Companies have until Nov. 1 to submit proposals to NASA for a human-rated lander that could be ready in time to carry astronauts to the moon’s surface by the end of 2024, and the agency is leaving open the option for contractors to develop a descent craft that would bypass the planned Gateway mini-space station in lunar orbit, at least for the first landing attempt.

The lunar lander, or Human Landing System, is critical to the Trump administration’s goal of returning humans to the moon’s surface by the end of 2024. NASA named effort after Artemis, the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology, after Vice President Mike Pence announced the 2024 goal in a speech March 26.

In the interest of speed, NASA has also relaxed requirements for the early human-rated lunar landers to be reusable. NASA eventually wants to reuse landers on missions ferrying astronauts between the moon’s surface and the Gateway space station in lunar orbit, where the spacecraft could be refueled for multiple landings.

And NASA has limited the time for companies to submit their proposals to one month.

“Thirty days,” said Marshall Smith, NASA’s director of human lunar exploration programs. “We know it’s crazy, but so is 2024, I suppose. So we’re all working very fast. I will tell that what we’ve done between March 26 to now probably would have taken the old NASA two years to do.”

“For HLS, every action we have worked has been streamlined in order to achieve to the surface of the moon by 2024,” said Lisa Watson-Morgan, the lander program manager at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

There’s little time to spare, and NASA is not planning to conduct an unpiloted demonstration of the lander without astronauts on-board before committing a human crew to a landing attempt.

NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel has warned against that strategy. During a September public meeting, the panel suggested that NASA and its contractors “consider the merits of including an uncrewed test of the Human Landing System prior to the first crewed mission as a major risk reduction exercise.”

