Virgin Orbit is setting modest expectations ahead of the company’s first attempt to reach orbit with a liquid-fueled air-launched rocket, emphasizing a hunger for flight data on the test launch, which could occur as soon as Monday off the coast of Southern California.

The company called off a launch attempt Sunday to address what officials characterized as a “minor sensor issue” discovered during final pre-flight preparations. Later Sunday, Virgin Orbit said its team had resolved the sensor issue and confirmed it planned to stage another launch attempt Monday during a window between 1 p.m. and 5 p.m. EDT (10:00 a.m.-2:00 p.m. PDT; 1700-2100 GMT).

Virgin Orbit says it is not providing a public live video feed of the launch, and the location of the release point some 100 miles (160 kilometers) west-southwest of Long Beach, California, provides little opportunity for people to see the rocket fire into space.

Positioned under the left wing of a Boeing 747 carrier jet, the two-stage, 70-foot-long (21-meter) LauncherOne rocket is designed to place small payloads of up to 660 pounds (300 kilograms) into a polar sun-synchronous orbit more than 300 miles (500 kilometers) above Earth.

The Boeing 747 carrier aircraft, named “Cosmic Girl,” will take off from Mojave Air and Space Port in California around 45 minutes to an hour before launch time, then fly out to a location west of the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California.

Four people will be aboard the airplane, including a two-person flight crew and two launch engineers.

Once lined up on a south-southeasterly heading, the jumbo jet’s flight crew will pitch the airplane up at an angle of more than 25 degrees, then command release of the 30-ton rocket at an altitude of about 35,000 feet (nearly 10,700 meters).

A few seconds later, the rocket will ignite its kerosene-fueled NewtonThree main engine and begin the climb into space.

If the flight goes according to plan, Virgin Orbit’s rocket will be the first liquid-fueled satellite launcher to fire into orbit from an airborne platform. Northrop Grumman’s Pegasus rocket, which burns pre-packed solid propellants, became the first air-launched rocket to reach orbit in 1990.

Dan Hart, Virgin Orbit’s president and CEO, said Saturday the company’s goal is to gather as much data as possible on the first LauncherOne mission.

“This is a test flight, so the purpose of this flight is to incrementally test the rocket and the airplane and the system as we pass through the operations,” Hart said. “So we’ll be getting data on our (propellant) load sequence, our captive carry flight out, and the full flight of the rocket after it drops through first stage flight, separation, second stage flight, and so forth.

“And we have telemetry stations around the world to capture the data as it comes down,” Hart said. “The data … is the product of that flight, and every increment that we learn, from the moment that we start fueling the rocket, to flying it out, to lighting the engines, and observing the response of the system … is a huge step in the maturation of a system.”

Engineers have performed numerous engine test-firings, stage and fairing separation tests, and propellant loading rehearsals. Virgin Orbit also last year released an inert LauncherOne rocket over a military test range at Edwards Air Force Base in California, verifying the airplane’s release mechanism.

Hart said the data gathered on the first launch will anchor engineering models that have, so far, only relied on testing performed on the ground or in the atmosphere.

Will Pomerantz, Virgin Orbit’s vice president of special projects, said Saturday that the first LauncherOne mission will have “a number of firsts.”

“History is not terribly kind to maiden flights,” he said. “I’m a big nerd, so i have a spreadsheet of every launch that’s ever happened. Taking my best faith estimate, it’s about half of maiden (rocket) flights fail. So that’s sort of the historical odds we’re against.

“This will be the first time that we’ve lit our NewtonThree booster stage engine in flight,” Pomerantz said. “It’s coming after a lot of testing, but this is kind of the next big step. That moment of ignition of the NewtonThree, I would say, is the key moment in this flight. We’ll keep going as long as we can after that, potentially even all the way to orbit, but we’re really excited about the data, and about the moment of ignition, and as far as we can get after that.”

Both stages of the LauncherOne vehicle consume kerosene and cryogenic liquid oxygen propellants. The NewtonThree engine produces around 73,500 pounds of thrust at full power.

