EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated with confirmation of acquisition of signal from all 34 satellites.

BAIKONUR COSMODROME, Kazakhstan — A Russian Soyuz launcher fired into orbit from the remote steppe of Kazakhstan Thursday with 34 satellites built on Florida’s Space Coast, commencing a sequence of launches to deploy a network of nearly 650 spacecraft for a global broadband network owned by OneWeb.

The launch Thursday was the first of up to 10 OneWeb missions this year, each carrying from 32 to 36 OneWeb satellites into orbit from spaceports in Kazakhstan, Russia and French Guiana. By next year, when OneWeb aims to have at least 648 satellites in orbit, the company plans to begin providing global Internet service.

Limited service could begin before the end of this year, according to OneWeb.

The 15-story Soyuz-2.1b rocket climbed away from the Site 31 launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome at 2142:41 GMT (4:42:41 p.m. EST) Thursday and shot through an overcast cloud layer in the predawn skies over Kazakhstan, where liftoff occurred at 2:42 a.m. local time Friday.

Kerosene-fueled engines generated more than 900,000 pounds of thrust to power the Soyuz launcher off the launch pad. Within two minutes, four liquid-fueled first stage boosters shut down and jettisoned, and the Soyuz core stage switched off and separated nearly five minutes after liftoff.

Moments after the third stage engine ignited, the Soyuz shed its clamshell-like aerodynamic payload shroud. The third stage deployed a Fregat upper stage on a preliminary suborbital trajectory more nine minutes into the mission, completing the role of the Soyuz rocket for the mission.

The main engine of the Fregat upper stage ignited two times to place the 34 OneWeb satellites into a targeted polar orbit roughly 280 miles (450 kilometers) above Earth, with an inclination of 87.4 degrees to the equator.

