Hardware for two air-dropped Pegasus XL launchers previously purchased by Stratolaunch, a space launch company founded by the late billionaire Paul Allen, are now back under Northrop Grumman control and for sale to NASA, the Air Force, or commercial satellite operators, industry officials said.

Phil Joyce, vice president of space launch programs at Northrop Grumman, said this week that the company is trying to sell the launches using the two remaining Pegasus XL rockets, and officials plan to keep the Pegasus rocket’s L-1011 carrier jet flying for at least five or 10 more years.

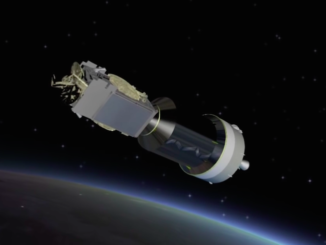

The airborne launch of NASA’s Ionospheric Connection Explorer, or ICON, scientific satellite Thursday night off Florida’s east coast is the final scheduled flight of a Pegasus XL rocket. Variants of the solid-fueled Pegasus rocket have flown on 43 satellite delivery missions since 1990.

“We actually purchased those back (from Stratolaunch),” Joyce said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “So they’re in a very advanced state of integration, which means they’re available for a very rapid response launch. We could launch one of those in six months, the second one probably in eight (months).

“We’ve been talking with NASA and several other customers about potential use of those for the near-term,” Joyce said. “There are some interesting opportunities.”

Orders of Pegasus rockets have tailed off over the last few years as new, lower-cost launch options become available to NASA, the sole Pegasus customer since 2008. Northrop Grumman’s rocket division, then known as Orbital Sciences, won a $56.3 million contract to launch the ICON mission in 2014. The launch has been delayed more than two years due to technical problems with the Pegasus rocket.

The Pegasus rocket is carried aloft by a modified L-1011 aircraft — the last of its kind still operational — to an altitude of 39,000 feet (11,900 meters), then released to fire into orbit.

The handover of the Pegasus rockets back to Northrop Grumman is another sign of a turbulent year at Statolaunch since Allen’s death last October. Stratolaunch is part of Vulcan Inc., a holding company established by Allen, a Microsoft co-founder.

In partnership with aircraft-builder Scaled Composites, Stratolaunch developed the world’s largest airplane and flew it on a two-and-a-half-hour test flight over California’s Mojave Desert in April.

The project was unveiled in 2011, when officials said the huge airplane — nicknamed “Roc” — would make its first flight in 2015 or 2016. Stratolaunch originally wanted to launch satellites using SpaceX-built rockets from the giant aircraft, then partnered with Orbital Sciences to develop a new air-launched booster. In 2016, Stratolaunch said it would launch Orbital’s Pegasus XL rocket, perhaps up to three on a single flight, using the new airplane, which has a wing span of 385 feet, or 117 meters.

Last year, Stratolaunch announced a roadmap for its own rocket family, beginning with a Medium Launch Vehicle that could debut in 2022 and lift up to 8,000 pounds (3,400 kilograms) of payload into low Earth orbit. Stratolaunch also revealed plans for a heavy-lift launcher and a space plane that could fire into orbit after a high-altitude drop from the aircraft.

Allen died last October from complications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and Stratolaunch said in January that it was ending development of its own rockets.

“We are streamlining operations, focusing on the aircraft and our ability to support a demonstration launch of the Northrop Grumman Pegasus XL air-launch vehicle,” a Stratolaunch spokesperson said in January.

Rocket motors and other components needed for the two Pegasus XL rockets are in place at Northrop Grumman’s facilities at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, officials said.

The first Pegasus XL demonstration launch with Stratolaunch was expected in 2020, officials said last year. In a press release after the April 13 test flight of the Stratolaunch aircraft, the company said the aircraft’s reinforced center wing can accommodate multiple launch vehicles.

But Stratolaunch has released no updates on future flight test plans.

The company’s website still lists the Pegasus rocket as one of its launch vehicle options.

Stratolaunch did not respond to Spaceflight Now’s questions regarding the transfer of the Pegasus XL rockets back to Northrop Grumman.

GeekWire reported last month that Stratolaunch recently listed nearly a dozen new job openings in Mojave and Seattle, including test pilot positions. That new hiring comes after Stratolaunch went through a round of staff cuts earlier this year after announcing the end of its own rocket development program.

While Stratolaunch’s plans are opaque, the Northrop Grumman is also facing headwinds with the Pegasus program.

A NASA decision in July to launch a future scientific satellite — the Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer, or IXPE — aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket meant Northrop Grumman missed one of its few near-term opportunities to capture a new launch contract for the Pegasus.

IXPE was originally designed to launch on a Pegasus rocket in 2021. But like all of NASA’s Explorer-class small science missions, the agency held a competition among certified launch providers to bid for the IXPE launch contract.