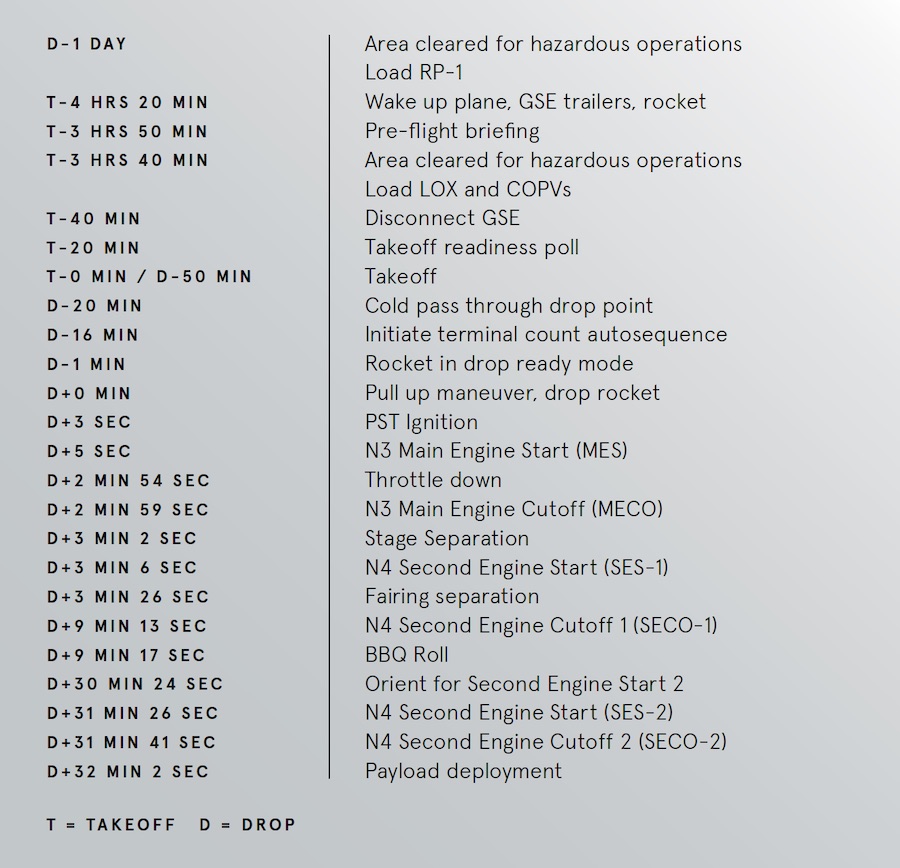

Assuming the rocket performs as designed, the LauncherOne’s first stage will shut down and separate around three minutes into the flight. Then the second stage’s NewtonFour engine will ignite at T+plus 3 minutes, 6 seconds, followed by jettison of the rocket’s payload shroud around 20 seconds later.

The NewtonFour engine will shut down around nine minutes into the mission, then the rocket will coast through space around 21 minutes before reigniting the second stage engine for around 15 seconds. An inert payload carried on this first LauncherOne mission will then deploy at about T+plus 32 minutes, 2 seconds.

Meanwhile, the Cosmic Girl carrier aircraft will return to Mojave for landing around 30 minutes after releasing the rocket.

Virgin Orbit said it is targeting a low-altitude orbit for the test flight to avoid leaving any debris in space for an extended period of time.

The debut test flight caps years of development of the small satellite launch system. The effort began as a project of sister company Virgin Galactic, which focuses on the suborbital space tourism market.

Both companies are part of Richard Branson’s Virgin Group.

Virgin Galactic says it first studied the LauncherOne concept in 2007, and development began in earnest in 2012. Engineers in 2015 scrapped initial plans to drop the rocket from Virgin Galactic’s WhiteKnightTwo carrier aircraft, and kicked off development of a redesigned system using a 747 jumbo jet taken from Virgin Atlantic’s commercial airline fleet.

Headquartered in Long Beach, California, Virgin Orbit was established in 2017 as a spinoff of Virgin Galactic. The company currently has around 500 full-time employees, according to Pomerantz.

Hart said the company will wait until weather conditions are favorable and all systems are in top-notch form before proceeding with the test launch.

“We want everything to be absolutely right as we go for this first launch,” said Hart, a former engineer and executive at Boeing, where he managed the company’s work on government space programs, including GPS navigation satellites, the military’s Wideband Global SATCOM communications network, the X-37B spaceplane, and NASA’s TDRS data relay satellites.

