NASA says a faulty memory chip was the cause of a problem that forced technicians to swap out an engine control computer on the first Space Launch System rocket late last year, but the issue is not a constraint for an upcoming SLS fueling test or launch later this spring.

The engine controller failed to reliably power up during testing in November, and managers ordered ground teams to swap out the computer inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center in December.

Engineers took the problematic computer to an offsite location for testing. The investigation determined a faulty memory chip in the computer prevented it from starting up as designed, according to NASA.

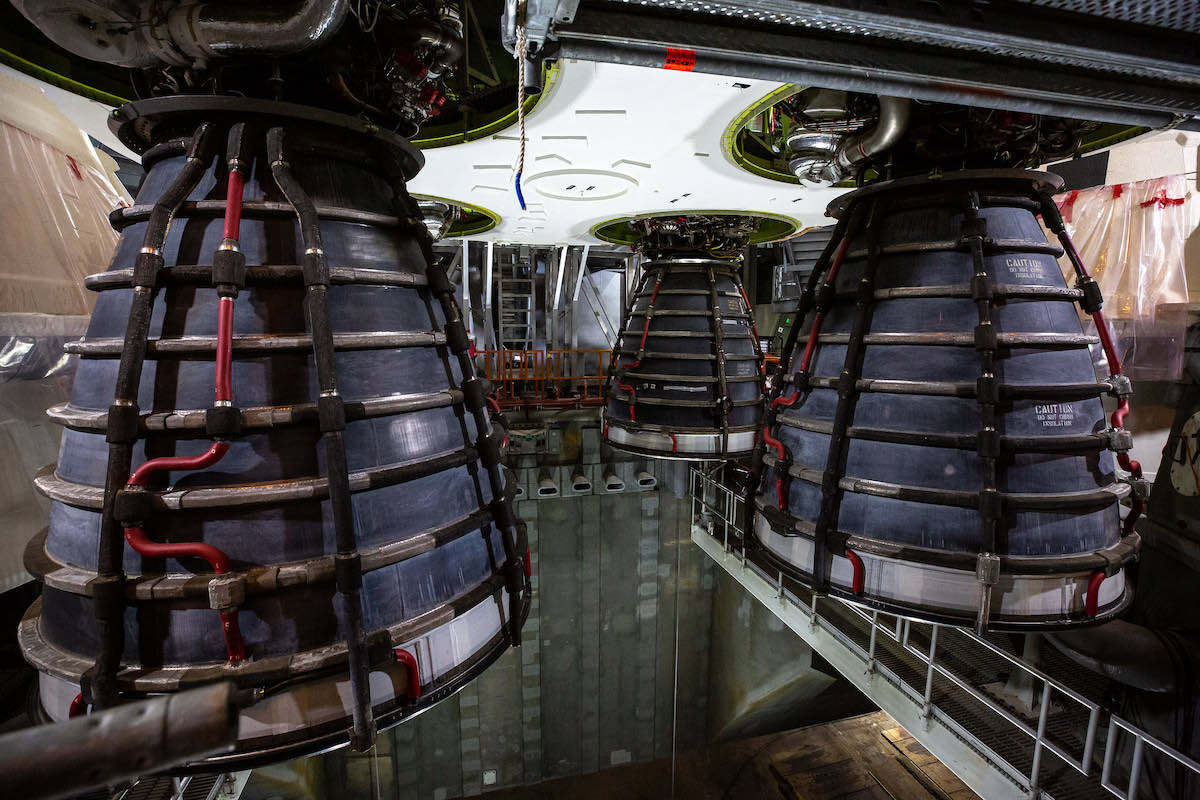

The SLS engine controllers, made by Honeywell, is about the size of a dorm room refrigerator. The computers relay commands between the SLS flight computer and the core stage’s four Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-25 engines, regulating thrust and fuel mixture ratio while monitoring the engine’s health and status.

The replacement engine controller installed on Engine No. 4 in December is working well, officials said. And there’s no indication of faulty memory chips on the controllers on the other three engines, meaning there are no “related constraints” ahead of the rocket’s rollout to the launch pad next month for a fueling test, or the SLS test flight later this spring, NASA said.

“All four engine controllers performed as expected during power up, as part of the Artemis 1 core stage engineering tests,” NASA said in an update posted Feb. 18.

The memory chip blamed for the computer start-up glitch is only used during the power-up sequence, and doesn’t impact any of the controller’s functions once turned on, NASA said.

