULA,” Van Kleeck said in August. “We’re on schedule. We’re investing pretty heavily in the engine right now, and we’re on schedule to get to a preliminary design review.”

Van Kleeck said testing of sub-scale engine hardware is going well, with some components set to undergo a full mission duty cycle test this winter. Aerojet Rocketdyne is working on the AR1 engine with internal company funds, but the engine’s planned readiness date in 2019 hinges on outside support.

“We’re still looking to qualify the engine and certify it in 2019,” she said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.