“As far as the go/no go criteria, there are several gates as we go through the operation,” Hart said. “We’ll have a gate before we take off from Mojave. There are gates before that as we’re loading (propellant). Are we ready to disconnect the rocket and taxi off? Once we get to altitude, we’ll have our flight crew monitoring, as well as our ground crew.

“If we were to have any communication interrupts, the flight crew is autonomous, and they can carry on the mission on their own,” he said. “There is a gate before terminal count, as you would imagine, and we’ll be going through launch commit criteria, as is pretty standard with rockets.

“The way you approach a milestone like this is through a number of gates and a lot of discussion,” Hart said. “And you essentially get to a point where you have looked under every rock and verified that there’s nothing more for you to do to verify that the system is ready, and that’s what we have done.”

Hart said Virgin Orbit has a backlog of business valued in the “hundreds of millions of dollars,” including launch contracts with the U.S. military, NASA and commercial customers.

“There is a transformation going on in space right now, where the technology (has) enabled small satellites, much smaller than traditionally available, to do real work in space, typically to do that work from low Earth orbit,” Hart said.

Other companies are vying for the same slice of the launch market.

Rocket Lab, a U.S.-New Zealand company, debuted its Electron small satellite launcher in 2017. Another U.S. launch company, Firefly Aerospace, aims to fly its small new Alpha rocket into orbit before the end of this year.

And there are opportunities for small satellites to launch as rideshare payloads on bigger rockets. SpaceX says it charges as little as $1 million to launch a piggyback payload of up to 440 pounds, or 200 kilograms, with a primary payload on a Falcon 9 rocket.

Hart said Virgin Orbit has initially set a launch price of about $12 million per LauncherOne flight, but that could be divided among multiple customers if their satellites are light enough.

Fielding an airborne launch system has its benefits, according to Virgin Orbit.

“We’re differentiated in our air launch capability, which gives us much much higher flexibility, and in fact even mobility, which has never been a capability in launch, with very little exception,” Hart said. “Our purpose is to be able to be responsive and to get payloads to the right orbit that meet business plans, and do it when they need to.”

Satellite operators with rideshare payloads riding into space with a larger spacecraft have to make tradeoffs, Hart said. Their satellites won’t be able to launch until the primary satellite is ready to go, and rideshares often launch into orbits that aren’t ideal for their mission.

Virgin Orbit also plans to launch from different locations around the world. Future launches are scheduled to be staged out of Guam, and the company is looking at basing missions from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the United Kingdom and Japan.

The first air-launched satellite booster — Northrop Grumman’s Pegasus — has amassed 44 flights since 1990. But it has not been viable in the commercial launch market, and instead has relied on U.S. government business to remain operational.

The most recent Pegasus launch contract awarded by NASA cost more than $56 million, more than four times Virgin Orbit’s quote for a satellite launch.

“We are a liquid rocket, and we chose liquid because it allows us to be very efficient in our manufacturing and our build operations,” Hart said.

“When you’re carrying essentially ICBM stages around a factory, you can imagine the care and the extra regulations and processes that you have to put in place to do so,” said Hart, referring to the Pegasus rocket’s solid-fueled rocket motors. “That’s not us. We build our rocket from state-of-the-art composite technology, so we can build our tanks very quickly. They’re very light. We can move them around the factory efficiently, and we don’t need bells and whistles and an army of people standing around making sure that nothing goes wrong when we move a fuel tank from one side of the factory to the other.

“We’re very vertically integrated in that we build almost everything on the rocket, so the composite shells that make up the tanks, the engines, we build in our factory,” he said.

He also said the 747 carrier aircraft is easier to operate than the L-1011 used by Northrop Grumman for the Pegasus program. Northrop Grumman’s L-1011 is the last airplane of its type still flying in the United States.

“Our system is coming to life at a time when technology has provided for small satellites that can do tremendous real work in space,” Hart said. “This time, now in 2020, is a renaissance for small satellites. You can see that with so many companies who are building satellites. Companies, countries, industries who never would have thought of having or owning a constellation are bringing that forward, and that was not true 30 years ago.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.