Delayed a year by a launch failure, the coronavirus pandemic and a stretch of stiff upper level winds this summer, an Italian-made Vega rocket vaulted into orbit from French Guiana on Wednesday night and deployed 53 small satellites from 13 countries to punctuate a flawless return to flight mission.

The rideshare launch set a record for the most satellites ever flown on a European rocket, and helped validate process changes introduced to resolve the problem on the Vega’s second stage that caused a failure on the launcher’s previous mission.

The 98-foot-tall (30-meter) rocket lit its solid-fueled first stage at 9:51:10 p.m. EDT Wednesday (0151:10 GMT Thursday), immediately boosting the Vega launcher away from the European-run Guiana Space Center on the northern coast of South America with nearly 700,000 pounds of thrust.

Heading north into a clear late night sky, the Vega rocket flew downrange over the Atlantic Ocean and shed its first stage around two minutes after liftoff.

The Vega’s second and third stage Zefiro 23 and Zefiro 9 motors ignited to continue the climb into orbit, followed by four burns of the rocket’s liquid-fueled AVUM fourth stage to place the 53 payloads into two distinct polar orbits 320 miles (515 kilometers) and 329 miles (530 kilometers) above Earth, each tilted at an angle of about 97.5 degrees to the equator.

“For Europe, it’s the very first time we’ve arranged a so-called rideshare mission,” said Giulio Ranzo, CEO of Avio, the Italian company that builds most of the Vega rocket. “We’re very happy for this to open up the new market for small satellites for Europe.”

The solid-fueled Zefiro 23 second stage on Wednesday night’s mission included improvements designed to address a structural deficiency that led the destruction of a Vega rocket on its previous launch in July 2019.

The failure last year caused the rocket and its payload — Falcon Eye 1 military reconnaissance satellite for the United Arab Emirates — to crash back to Earth in the Atlantic Ocean north of French Guiana.

Avio said an independent investigation into the July 2019 launch failure concluded super-hot gas from burning solid propellant impinged on the structure of the Vega rocket’s Zefiro 23 second stage, resulting in a “thermo-structural failure” on the second stage’s forward dome.

The hot gas, which burns at more than 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (3,000 degrees Celsius), damaged or burned through the carbon fiber structure on the second stage. The structural failure led to the in-flight breakup of the launch vehicle with the UAE’s Falcon Eye 1 spy satellite.

According to Ranzo, Avio’s CEO, investigators determined a “manufacturing anomaly” slipped through Avio’s quality control checks.

“We had thermal protection (on the second stage) where the thickness was perhaps less than one millimeter short, so we had a very, very tiny deviation that was undetectable to all the quality checks,” Ranzo said in March during an interview with Spaceflight Now.

“So what we have done is we have greatly improved the technologies to allow for the manufacturing quality controls — using not only ultrasound but also digital radiography — in a much finer way with respect to work we used to do in the past,” Ranzo said.

Avio pulled hardware from the company’s Zefiro 23 production line in Italy, ran it through the improved quality control checks, and successfully test-fired the rocket motor at a test site in Sardinia.

Ranzo said Avio also added extra thermal insulation on the Zefiro 23 second stage motor.

“It’s probably not necessary, but we increased the safety margin,” he said in March. “So we are now approaching the flight with much better comfort with respect to safety.”

Engineers also modified parts of the Vega’s telemetry, flight safety and self-destruct devices, Ranzo said.

An independent investigation panel issued 20 recommendations, including 14 mandatory action items that were implemented before the return to flight mission Wednesday night.

The changes made the Vega rocket “even more robust,” said Roland Lagier, Arianespace’s chief technical officer.

The 53 spacecraft deployed by the Vega’s AVUM upper stage come from 21 customers in 13 countries, including European Space Agency member states, the United States, Canada, Argentina, Thailand and Israel.

Watch replays of tonight’s Vega launch showing rocket darting into the night sky over French Guiana with nearly 700,000 pounds of thrust.