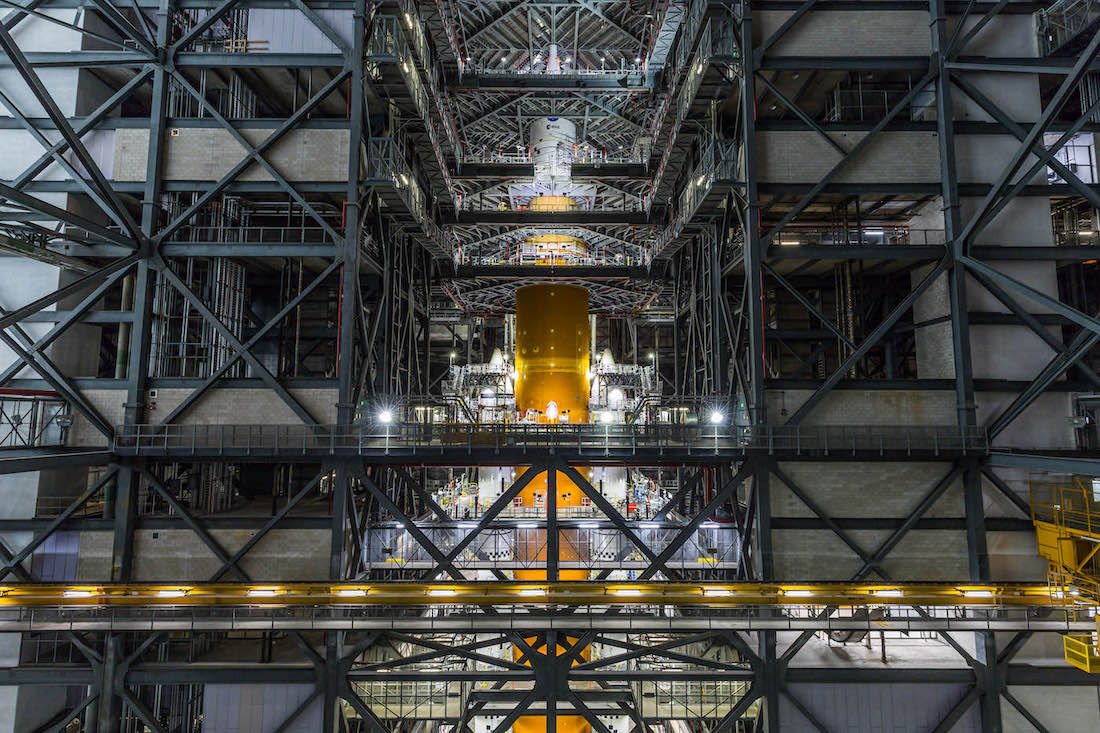

Ground teams at Kennedy Space Center are competing diagnostic testing and hardware closeouts on the Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft ahead of liftoff on the Artemis 1 mission, an unpiloted demonstration flight around the moon. The Artemis 1 mission, set to last at least three weeks, will place the Orion capsule in orbit around the moon for a shakedown cruise before four astronauts fly to the moon on the Artemis 2 mission in 2024.

The Orion spacecraft will return to Earth for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California.

Other work ongoing inside the Vehicle Assembly Building includes testing of the flight termination system, which would be used to destroy the rocket if it veers off its pre-approved flight corridor. Technicians are also installing instrumentation on the Space Launch System’s two solid rocket boosters.

The two side-mounted boosters and four RS-25 core stage engines — all using recycled hardware from the space shuttle program — will generate 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, more than the Saturn 5 moon rocket from the Apollo program.

The 322-foot-tall (98-meter) rocket will roll out of High Bay 3 and emerge from the Vehicle Assembly Building next month on a journey to launch pad 39B for a wet dress rehearsal. The practice countdown will culminate in loading of cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid hydrogen into the Space Launch System before concluding at T-minus 10 seconds, just before engine ignition.

The rocket will return to the VAB for further inspections and closeouts, then will roll back to pad 39B about a week before the target launch date.

NASA has not announced a launch date for the mission, but the agency is expected to target launch opportunities in April or May. Officials gave up on launch periods February and March after the engine controller problem, and to allow additional time for testing and closeouts ahead of the wet dress rehearsal.

An official target launch date will be set after the wet dress rehearsal, according to NASA. Agency officials plan to update the media on SLS launch preparations in a briefing Thursday.

The SLS test flight is a milestone in a decade-long development that started in 2011, when Congress ordered NASA to design and build a gigantic rocket using technology left over from the agency’s retired fleet of space shuttles. At that time, NASA officials hoped to launch the first SLS test flight in 2017, but the mission is now running more than four years late.

The main near-term aim of the Artemis program is to land astronauts on the moon, including the first woman and person of color to explore the lunar surface. Humans haven’t visited the moon since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. Eventually, NASA wants to establish outposts in lunar orbit and on the moon’s surface to pave the way for future expeditions to Mars.

The Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft are central to those plans, along with a commercial human-rated lander to ferry astronauts to and from the lunar surface. NASA last year selected SpaceX to develop and build the first Artemis moon lander, a vehicle based on the company’s huge privately-funded Starship rocket.

The space agency plans to select another lunar lander provider to ensure the Artemis program has at least two ships capable of transporting astronauts to and from the moon’s surface. The Orion spacecraft will link up with the lunar landers near the moon, eventually using a mini-space station called the Gateway to as a waypoint to link up with the moon ships.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.