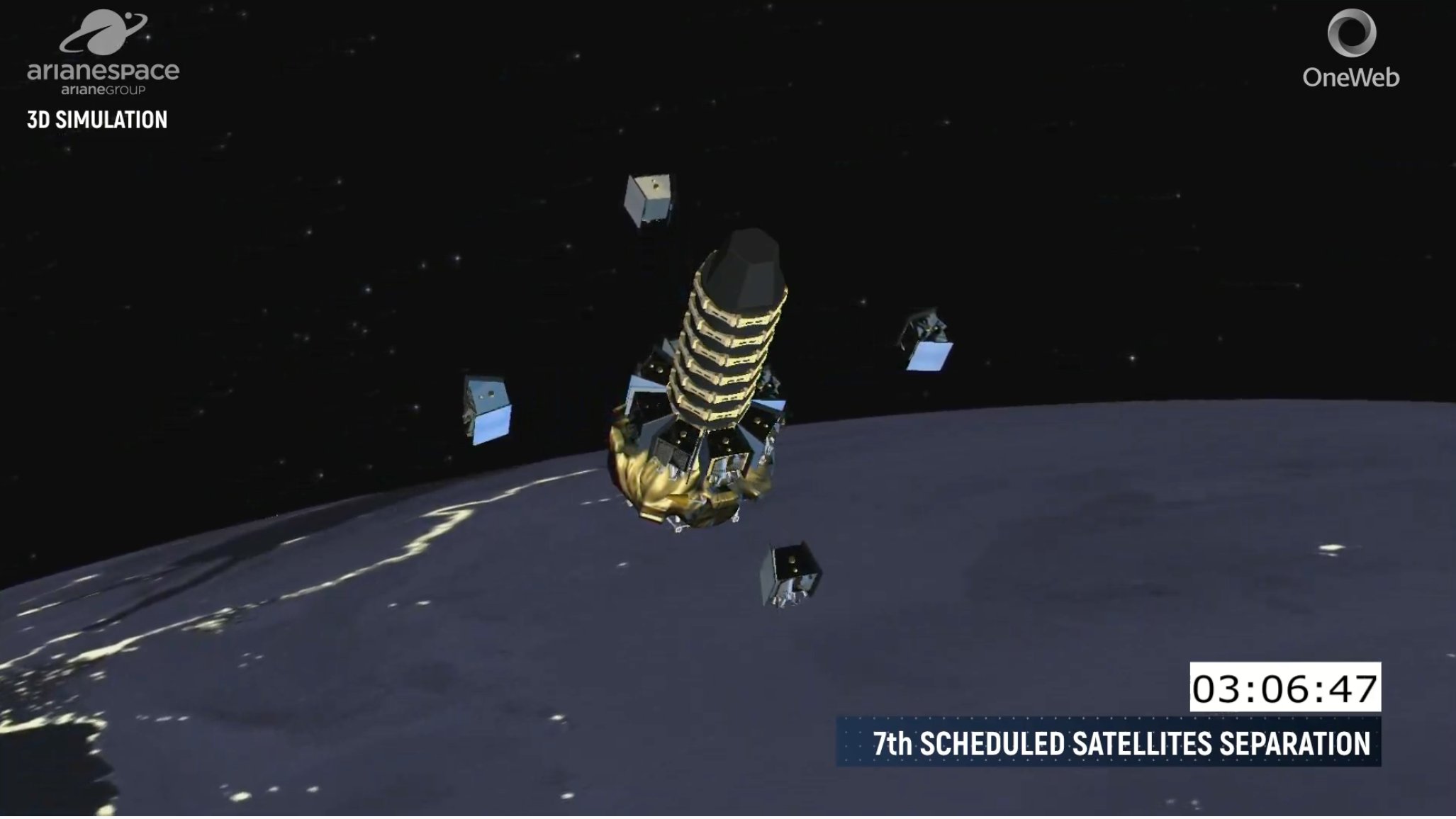

Then began a series of deployments to release the 34 OneWeb satellites from a composite dispenser, or connecting interface, made by RUAG Space in Sweden.

First, two of the 325-pound (147.5-kilogram) satellites separated from the top of the cluster. The remaining 32 spacecraft separated in groups of four at intervals of approximately 20 minutes, with maneuvers by the Fregat’s smaller attitude control thrusters in between to ensure the satellites did not collide.

The satellite separation events largely occurred when the Fregat was outside the range of ground tracking stations. Officials from OneWeb and Arianespace — which arranged Thursday’s launch under contract to OneWeb — updated the status of the deployment sequence as they received data from the Fregat upper stage.

The last group of OneWeb satellites flew off the Fregat’s dispenser around 3 hours, 45 minutes into the mission. About an hour later, officials received telemetry data confirming the deployment of all 34 satellites.

Later Friday, ground teams at OneWeb’s satellite operations center received signals from all 34 satellites after several passes over ground stations.

The spacecraft were manufactured on assembly lines at a new factory operated by OneWeb Satellites, a joint venture between OneWeb and Airbus Defense and Space, near the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

“This is a very significant launch for us, and I think this launch and really the next launch are critical because it will show the success that we’ve had with OneWeb Satellites, the joint venture between us and Airbus, and getting the assembly line approach actually working,” said Adrian Steckel, CEO of London-based OneWeb. “I think the 34 satellites that are on this one are a demonstration that after many months of work, we can get up to that rate.”

“The real proof will be when we have 34 satellites for Launch No. 3 ready by Feb. 17 or so and shipping out to Baikonur. We’re very happy about that,” Steckel said.

The OneWeb satellites, each designed for a minimum of five years of commercial operations, will extend their power-generating solar panels and activate their xenon plasma propulsion systems to begin post-launch checkouts. Each satellite will use its xenon thruster to reach an operational orbit at an altitude of 745 miles (1,200 kilometers) in about five months, where the OneWeb network will spread an initial block of 648 satellites among multiple orbital planes.

OneWeb scaled back the size of its first-generation satellite network in 2018 after finding that the first spacecraft built for the constellation performed better than expected.

But OneWeb has ambitions to grow its broadband fleet to 1,980 satellites to meet higher demand.

Founded by Greg Wyler, a satellite and telecom entrepreneur, OneWeb announced last year that it demonstrated live HD video streaming through the company’s first six satellites launched in February 2019. OneWeb and Iridium, which operates a low Earth orbit network with 66 cross-linked L-band communications and data relay satellites, announced an agreement in September to work toward a combined service offering.

OneWeb is in heated competition in the low-latency satellite broadband market with SpaceX, which has launched 240 Starlink Internet satellites on four dedicated Falcon 9 rocket flights since last May. More than 20 additional Falcon 9 launches — each with around 60 Starlink payloads — could take off before the end of 2020, aside from SpaceX’s launches for other customers.

