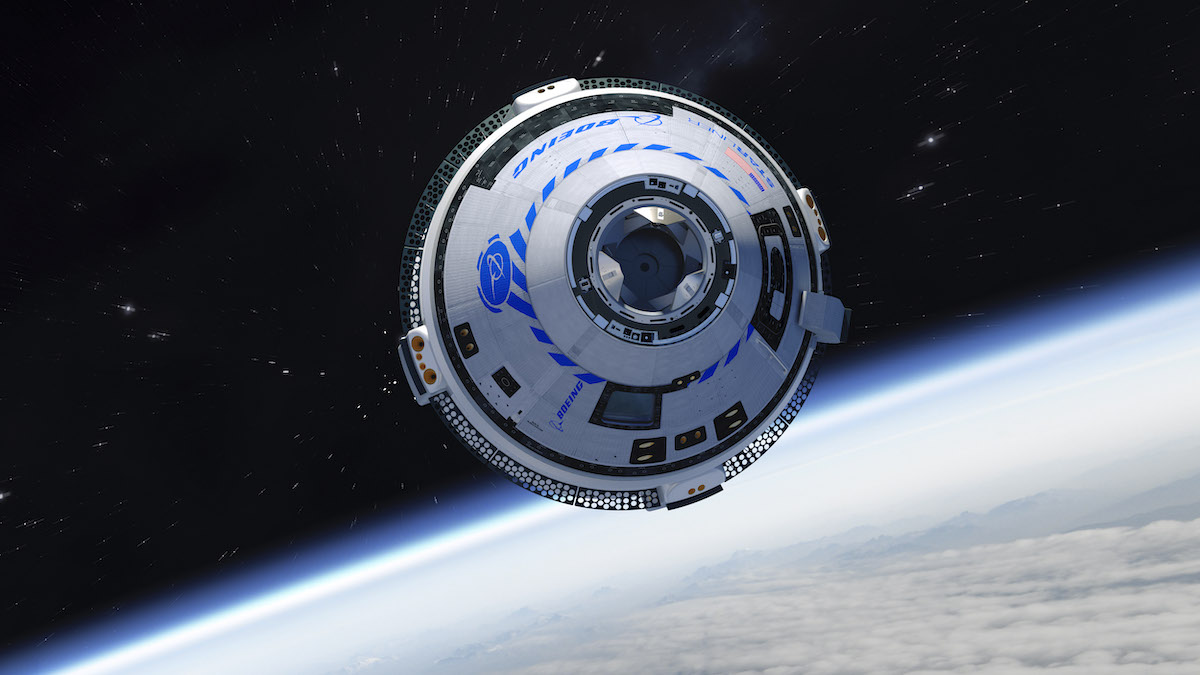

A day after a timing error caused it to enter the wrong orbit and miss its objective of meeting up with the International Space Station, Boeing’s unpiloted Starliner crew capsule prepared for its next major test Sunday, when it will plunge back into the atmosphere and target a predawn landing at White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico.

The commercial crew capsule, flying on its first space mission, is scheduled to land under parachutes in a remote corner of the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in southern New Mexico at 7:57 a.m. EST (5:57 a.m. MST; 1257 GMT) Sunday.