SpaceX won the contract for $50.3 million by bidding a Falcon 9 launch with previously-flown first stage booster, undercutting the most recent publicly-available price for a Pegasus. The Falcon 9 can carry 50 times more payload mass to low Earth orbit than the Pegasus.

The IXPE spacecraft was designed to fit inside the Pegasus rocket’s payload fairing envelope, and will weigh about 660 pounds (300 kilograms) at the time of launch. It’s designed to fly in an unusual low Earth orbit over the equator, at an inclination of 0 degrees.

The air-launched Pegasus XL rocket could have sent the IXPE spacecraft into such an orbit from a position over the Pacific Ocean near Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, the remote staging point for four previous Pegasus missions. The much bigger Falcon 9 has the capability to launch from a higher latitude at Cape Canaveral, and still deliver IXPE to its equatorial orbit target.

Pegasus rockets have launched from bases in California, Florida, Virginia, Kwajalein Atoll and the Canary Islands.

“The Pegasus was the first privately-developed space launch vehicle, and the first air-launched space launch vehicle with the first flight in 1990,” Joyce said Tuesday.

“This is mission 44,” he said, referring to ICON’s launch. “It’s a very robust system capable of 1,000 pounds to low earth orbit. It can launch anywhere in the world, and it’s one of our crown jewels.”

Joyce said Northrop Grumman is discussing Pegasus launch opportunities with NASA, payload developers and the U.S. military. The Pegasus could also be used for rideshare launches with multiple small satellites, but Northrop Grumman’s focus now is on finding a primary payload for the two remaining Pegasus rockets in the company’s inventory.

NASA’s Explorer line of small satellite missions have been reliable customers for the Pegasus rocket, but that string was broken when NASA selected SpaceX to launch the IXPE mission.

Nevertheless, Joyce said the Pegasus is available for future Explorer-class missions in heliophysics, the next of which is due for selection in 2021 for a launch in 2026. The Pegasus could also launch future “Venture-class” Earth science missions for NASA, he said.

“We do think there are opportunities for us on the space science front, as well as Air Force missions as well,” he said.

Besides SpaceX, other competitors in the Pegasus rocket’s class include new privately-developed smallsat launchers. Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket is already flying, and has launched on one dedicated mission for NASA, but it cannot lift as much payload mass into orbit as the Pegasus.

Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne, which is also air-launched with multiple launch sites available, closely matches the Pegasus rocket’s capabilities. The first LauncherOne orbital test flight could occur later this year.

“We’re always continuing to reinvent ourselves,” Joyce said. “We are looking at new launch vehicle concepts, as well as streamlining the launch vehicles that we have, the Minotaur, and our other offerings.”

Rocket Lab’s base price is less than $6 million per launch, and Virgin Orbit says the price of a LauncherOne mission is roughly $10 million to $15 million.

“We’re waiting to see how those guys do in the long term with the market that’s there to see if they can sustain those low prices,” Joyce said. “We expect some evolution on their side, probably coming up, and on our side, coming down.”

Joyce said Northrop Grumman’s solid motor production lines could accommodate future Pegasus missions beyond the hardware already manufactured for the next two rockets. Northrop Grumman’s missile defense programs, as well as the ground-launched Minotaur rocket, use some of the same solid rocket motors as the Pegasus.

“The Pegasus Stage 1 obviously has got the wing installed, so it’s a different motor,” he said. “But the second and third stage of Pegasus are actually common to those other programs, with the same production line.”

Northrop Grumman has three Minotaur rockets on contract with the Air Force to carry classified payloads into orbit for the National Reconnaissance Office, plus a suborbital mission for the Air Force. The next Minotaur rocket, a Minotaur 4, is scheduled for liftoff in February from Wallops Island, Virginia, on the NROL-129 mission.

Joyce said Northrop Grumman submitted a proposal to the Air Force’s Orbital Services Program-4 solicitation in August providing the military options to Minotaur and Pegasus rockets. OSP-4 will provide transportation to space for the military’s small and medium-sized satellite missions over the next nine years, and the Air Force says it anticipates awarding launch contracts for around 20 missions during that time.

“We’re participants in the OSP-4 contract, and there are going to be opportunities every year on that contract for Minotaur, and for Pegasus,” Joyce said. “Pegasus is one of the products on that one as well, for things that need an equatorial launch, or more launch flexibility in terms of the launch site.”

Joyce said Northrop Grumman recently purchased a second L-1011 aircraft to provide spare parts to the Pegasus rocket’s carrier jet, a signal that the company has no immediate plans to withdraw the Pegasus from the market.

“We’re looking out five or 10 years with the L-1011, and what parts do we need, being the only flying L-1011 on the planet,” he said. “We have the only trained pilots, we have the only trained mechanics for that aircraft, and we needed the parts.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.