President Biden unveiled the deepest ever look into the distant universe Monday with the release of the first full-color science image from the James Webb Space Telescope, showing thousands of faint galaxies and countless stars shining like lampposts in a tiny patch of the southern sky.

The image shows SMACS 0723, a massive galaxy cluster visible from the Southern Hemisphere with immense gravity that can bend the light from much fainter background galaxies like a magnifying glass. Called gravitational lensing, this phenomenon can amplify the already powerful imaging sensitivity of a telescope like Webb, the largest observatory ever put into space.

The result presented in the image released Monday was nothing short of spectacular. See a higher-resolution view of the image.

“If you held a grain of sand on the tip of your finger at arm’s length, that is the part of the universe that you’re seeing, just one little speck of the universe,” said Bill Nelson, NASA’s administrator, in a briefing at the White House with President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. “And what you’re seeing there are galaxies, you’re seeing galaxies that are shining around other galaxies whose light has been bent, and you’re seeing just a small little portion of the universe.”

There are thousands of galaxies in view around and behind SMACS 0723, including the faintest objects ever observed in infrared light.

“We’re looking back more than 13 billion years,” Nelson said. “Light travels 186,000 miles per second, and that light that you are seeing on one of those little specks has been traveling for over 13 billion years.”

The early unveiling at the White House, announced late Sunday, came one day before the long-planned release date for the first Webb science images Tuesday, when officials from NASA, the European Space Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, and other research institutions will reveal the observatory’s first glimpse of a range of cosmic wonders.

“As an international collaboration, this telescope embodies how America leads the world, not by the example of our power but by the power of our example,” Biden said. “These images are going to remind the world that America can do big things and remind the American people, especially our children, that there’s nothing beyond our capacity.”

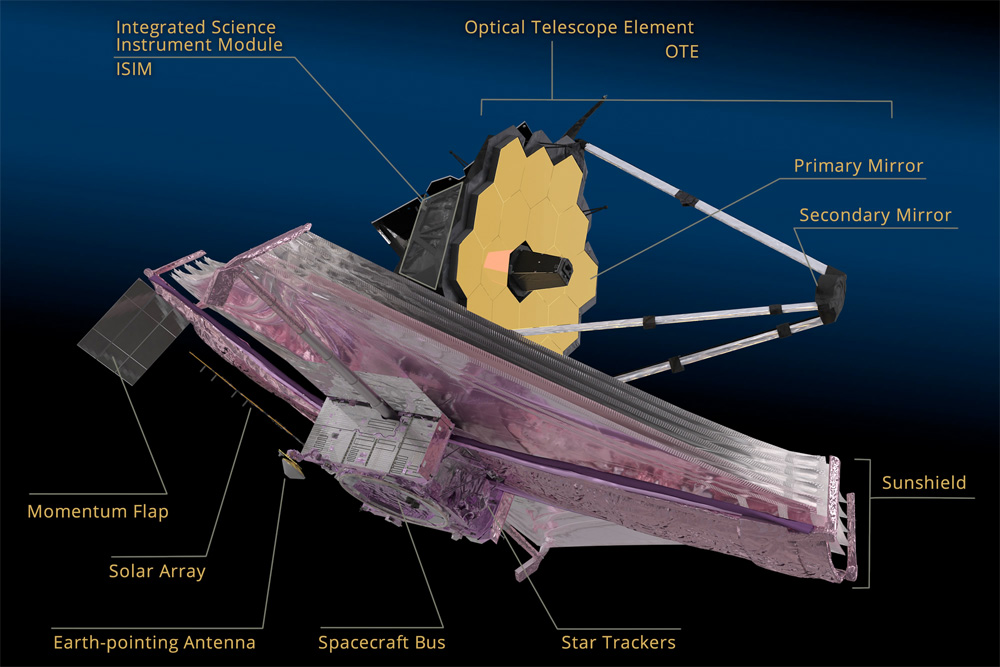

After more than 20 years of design, development, assembly, and testing, the James Webb Space Telescope launched on Christmas Day on top of a European Ariane 5 rocket, and arrived at its operating orbit nearly a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth in January. Since launch, the $10 billion observatory opened its mirror and sunshield, allowing its instrument detectors to cool down to cryogenic temperatures, not far above absolute zero.

Over the last few months, ground teams have calibrated Webb’s four science instruments and aligned the telescope’s mirror segments. The last of the telescope’s 17 observing modes was declared ready for scientific operations Monday.

“We stuck to it, and it got made, and it’s there,” said Mark McCaughrean, a senior advisor at ESA and an interdisciplinary scientist on Webb. “Not only did it survive the launch, and it got into space, and not only did it deploy, but it performs. There are reasons to think it’s actually performing better than expectations.”

Webb’s segmented primary mirror — with a diameter of 21.3 feet (6.5 meters) — is the largest ever put into space. The mirror’s light collecting power, coupled with its sensitive, super-cold detectors, allow Webb to peer deeper into the universe — and farther back in time — than humans have ever seen before.