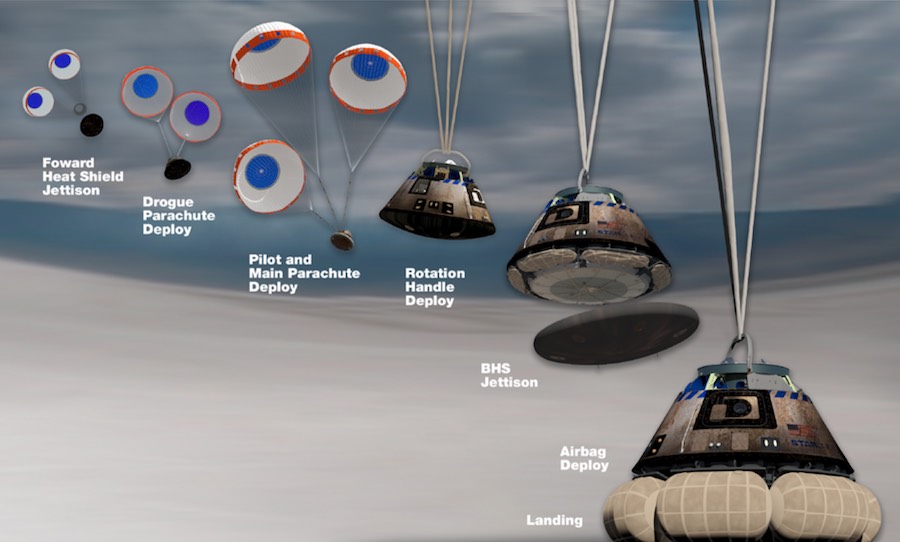

Approaching from the southwest, the 15-foot-wide (nearly 4.6-meter) spacecraft will deploy three main parachutes, jettison its head shield and inflate airbags to cushion its landing in the New Mexican desert.

A backup landing opportunity is available at White Sands at 3:48 p.m. EST (1:48 p.m. MST; 2048 GMT) Sunday.

The Starliner’s return to Earth Sunday will cut short a planned eight-day mission that was to dock with the space station. But a mission elapsed timer on the capsule errantly led the spaceship to believe it was in a different phase of its mission the moment it separated from its launcher following an otherwise successful ascent from Cape Canaveral early Friday.

The error caused the spacecraft to burn too much propellant to reach the space station, and ground teams had to manually send commands for the ship to boost itself into a safe, but unplanned orbit. Mission was only able to uplink the command after a brief communications outage with NASA’s TDRS tracking and data relay satellite network, a compounding problem officials said was likely caused by the Starliner being in the wrong orientation due to the timing problem.

Jim Chilton, senior vice president of Boeing’s space and launch division, said Saturday that a preliminary investigation has traced origin of the timing glitch to an error before the Starliner even lifted off Friday from Cape Canaveral atop its United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

“Our spacecraft needs to reach down into the Atlas 5 and figure out what time it is, where the Atlas 5 is in its mission profile, and then we set the clock based on that,” he said. “Somehow we reached in there and grabbed the wrong (number). This doesn’t look like an Atlas problem. This looks like we reached in and grabbed the wrong coefficient.”

“As a result of starting the clock at the wrong time, the spacecraft upon reaching space, she thought she was later in the mission, and, being autonomous, started to behave that way,” Chilton said. “And so it wasn’t in the orbit we expected without the burn and it wasn’t in the attitude expected and was, in fact, adjusting that attitude.”

Boeing has released this video recorded by a forward-facing camera on the Centaur upper stage of United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 rocket, showing the Starliner capsule separating and firing thrusters soon after liftoff Friday. https://t.co/ndulUVMR02 pic.twitter.com/iQeqgAD4Wm

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) December 22, 2019

The frenetic thruster firings began almost as soon as the Starliner separated from the Atlas 5 rocket’s Centaur upper stage, which intentionally flew on a flattened, suborbital trajectory designed to reduce g-force loads on astronaut crews during a launch abort scenario.

The continuous burns caused the thrusters to get hot, and in one case, a set of thrusters depleted its propellant supply. Mission controllers say that is no problem for Sunday’s re-entry, and ground teams could route propellant from a separate thruster manifold.

“The mission elapsed timing error did absolutely result in a number of follow-on challenges,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. The spacecraft thought it was in a position it was not in, so it was trying to get in the right position. So the engines were firing, the reaction control was trying to put the spacecraft in the right position.

“And that resulted in some fo these engines exceeding their limitations, both from a temperature perspective and from a duty cycle (perspective),” Bridenstine said. “The engines are only supposed to run a certain number of times in a certain amount of time, and those were exceeded. Had the mission elapsed timing been correct, none of that would have happened.”

Chilton said that the Starliner control team are trying to put the spacecraft through as many tests as possible without flying to the space station, collecting data to help clear future Starliner missions to carry astronauts. For example, he said the spacecraft extended its docking mechanism Saturday to check the mechanical system that will link future Starliner vehicles with the space station.

The ship’s stellar navigation cameras have also been checked out in orbit for the first time, and the solar panel power generation system is working better than expected. The temperature and other parameters inside the Starliner’s pressurized cabin also look OK, officials said.

But some of the Starliner’s planned maneuvers around the space station, culminating in an autonomous docking, will remain unproven after the spacecraft’s first Orbital Flight Test.

“Not all objectives are created equal,” Chilton said. “The launch and entry, descent and landing are really big safety issues. So we’ve got the first of the big ones (done), and we’ve got a great proportion of the objectives for in-space (testing).”