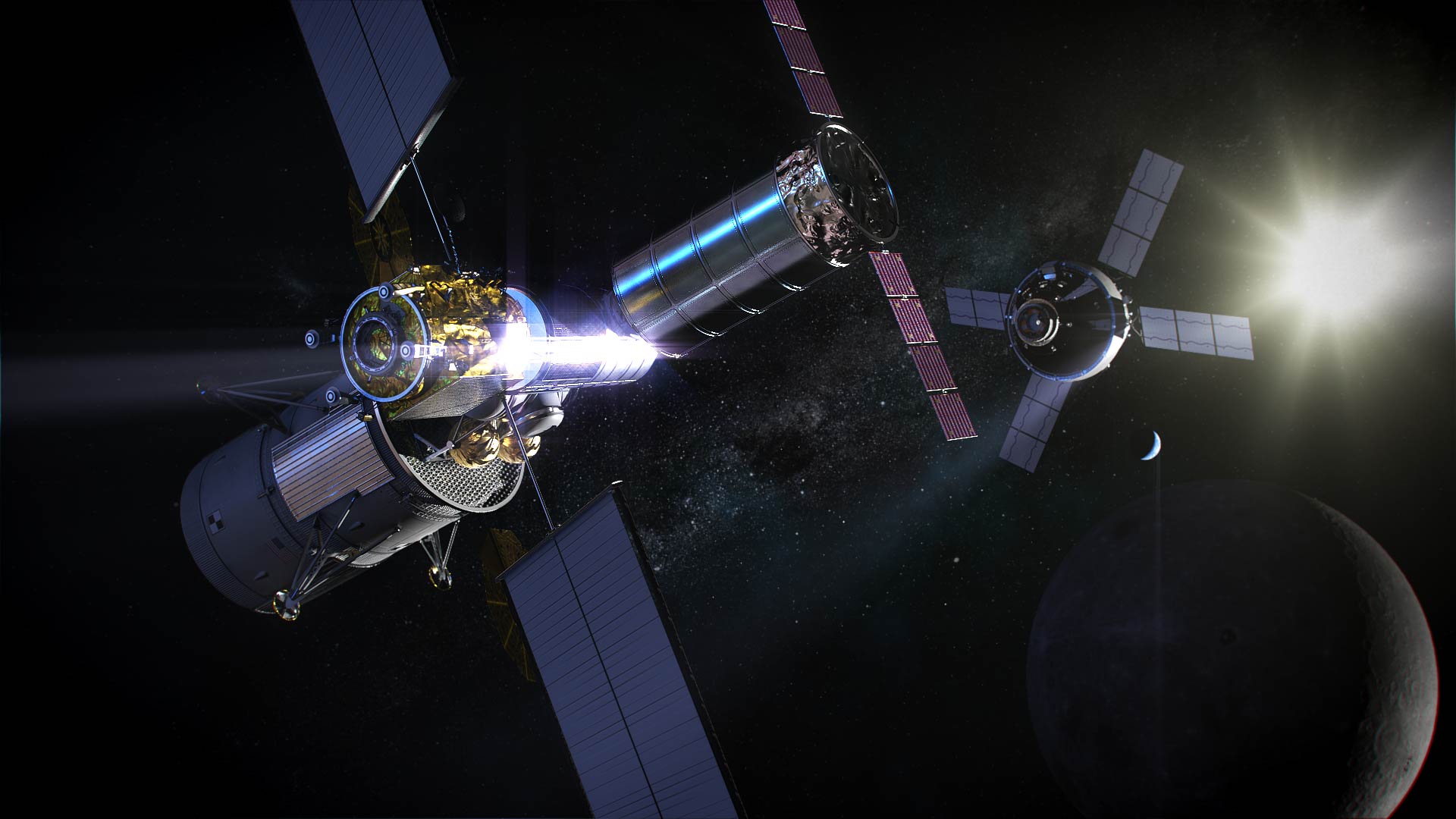

NASA’s approach to the Artemis program’s first lunar landing mission, which would target a landing near the moon’s south pole, includes several elements. First, at least two components of a new mini-space station lunar orbit, named the Gateway, would launch in 2022 and 2023 to generate electricity, provide propulsion and offer a limited habitat for astronauts.