Before Webb, the Hubble Space Telescope was the benchmark for space-based astronomical observatories. Launched in 1990 with a mirror a third the size of Webb’s, Hubble’s suite of instruments observing in ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared light wooed astronomers with views of distant galaxies, colorful clouds of gas in star-forming nebulas, and provided measurements of the expansion rate of the universe.

Before and after.

Here's what the Hubble Space Telescope — until now the benchmark in space-based astronomy — saw of galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 in a sliver of the southern sky.

Continue watching to see the new view from the James Webb Space Telescope.https://t.co/WJmoIqMAMl pic.twitter.com/f8W2l5ftUV

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) July 12, 2022

Astronomers have used Hubble to stare deep into cosmic history with a series of “deep field” images, each showing thousands of previously-unseen distant galaxies in a small section of the sky. One of the images, called the Hubble Extreme Deep Field, was released by NASA in 2012, revealing some 5,500 galaxies of all shapes and sizes by combining observations with two of Hubble’s instruments with a total exposure time of 23 days.

The oldest galaxies in the Hubble Extreme Deep Field were seen as they were 13.2 billion years ago, some 500 million years after the Big Bang birthed the universe. Webb’s First Deep Field — the SMACS 0723 image — was unveiled Monday by President Biden.

The distant galaxies magnified through the lens of the SMACS 0723 galaxy cluster have structures never seen before according to NASA.

“Researchers will soon begin to learn more about the galaxies’ masses, ages, histories, and compositions, as Webb seeks the earliest galaxies in the universe,” NASA said.

Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera, or NIRCam, instrument collected observations to create the composite image released Monday. The exposures totaled 12.5 hours, exceeding the depth achieved by Hubble in weeks of observations.

“This is going deeper (than Hubble),” McCaughrean said. “We’re seeing fainter in 12-and-a-half hours than you could see in an entire month of observing with Hubble. That’s party because it’s big telescope. Obviously, we collect more light. But the real trick here is that we’re in the infrared now.”

The expansion of the universe stretches out light into longer wavelengths, making the shine from the oldest stars and galaxies invisible to Hubble’s instruments. Longer exposure times by Webb will allow the telescope to gather more light and see even dinner, more distant, more ancient galaxies.

“This is just the beginning,” McCaughrean said. “If we can do 12 hours, we can do 24 hours, we can do two weeks, we can do a month, and that means that we can get the goals that we set for ourselves.”

Scientists have said Webb, with its improved light collecting power and infrared instruments better tuned to the red-shifted light from the ancient universe, could see the first generation of stars and galaxies that shined just 100 million to 200 million years after the Big Bang. Elements fused in those objects helped seed the universe of today.

But that’s not all Webb can do.

“This telescope is so powerful that if you were a bumble bee 240,000 miles away, which is the distance between the Earth and the moon, we will be able to see you,” said John Mather, the mission’s senior project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, before Webb’s launch.

“So what are we going to do with this great telescope? We’re going to look at everything there is in the universe that we can see.”

That runs the gamut from the most distant galaxies in the cosmos, to planets, moons, asteroids, and comets in our own solar system. Webb will be able to observe everything from Mars out, seeing details undetected by every other space observatory since Galileo revolutionized astronomy with his first telescope in 1609.

Webb will see through clouds of dust to study star-forming regions opaque to telescopes like Hubble. The light collecting power of Webb will also allow scientists to measure the chemical make-up of atmospheres on planets around other stars, revealing for the first time which alien worlds might be habitable for life.

Scientists dreamed up the mission that would become Webb in the 1990s, and NASA awarded a contract to Northrop Grumman in 2002 to oversee construction of the observatory. After a quarter-century, Webb is ready for service, beginning a science mission that could last 20 years, assuming nothing breaks and controllers can conserve fuel savings enabled by a near-perfect launch in December.

The arc of Webb’s mission could span more than two generations, from the start of development until it runs out of fuel. And the mission’s science data archive will live on.

“In a secular way, we built a cathedral,” McCaughrean said. “And it’s not just for us to go into, it’s for everybody else to enjoy.”

The SMACS 0723 galaxy cluster was one of five cosmic targets selected to be part of the first batch of Webb observations released to the public.

Here’s a list from NASA of the remaining four targets scheduled for release Tuesday:

- Carina Nebula: The Carina Nebula is one of the largest and brightest nebulae in the sky, located approximately 7,600 light-years away in the southern constellation Carina. Nebulae are stellar nurseries where stars form. The Carina Nebula is home to many massive stars several times larger than the Sun.

- WASP-96b (spectrum): WASP-96b is a giant planet outside our solar system, composed mainly of gas. The planet, located nearly 1,150 light-years from Earth, orbits its star every 3.4 days. It has about half the mass of Jupiter, and its discovery was announced in 2014.

- Southern Ring Nebula: The Southern Ring, or “Eight-Burst” nebula, is a planetary nebula – an expanding cloud of gas surrounding a dying star. It is nearly half a light-year in diameter and is located approximately 2,000 light-years away from Earth.

- Stephan’s Quintet: About 290 million light-years away, Stephan’s Quintet is located in the constellation Pegasus. It is notable for being the first compact galaxy group ever discovered in 1787. Four of the five galaxies within the quintet are locked in a cosmic dance of repeated close encounters.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.