SpaceX, which builds its satellites in Redmond, Washington, plans to initially launch up to 1,600 satellites on a series of Falcon 9 rockets to fly in 341-mile-high (550-kilometer) orbits. The company, led by billionaire Elon Musk, has approval from the Federal Communications Commission to eventually operate up to 12,000 Starlink broadband satellites.

Documents filed with the International Telecommunication Union last year suggested SpaceX could seek regulatory authority for up to 30,000 additional spacecraft, bringing the Starlink network to some 42,000 satellites.

“Our satellites are at 1,200 kilometers, there’s are at 550,” Steckel said in a pre-launch media briefing in Kazakhstan. “That’s just geometry. Our satellites have a bigger field-of-view. Their system doesn’t give them global coverage, even though they have a lot more satellites, because they’re lower and they do not have inter-satellite links (yet).

“And because ours are higher and we have big ground stations, we’re able to sort of reach over the horizon and guarantee that coverage of the oceans and have global coverage,” Steckel said. “We have (regulatory) filings for thousands of satellites… and they have for tens of thousands of satellites.”

Like OneWeb, SpaceX says it could start serving high-latitude regions the Starlink broadband coverage this year, followed by the inauguration of global service.

SpaceX can launch Starlink satellites on the company’s own Falcon 9 rockets, and the company is using the Starlink program to fill its launch manifest as other sectors of the satellite industry have experienced a downturn.

OneWeb has taken a more traditional satellite development approach with an international supply chain. Gingiss said about half of the parts on each spacecraft come from North America, and the other half come from Europe.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is also investing in the planned Kuiper broadband network that could also number thousands of satellites.

While Starlink and Kuiper are primarily backed by billionaires, OneWeb’s investors include the Japanese company SoftBank, Airbus, Qualcomm and Grupo Salinas. Richard Branson’s Virgin Group is also a OneWeb financial backer.

OneWeb said last March that it had raised $3.4 billion to date to pay for the construction of the network, which is scheduled to begin providing Internet service over the Arctic before the end of 2020, thanks to ground stations already operational in Alaska and Norway.

OneWeb Satellites is producing more than 600 additional satellites for OneWeb on two assembly lines at the company’s Florida factory.

“These are the first built at our high-capacity assembly lines in Florida,” said Tony Gingiss, CEO of OneWeb Satellites. “We’ve been ramping that factory up over the last six to nine months.”

“We’re already midway through the second batch to deliver at the middle of this month, and that is really demonstrating that we can hit roughly 34 satellites a month to deliver to keep the launch cadence that OneWeb wants,” Gingiss said.

Steckel said that there’s room in the global commercial market for both SpaceX and OneWeb because the companies are taking different approaches to their low-latency broadband networks.

“We’re going to be competitive,” Steckel said. “We have a different approach. We’re going to get landing rights (and market access) in places that Starlink won’t. We think there’s 40 percent of the land mass in the world where they won’t and we will. That has to do with our architecture. It also has to do with our approach to doing business. It also has to do with our flag. We’re a UK company. That gives us the ability to try to build a bridge … We have shareholders and support from institutions all around the world.

“We’re also attacking a different part of the marketplace,” he continued. “We’re not going to try to compete against the Comcasts or the Oranges of the world. Over time, what you’ll find is our technologies and their technologies are pretty much the same thing. But the fact that you’re using the same technology doesn’t mean you’re executing the same business model. It’s the difference between being a consumer play or an enterprise play.”

According to Steckel, OneWeb’s network will be more attractive to countries like China and Russia. He said OneWeb’s satellites will relay broadband signals through powerful ground stations, or gateways. The company intends to develop or use around 40 to 45 gateways distributed around the globe.

OneWeb and the government of Kazakhstan have announced plans to put a gateway in Kazakhstan to create a broadband data hub for Central Asia. Steckel said that partnership could be a model for OneWeb’s entry into other markets.

“I don’t believe that sitting back in our office, me and our team will be able to properly manage a global system, and know what does the client want in Madagascar, versus South Africa, versus Brazil, versus Wales, Scotland, or Switzerland,” Steckel said. “You need people locally to implement, and to design the products and sell the product. That goes with the notion of having partners with aligned economics and aligned interests.”

SpaceX’s Starlink network will eventually use laser data links between satellites, enabling the network to route signals around the world without going through ground stations.

“SpaceX has gone out of their way to emphasize that they were going to have inter-satellite links, and that they will have inter-satellite links,” Steckel said. “That is fundamental to the structure of their system, and that is not something that’s acceptable to governments who want to make sure that they have the ability to exercise sovereignty over the Internet.”