Continuing coverage: https://t.co/9mmCmdKVgO pic.twitter.com/xkt5fEfGA7

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) September 3, 2020

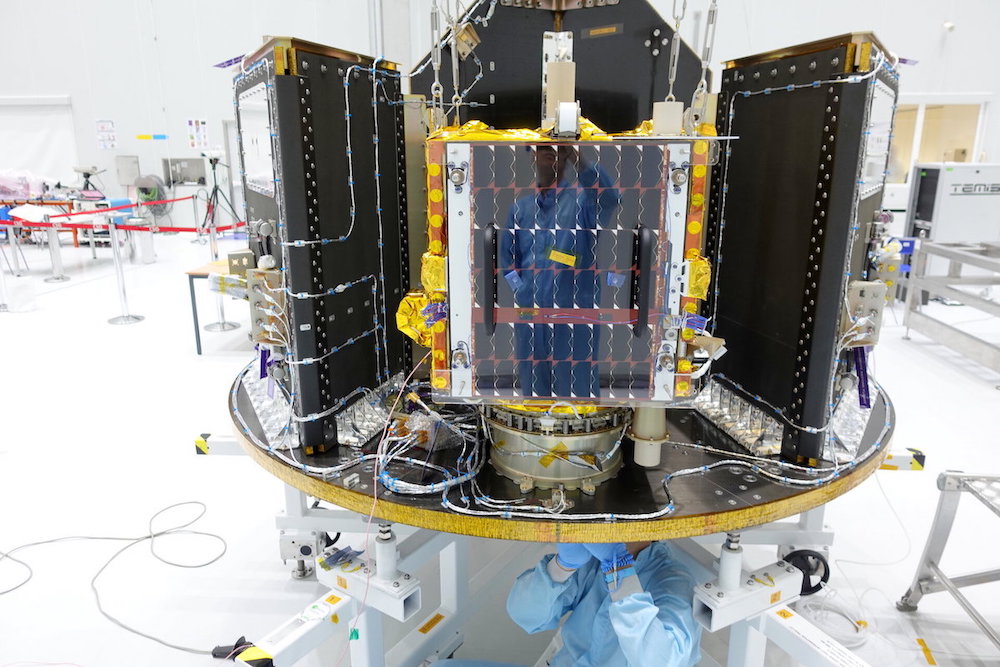

Sized to carry small-to-medium-class payloads into orbit, the Vega rocket flew with a new payload accommodation structure designed to allow dozens of satellites to launch on the same mission. The modular structure can be adapted to accommodate various numbers of small satellites of different sizes, and Arianespace and Avio plan to make it a regular part of their commercial launch service offering after Wednesday’s successful “proof of concept” demonstration flight.

The Small Space Mission Service, or SSMS, payload dispenser that flew for the first time Wednesday night was jointly funded by the European Space Agency and the European Commission. SAB Aerospace in the Czech Republic and Bercella in Italy designed and manufactured the dispenser.

Aggregating numerous small payloads on a single rocket can reduce launch costs for individual satellite operators.

“This project is a very important one because it shows flexibility, agility, and also cost reduction,” said Jan Woerner, ESA’s director general.

Arianespace declared success after the Vega rocket released its 53 payloads into orbit late Wednesday.

“With Vega’s successful return to flight, we are delighted to have served 21 customers from 13 different countries,” said Stéphane Israël, Arianespace’s CEO. “These satellites will serve a variety of different applications, including Earth observation, the battle against climate change, telecommunications, the Internet of Things, science, as well as education. With this shared launch, space becomes accessible to everyone, including research labs, universities and startups.”

The SSMS proof of concept flight was supposed to launch last September, but that schedule was impacted by the investigation into the Vega launch failure in July 2019. With the investigation and required reliability improvements complete, teams in French Guiana were in the final stages of readying the Vega rocket and its payloads for launch in late March when the coronavirus pandemic forced a suspension of launch operations at the spaceport in South America.

Work resumed in May, and engineers hoped to launch the Vega rocket in late June. But a stretch of unacceptable upper level winds kept the rocket grounded, and managers decided to stand down and recharge batteries on the launcher and its satellites after a series of scrubbed launch attempts.

The Vega rocket missed a launch slot in mid-August due to delays in the launch of a heavy-lift Ariane 5 rocket. Arianespace called off another launch attempt Tuesday night as a typhoon threatened a telemetry station in South Korea that was needed to track the Vega rocket after liftoff.

With the typhoon threat passed, Arianespace finally proceeded with the Vega’s launch Wednesday night.

The first satellite released into a 320-mile-high (515-kilometer) orbit by the Vega’s AVUM upper stage was Athena, a 304-pound (138-kilogram) spacecraft built by Maxar in California. Athena is a small experimental communications satellite for PointView Tech, a subsidiary of Facebook, that will test technologies that could be used in a future constellation of small satellites to provide global broadband Internet services.

Athena is PointView Tech’s first satellite.

A 330-pound (150-kilogram) spacecraft developed by the Italian space company D-Orbit also rode to space on the Vega rocket. D-Orbit’s ION Satellite Carrier is loaded with 12 SuperDove Earth-imaging CubeSats for Planet, which will be released after the carrier craft separates from the Vega rocket’s upper stage in orbit.

Counting the 12 SuperDoves inside the ION Satellite Carrier, the SSMS proof of concept mission is actually launching with 65 satellites.

D-Orbit plans to develop more capable CubeSat carriers for future missions with propulsion systems that could maneuver customers’ nanosatellites into different orbital slots after separation from their launch vehicle. That capability could give CubeSat operators the ability to still put their spacecraft into tailored orbits even if launching on a rideshare flight to a slightly different altitude or inclination.

The launch marked the first use of D-Orbit’s InOrbit Now, or ION, service.