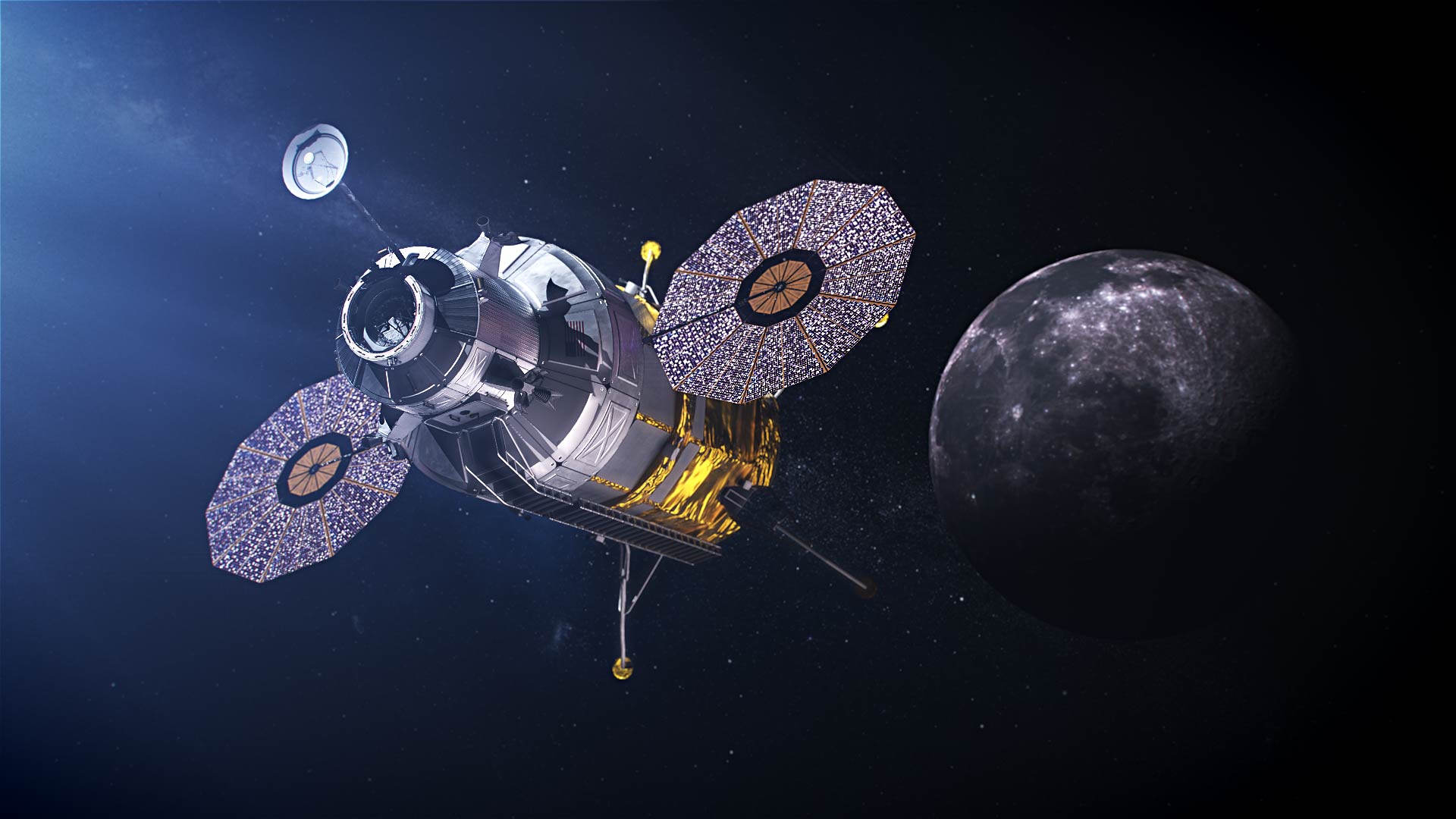

Components of a human-rated lunar lander would next launch, possibly on multiple rockets, to dock with the Gateway, where the pieces would be robotically assembled into a complete spacecraft. The lander will likely include two or three elements, such as a transfer vehicle to travel from the Gateway’s elliptical orbit around the moon to a closer distance, a descent module for landing, and an ascent vehicle to travel back to the Gateway.

After a checkout of the lander, the Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket would then launch an Orion crew capsule toward the Gateway station with four astronauts on-board in 2024. After Orion docks with the Gateway, two of the astronauts would transfer into the lander for descent to the moon.

Two test flights of the SLS/Orion vehicle to vicinity of the moon and back are planned before the 2024 landing attempt — one without a crew and one with astronauts on-board.

It’s an aggressive schedule, and some senior NASA leaders have demurred when asked about the likelihood of a crewed moon landing occurring by the end 2024.

NASA released a final solicitation, or broad agency announcement, to industry Sept. 30, seeking bids for a contract to design, develop and a lunar lander capable of carrying astronauts. Companies have until Nov. 1 to submit their proposals, and NASA aims to select up to four companies by January to begin 10-month design studies under firm fixed-price contracts.

The request for bids released Sept. 30 came after two draft solicitations, after which industry officials offered comments and proposed changes before the final announcement.

“We have a goal of awarding the contracts in January of 2020, and all this is really needed in order for us to make the schedule of 2024,” Watson-Morgan said an a Human Landing System industry day meeting Oct. 3.

Watson-Morgan said that NASA’s evaluation criteria for the HLS contracts will rank the contractors’ proposed technical approach as most important, followed by total price, and then the companies’ management approach.

In October 2020, NASA officials want to select two contractors from the design study award winners. Those firms will proceed with full development of their human-rated lunar landers, and NASA will later choose one for a landing attempt in 2024, and another for a moon landing in 2025.

NASA officials want to conduct lunar landing missions on a cadence of at least one per year after 2024.

Two astronauts are expected to be aboard for the Artemis program’s first two landing attempts, including — as NASA regularly mentions — the first woman to land on the moon.

Among other requirements, the landers for the 2024 and 2025 missions must provide the following capabilities:

- At least 1,907 pounds (865 kilograms) of payload delivered to the lunar surface, with a goal of 2,127 pounds (965 kilograms)

- At least 6.5 days on the lunar surface

- At least two spacewalks per mission, with goal of five spacewalks, using NASA-provided spacesuits

- At least 77 pounds (35 kilograms) of sample return capability, with a goal of 220 pounds (100 kilograms)

NASA will pick one or both of the lunar lander developers to work on a more “sustainable” lander design, a craft that will be able to carry at least four astronauts to the moon’s surface, operate during the two-week-long lunar night, and support longer-duration spacewalks. The more advanced lander could be ready to fly to the moon in 2026, and must utilize NASA’s Gateway in lunar orbit.

Space agency officials have moved ahead in recent months to streamline NASA’s contracting practices, shaving dozens of detailed requirements from an initial list that numbered more than 100. There are 26 performance requirements in the NASA lunar lander solicitation, covering basics like reliability thresholds, landing accuracy, communications requirements, and the need for windows on the spacecraft.

“After reviewing the comments, NASA removed requirements that industry perceived as potential barriers to speed while preserving all the agency’s human safety measures,” NASA said in a statement. “For example, industry stated that delivery of a high number of formal technical reports would require a company to spend considerable resources and incur undue schedule risk. Taking this into consideration, NASA has designed a less formal insight model that will be used for accessing critical contractor data while minimizing administrative overhead.”

It is up to the contractors to decide how to design their landers to meet NASA’s requirements.

“Reports still are valuable and necessary, but to compromise and ease the bulk of the reporting burden on industry, we are asking for access to the companies’ systems to monitor progress throughout development,” said Nantel Suzuki, the Human Landing System program executive at NASA Headquarters in Washington, in a statement. “To maximize our chances of successfully returning to the Moon by 2024, we also are making NASA’s engineering workforce available to contractors and asking proposers to submit a collaboration plan.”