“It’s a different business plan,” he said. “Nothing in what I’m saying is a criticism of them. They could be highly successful. We’re playing a different ball game, but we’re both using similar technology.”

Large constellations of satellites like those being deployed by OneWeb and SpaceX have raised concerns about space junk and their interference with ground-based astronomy.

Every OneWeb satellite, including those launched Thursday, has a grapple fixture to allow other spacecraft link up in orbit and bring them back into Earth’s atmosphere to burn up on re-entry.

But that measure would only be used in a worst-case scenario. OneWeb plans to deorbit its satellites after their useful lives are over, using the spacecraft’s plasma propulsion system to lower altitude and re-enter the atmosphere.

SpaceX’s Starlink satellites are brighter than designers predicted, and they are particularly visible soon after each launch, when the spacecraft are at lower altitudes and relatively close together.

SpaceX launched a Starlink satellite with an experimental dark coating in January to see if the change makes the craft less reflective of sunlight. But results from the experiment will not be known until the satellites reaches its operational orbit in the coming weeks.

“We’re going to do the most we can to mitigate (astronomers’ concerns),” Steckel said. “We’re not visible to the naked eye. We are visible to telescopes. It’s hard to get around some of those facts.”

Scientists have also questioned whether constellations of thousands of satellites broadcasting broadband data will interfere with radio astronomy, which uses giant antennas to listen to faint radio signals generated from distant stars and galaxies.

“With respect to radio frequency … we’ll try,” he said. “We’re going to do the most we can. I don’t know if there will be a solution that will make everybody happy. At least we’re in dialog, and we’re trying to get feedback on what can we do.”

OneWeb’s next launch is scheduled for around March 18 on another Soyuz rocket, assuming the factory team in Florida remains on track in assembling and testing the 34 satellites for shipment to Baikonur later this month.

Soyuz launches with more OneWeb satellites later this spring and summer will originate from the Vostochny Cosmodrome in far eastern Russia, near the border with China. There are also more launches for OneWeb planned from the European-run spaceport in French Guiana.

OneWeb inked a launch contract in 2015 for 21 launches with Arianespace, the French launch services provider which oversees commercial Soyuz missions. Arianespace’s subsidiary, Starsem, arranges preparations for the Soyuz missions launching from Baikonur and Vostochny, while Arianespace itself manages Soyuz launches from French Guiana.

Steckel said OneWeb needs around 16 more launches to fill out the company’s network of 588 operational satellites. The company may eventually add at least 60 more spares to get to 648 total spacecraft in the first-generation OneWeb fleet.

“The real important number is 588, which are the operational satellites,” Steckel said. “The 648 number includes 60 spares, and we’re thinking about maybe reducing the number of spares we have up there.”

Fifteen of the additional OneWeb launches will use Soyuz rockets later this year and next year from Baikonur, Vostochny and French Guiana. And OneWeb has agreed to launch at least 30 satellites on the inaugural flight of the next-generation European Ariane 6 rocket from French Guiana at the end of 2020.

Nine more OneWeb launches are scheduled this year.

“This launch … opens a series of up to nine other launches in 2020 for the benefit of OneWeb,” Israel said. “We will have up to six launches from Baikonur and Vostochny, two (Soyuz) from French Guiana … and the Ariane 62 maiden flight by the end of the year.”

Steckel acknowledged that SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, which fly on Falcon 9 rockets with reused first stage boosters, have a lower launch cost than OneWeb.

“Of course, they have a launch cost that is far below mine,” Steckel said.

OneWeb has a contract for four launches on Virgin Orbit’s air-dropped LauncherOne rocket, each with two satellites. But those missions are tailored for adding replacement satellites to the fleet, or filling a gap in the network, not for getting a lot of satellites into orbit quickly.

Steckel said OneWeb is studying plans for a second-generation network, which could bring the constellation to near 2,000 satellites. He said finding a launch provider with an acceptable launch cost will be a big factor in deciding what rockets would send the upgraded satellites into orbit.

“We have conversations with other launch providers,” Steckel said. “We’re obviously already thinking about the next generation, what it looks like as a system, and what the cost of that is, and launch costs will be a big part of it.”

“What I can say is launch costs have come down significantly, and we think that the price per kilogram is coming down,” he said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.