The largest satellite ever built in Luxembourg also hitched a ride into orbit on the Vega launch vehicle. Named ESAIL, the 246-pound (112-kilogram) spacecraft was developed in partnership between ESA and exactEarth, a Canadian company with maritime tracking sensors on more than 60 satellites already in orbit.

ESAIL is part of an ESA initiative called SAT-AIS, managed within ESA’s telecommunication program office, which aims to foster the development of a fleet of small satellites to receive and relay Automatic Identification System signals from ships.

Built by LuxSpace, ESAIL was funded by the Luxembourg Space Agency and other ESA member states. The project also received private funding from exactEarth, which will operate the satellite on a commercial basis.

A major user of ESAIL satellite data will be the European Maritime Safety Agency. Officials say ESAIL will improve fisheries monitoring, maritime fleet management, environmental protection, and border and maritime security services.

Slovenia’s NEMO-HD Earth-imaging microsatellite was also on the Vega launch. The 143-pound (65-kilogram) NEMO-HD spacecraft will collect medium-resolution color still and high-definition video imagery that can be downlinked to the ground in realtime.

NEMO-HD was built in Canada at the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies Space Flight Laboratory for the Slovenian Center of Excellence for Space Sciences and Technologies, or SPACE-SI.

A 99-pound Spanish microsatellite named UPMSat 2 was also on the SSMS rideshare cluster. Loaded with tech demo payloads, it was developed as an educational project by students at the Polytechnic University of Madrid since 2009.

The ÑuSat 6 Earth-imaging microsatellite also launched Wednesday night. It’s the next spacecraft to join a remote sensing satellite fleet owned by Satellogic, an Argentine company.

Headquartered in Buenos Aires with a satellite manufacturing facility in Montevideo, Uruguay, Satellogic is building a fleet of satellites to cover the globe with visible, hyperspectral and infrared imagery. The company is one of several startups active in the commercial Earth-imaging market, along with Planet, BlackSky, ICEYE, and others.

Satellogic plans to deploy a fleet of 90 microsatellites primarily using Chinese rockets. ÑuSat 6 will be Satellogic’s 11th satellite to launch, and the first to fly on a European rocket.

A small satellite designed to monitor greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere was also deployed by the Vega rocket. The GHGSat-C1 satellite, with a launch mass of about 34 pounds (15.4 kilograms), is owned by a startup named GHGSat based in Montreal.

The Canadian-built spacecraft is the second to launch for GHGSat, which says the satellite will be capable of detecting methane emissions from specific sources, such as oil and gas wells. Buoyed by financial infusions from climate-focused investment funds, the oilfield services company Schlumberger, and the governments of Canada, Alberta and Quebec, GHGSat aims to field a fleet of greenhouse gas-monitoring satellites to feed data to regulators and industry.

After deploying the seven heavier payloads, the Vega rocket’s AVUM upper stage lit its liquid-fueled engine two more times to boost itself into a slightly higher orbit.

The SSMS dispenser then ejected 46 smaller nanosatellites over a period of less than three minutes.

The smaller payloads included 14 SuperDove remote sensing spacecraft for Planet, and eight Lemur-2 CubeSats for Spire’s fleet of maritime, aviation, and weather monitoring nanosatellites. The SuperDove and Lemur-2 satellites are about the size of a shoebox.

The remaining payloads deployed by the Vega rocket Wednesday night included:

- 12 tiny SpaceBEE satellites — each about the size of a slice of bread — for Swarm Technologies’ low-data-rate communications network

- FSSCat A and B, two environmental monitoring CubeSats developed by developed by ESA and the Polytechnic University of Catalonia in Barcelona, Spain

- DIDO-3, a CubeSat for the Swiss company SpacePharma

- PICASSO, developed for ESA by the Belgian Institute of Space Aeronomy to collect data on the atmosphere and ozone

- SIMBA, a Belgian CubeSat to measure how much solar energy enters Earth’s atmosphere

- TRISAT, a CubeSat developed by the University of Maribor in Slovenia

- AMICalSat, a CubeSat jointly developed by the Grenoble University Space Center in France and Moscow State University in Russia

- NAPA 1, a CubeSat that will be Thailand’s first military satellite

- Kepler Communications’ TARS tech demo CubeSat

- OSM-1 CICERO, the first satellite manufactured in Monaco

- Tyvak 0171, a CubeSat built by Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems of California for an undisclosed customer

With the Vega rocket back in service, Arianespace’s next mission is scheduled for launch Oct. 16 from the spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. A medium-lift Russian Soyuz rocket is being prepared to loft the Falcon Eye 2 military spy satellite for the United Arab Emirates.

Built by Airbus, Falcon Eye 2 is a twin to the Falcon Eye 1 surveillance craft destroyed during the Vega launch failure last year.

The next Vega rocket is scheduled to launch in November the Spanish SEOSat-Ingenio Earth observation satellite and the French Taranis scientific research satellite.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.