One big demonstration remains Sunday with the Starliner’s re-entry and landing at White Sands.

“The entry, descent and landing is not for the faint of heart, and this vehicle has not entered,” Chilton told reporters Saturday. “We have not gone from space into the atmosphere. We have tested all the functions that you need once you get into the atmosphere during our pad abort test, but make no mistake, we still have something to prove here on entry tomorrow. We think our team has done a fantastic job being ready for that.”

Unlike previous U.S. crew capsules that splash down in the ocean, the Starliner will return to a landing on solid ground.

While the Starliner will not complete its mission to dock with the space station, Boeing and NASA officials Saturday said that some of the capsule’s rendezvous and navigation sensors were going through limited checkouts.

“Not every test objective is weighted equally,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, echoing Chilton’s earlier comments. “They’re not all the same. Launch, of course, is a big one, and entry, descent and landing is another really big one. So tomorrow is a big day. We have to be on our ‘A’ game.”

NASA and Boeing mission controllers at the Johnson Space Center in Houston are readying the spacecraft for its return.

“Now we’re going to embark on a really tough and challenging phase, executing the deorbit burn, having the service module do its disposal burn entering into the water, and then having the crew module execute the entry, fire its thrusters, and then going through the parachute deploy sequence, and then landing at the White Sands Space Harbor,” said Steve Stich, deputy manager of NASA’s commercial crew program and a former space shuttle flight director, described the Starliner’s re-entry and landing as a “tough and challenging” phase of the mission.

“It’s a system that we have to test,” Stich said. “The only way to test it will be to do an entry.”

Flying tail first in its 155-mile-high (250-kilometer) orbit, the Starliner will ignite its engines at 7:23 a.m. EST (5:23 a.m. MST; 1223 GMT) to slow its velocity by about 335 mph (150 meters per second), enough for Earth’s gravity to pull the the ship’s orbit into the atmosphere.

The braking burn will last around 50 seconds, followed moments later by the jettison of the Starliner’s service module, a disposable unit housing the ship’s abort engines, solar panels, radiators and other equipment.

The service module will burn up during re-entry over the Pacific Ocean, while the Starliner crew module — containing an instrumented test dummy nicknamed “Rosie” — will orient itself using 12 control thrusters to point its blunt end forward to face a flow of super-heated air as it plunges into the atmosphere.

Traveling at 25 times the speed of sound, the Starliner will encounter the first discernible traces of the atmosphere at 7:41 a.m. EST (5:41 a.m. MST; 1241 GMT). Temperatures outside the capsule will reach as hot as 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,650 degrees Celsius).

An ablative base heat shield, ceramic tiles and thermal blankets will protect the capsule as it heads for White Sands.

The human-rated spaceship will fly over Mexico, passing just west of El Paso before triggering its parachute deployment sequence at an altitude of around 30,000 feet (9 kilometers).

The Starliner will jettison its upper heat shield and deploy a pair of drogue parachutes. Then mortars will fire and pilot chutes will pull three main parachutes from their bags at 7:53 a.m. EST (5:53 a.m. MST; 1253 GMT). Less than a minute later, the capsule will release its bottom heat shield, allowing airbags to inflate at around 3,000 feet (900 meters).

Touchdown is scheduled for 7:57 a.m. EST (5:57 a.m. MST; 1257 GMT), more than an hour before sunrise at White Sands Space Harbor.