NASA dropped requirements for the lunar lander on the 2024 mission to dock with the Gateway. Instead, the Orion spacecraft could dock directly with the lander in lunar orbit before starting the descent.

“We’re looking for innovative solutions,” Smith said in a Sept. 26 presentation to the National Academies’ Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board. “We’ve studied this quite a bit, and we’re looking for the best approach.”

And despite NASA’s preference for a reusable lander, the agency elected to waive that requirement for the 2024 and 2025 landing missions.

“We actually were requiring reusability, but we got some feedback from our contractors that … it might be one thing to build an ascent element that you say you’re going to take back and forth to the moon, say five or 10 times, but it’s another thing to certify that thing to stay in space for 10 years to be reused and refueled over and over again, and it might be cheaper to build another one,” Smith said.

“We’re letting that play and that trade pan out, but we will be using reusability across the board as much as we can, as long as it makes economic sense and we can look at how this affects our sustainability,” he said.

The HLS contractors will also be responsible for purchasing launch services to position their spacecraft in lunar orbit, with the option of using the Gateway as a staging point to connect the lander elements.

Commercial rockets currently operational do not have the lift capability required to send a lunar landing craft toward the moon in a single launch.

NASA says any rocket selected to loft lunar lander elements must be either certified under the NASA Launch Services II contract, or must have completed at least three successful launches of a common launch vehicle configuration before launching HLS hardware.

The fleet of U.S. rockets currently available under NASA Launch Services contracts include SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, and United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 and Delta 4. The roster will likely change before the 2024 mission.

If they desire, HLS contractors may negotiate with NASA’s SLS contractors to arrange for launch of the lunar lander — perhaps in a single piece — on an “SLS-derived commercial cargo vehicle solution,” NASA said.

Uncertainties about funding also cloud NASA’s lunar landing plans.

Moving forward with the lunar lander contracts, as NASA currently envisions, assumes the agency receives an extra $1 billion from Congress in its fiscal year 2020 budget, funding requested by the Trump administration earlier this year to kick-start lunar lander development efforts. The rest of the White House’s proposed $1.6 billion budget augmentation for the Artemis program included money to maintain the development schedule for the SLS and Orion programs to meet the Trump administration’s 2024 deadline.

NASA’s moon program was on a pace for a human lunar landing in 2028 before Vice President Mike Pence charged the agency in March to move that timeline up by four years.

The fiscal 2020 budget bill passed by the House of Representatives in June did not include the $1.6 billion in extra funding for the Artemis program. An appropriations bill approved by the Senate Appropriations Committee last month proposed $744 million for development of human-rated lunar landers, $256 million short of what NASA said it needed.

In response to questions Oct. 3 from industry, NASA officials said a funding shortfall for the lunar lander program could reduce the number of companies it can select for HLS contracts. NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has said the $1.6 billion budget augmentation is needed as a “down payment” for the 2024 moon landing goal, with the overall cost of the initiative expected to cost more than $20 billion.

NASA officials targeted a moon landing with astronauts in 2028 before Pence’s speech reset the schedule for 2024.

“In that previous plan, the government was going to buy an ascent element, a descent element, a transfer vehicle and a refueling (module), and we were going to go be the integrator,” Smith said. “We were going to go out for each of these parts. We were going to share the wealth, and everybody gets a piece of the pie. You know how it works.”

Smith said Pence’s announcement March 26 sent NASA’s lunar exploration team “into a tizzy.”

In the end, NASA decided to step back and give contractors more control over the lunar lander designs. Now, a single contractor will oversee the development of a lunar landing craft. Subcontractors could be charged with building the individual elements, or the transfer, descent and ascent modules could all come from the same company.

The final lunar lander solicitation released Sept. 30 is known as Appendix H in NASA’s contracting parlance. In May, NASA selected 11 companies under an earlier announcement known as Appendix E to conduct design studies and develop prototypes for lunar lander technologies.

The companies awarded funding through the Appendix E contracting round are expected to compete for human-rated lunar lander contracts, Smith said.

The Appendix E awardees included Aerojet Rocketdyne, Blue Origin, Boeing, Dynetics, Lockheed Martin, Masten Space Systems, Northrop Grumman, OrbitBeyond, Sierra Nevada, SpaceX and SSL, now known as Maxar.

“They’ve been working with us since June, working on the requirements we’ve been putting together for Appendix H, as well as all of the health and medical standards, and all the other requirements we need to make sure we can certify this for humans,” Smith said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.