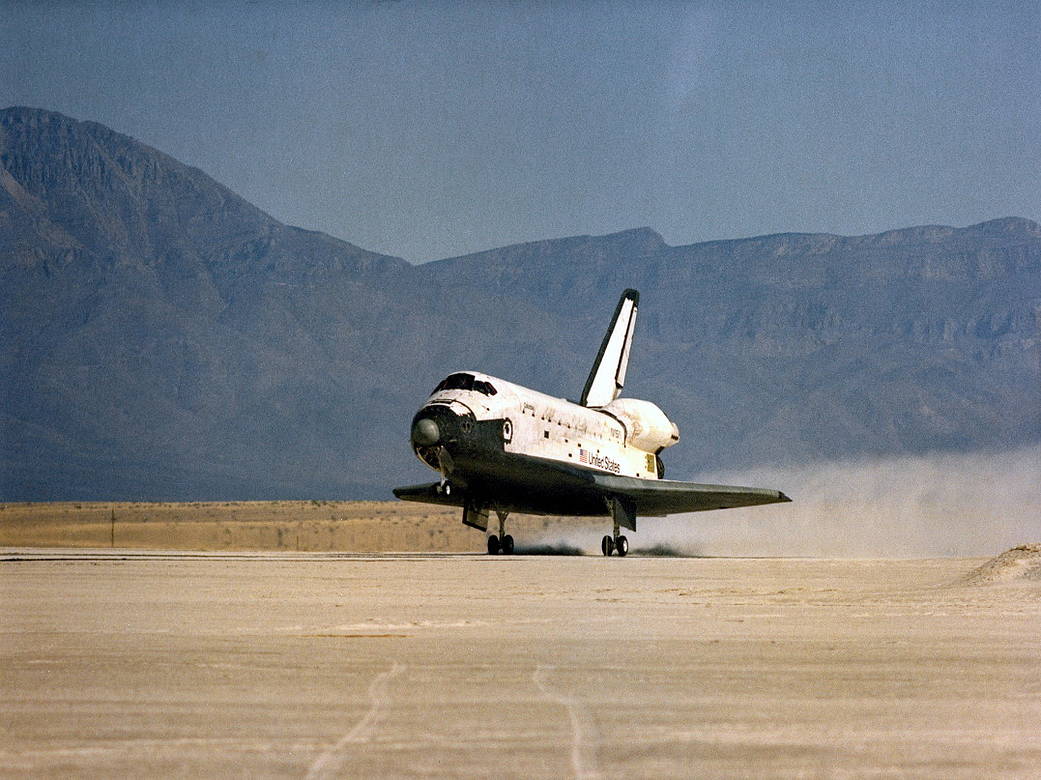

The Starliner’s landing Sunday will the second time an orbiting crew-capable space vehicle has returned to Earth at White Sands. The shuttle Columbia returned to Earth and touched down on an unpaved landing strip at White Sands Space Harbor in March 1982 to conclude NASA’s third space shuttle mission.

Boeing’s recovery team was dispatched to White Sands early to prepare for the Starliner’s landing.

“We’ll stay away from the vehicle, approximately 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) away from the intended center point of the landing,” said Louis Atchison, Boeing’s Starliner launch and recovery chief. “Upon vehicle landing, my team will go across the desert, which has its own challenges in and of itself, and we’ll approach the vehicle. We’ll make sure that the vehicle is safe for folks to go near. We do have propulsion systems on the crew module and we want to make sure that we’re in a good configuration to go open the hatch.”

On a piloted mission, the recovery team will help astronauts out of the capsule.

“For Orbital Flight Test, obviously you won’t have a crew there, but we’ll be exercising the same pieces of that activity that we would from a crew standpoint, so that we can get that timing down just right so we’ll be ready to go fly crew,” Atchison said.

Boeing plans to transport the capsule back to its Starliner factory and refurbishment facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where technicians will ready it for a future mission with astronauts. A separate spacecraft is being assembled at Kennedy for the Starliner’s first crewed test flight. Both vehicles are rated for up to 10 missions.

NASA has commercial crew contracts with Boeing and SpaceX to transport astronauts between Earth and the space station. The Starliner is Boeing’s commercial crew spacecraft.

Since 2011, the U.S. space agency has purchased seats from Russia for astronauts to travel to the space station, spending more than $80 million per round-trip ticket in recent agreements with Russia’s space agency.

New commercial crew ships developed by Boeing and SpaceX are intended to end U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz capsules for human transportation to the station. NASA signed contracts with Boeing and SpaceX in 2014 — valued at $4.2 billion and $2.6 billion, respectively — to begin flying crews into space before the end of 2017.

That schedule has been delayed more than two years. SpaceX accomplished a successful Crew Dragon test flight to the station in March, but the capsule was destroyed in an explosion during a ground test of its abort engines in April.

After introducing a fix to the cause the explosion, SpaceX is gearing up for a high-altitude launch abort test in January, and says it can be ready to fly astronauts to station soon after that.

NASA has not said whether it will require another unpiloted Starliner test flight after the problems that plagued the Orbital Flight Test, or whether agency official might press ahead with previous plans to fly astronauts Chris Ferguson, Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann on the next Starliner mission to the space station.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.