NASA hopes to have a new leader for the agency’s human spaceflight directorate by the end of the year to replace Bill Gerstenmaier, who held the post for nearly 14 years before his reassignment in July amid the Trump administration’s push to land humans on the moon by 2024, a NASA official said Wednesday.

Until then, NASA will will not commit to a new target launch date for the first flight of the agency’s new heavy-lift rocket, named the Space Launch System, according to Ken Bowersox, who became the acting associate administrator for NASA’s human exploration and operations mission directorate after Gerstenmaier’s ouster in July.

Bowersox, a former astronaut who also had a stint as a SpaceX executive, said Wednesday that Jim Bridenstine, NASA’s administrator, and other senior NASA staff are “working really hard” and “talking to candidates” for Gerstenmaier’s permanent replacement.

“I think they’ve got a goal to actually be through with that process by the end of the year, and it’s hard work,” Bowersox said in a hearing before the Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee. “We want to give them all the time they need because we want them to find the right candidate.”

The chair of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel said Sept. 6 that having a permanent leader in charge of NASA’s human spaceflight directorate is “imperative” as the agency seeks to meet a 2024 deadline set by Vice President Mike Pence to return humans to the moon.

“As the agency moves on, we encourage NASA leadership to be cognizant of and deal aggressively with the impact of change,” said Patricia Sanders, chair of the safety advisory panel. “It is important to recognize the sense of uncertainly that accompanies a vacuum in a key leadership position and address the need for stable and credible direction in the future.”

NASA and contractor teams continue to press on with key components of the Artemis moon landing program, such as the Space Launch System, Orion crew capsule, a mini-space station in lunar orbit called the Gateway, and a human-rated lunar lander.

“NASA personnel are continuing to move forward and progress on the programs of record,” Sanders said. “That’s in their DNA. But having positive confirmation of a specific direction from a permanent leader is imperative, and a sense of uncertainly should not be allowed to linger in this critical time.”

Sanders said the panel received “anecdotal indications” that the change in leadership in NASA’s human spaceflight programs, ordered by Bridenstine, “signals that schedule is paramount and that extraordinary measures should be taken to maintain schedule, even at the potential expense of safety.”

“While NASA leadership has firmly stated that this is not the case, and in fact made decisions such as the continuation of the SLS green run (a full-up test-firing of the SLS core stage) that reinforce higher priorities than schedule, this message must be reiterated strongly and often,” Sanders said.

In August, Bridenstine said NASA is “looking wide and far” for a new human spaceflight chief at NASA Headquarters.

“We’re doing a nationwide search,” he said Aug. 21. “The challenge is … when it comes to these kind of activities, there’s very few people on the planet that have experience with human spaceflight missions, that have experience managing large programs. We are, at this point, wide open, looking at all the possible alternatives of various people with various types of expertise that could lead human exploration and operations. So at this point, we have not even begun to narrow the field.”

At that time, Bridenstine said NASA would start narrowing its list of candidates “in the coming weeks” Bowersox’s statement Wednesday pointed to potentially a longer schedule before a new human spaceflight chief will be named.

Bowersox said Wednesday that the first test flight of NASA’s Space Launch System, originally set for late 2017, is now projected to occur no earlier than the end of 2020.

The first SLS test flight with an unpiloted Orion capsule, designated Artemis 1, is more likely to occur at least several months into 2021, or perhaps even later.

The launch schedule for the first SLS test flight has been ever-changing since delays and cost overruns pushed the launch beyond a November 2018 commitment NASA made to Congress. NASA is still likely months away from coming up with a new official launch schedule.

Bowersox said that once NASA names the permanent head of the human exploration and operations mission directorate, the new manager will be charged to determine a new target launch date for Artemis 1, with a schedule that includes extra time to address unforeseen problems that may crop up during testing.

“Right after naming a permanent associate administrator, we expect, within a month or two, that person would have time to come up with a date that they can be ready to commit to Congress on,” Bowersox said Wednesday in response to a question from subcommittee chair Rep. Kendra Horn, D-Oklahoma.

“We’ve got a schedule we’re working to internally, but it’s … a best-case schedule,” Bowersox said.

Engineers at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans completed the structural integration of the first SLS core stage Thursday. Workers installed the engine section to the aft end of the 212-foot-long (64-meter) core stage, after difficulties fabricating and outfitting the engine section contributed to lengthy production delays at Michoud.

“NASA has achieved a historic first milestone by completing the final join of the core stage structure for NASA’s Space Launch System, the world’s most powerful rocket,” said Julie Bassler, the NASA SLS stages manager, in a statement. “Now, to complete the stage, NASA will add the four RS-25 engines and complete the final integrated avionics and propulsion functional tests. This is an exciting time as we finish the first-time production of the complex core stage that will provide the power to send the Artemis 1 mission to the moon.”

In the coming months, teams will install the four RS-25 main engines to the core stage. The engines are leftovers from the space shuttle program, and will consume super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen stored in the core stage propellant tanks.

“The earliest that we could launch Artemis 1, at this point, is roughly at the end of next year,” Bowersox said Wednesday. “We’ve got to get it out of the factory (at Michoud), which we think will happen at the end of this year.”

The core stage will ride NASA’s Pegasus barge from Michoud to the Stennis Space Center in southern Mississippi, where the stage will be lifted into a test stand for a series of fueling, pressurization and engine tests. The testing will culminate in a full-duration firing of all four RS-25 engines lasting more than eight minutes in a test called the “green run.”

Bowersox said the SLS core stage will undergo a minimum of five or six months of testing at Stennis before delivery to the Kennedy Space Center for launch processing, which will take another five or six months.

“If you start throwing in weather delays, any potential technical problems, anything that we have to fix after we fire the engines, that adds on extra time and it’s just hard to say exactly what will happen until we get there,” he said.

By the end of this year, NASA will have spent more than $16 billion on developing the Space Launch System since 2011. The figure does not include expenses on the Orion crew capsule or ground systems at the Kennedy Space Center to support SLS launch operations.

The behind-schedule launch vehicle was originally billed by NASA as the most cost-effective approach to developing a new heavy-lift rocket. The SLS uses leftover shuttle engines, strap-on boosters derived from the shuttle, an upper stage based on a design flown on United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4 rocket, and an existing factory and launch pad.

Despite the repeated delays, Government Accountability Office, a watchdog group, revealed in June that NASA has paid hundreds of millions of dollars of incentive-based award fees to Boeing and Lockheed Martin, the prime contractors for the SLS core stage and Orion spacecraft.

Bowersox said Thursday that the agency is re-evaluating its decisions on approving incentive-based payments to SLS and Orion contractors.

“I think we can all agree we’re not seeing the performance we want, so we should be looking at those,” he said.

Other key components for the first SLS test flight are ready for final launch processing. The SLS upper stage has been delivered to the Florida launch site, and all the segments of the SLS’s two solid rocket boosters have been filled with propellant and are ready for shipment to Cape Canaveral from a Northrop Grumman facility in Utah.

The SLS mobile launch tower is completing its final testing at Kennedy’s launch pad 39B before NASA declares it ready for stacking of the heavy-lift rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building. The ground systems at Kennedy are running behind their original schedules, but are predicted to be ready well in advance of the SLS core stage’s arrival in Florida.

Meanwhile, the Orion spacecraft for the Artemis 1 mission is at the Kennedy Space Center undergoing final assembly and testing in preparation for shipment to NASA’s Plum Brook Station in Ohio later this year. Engineers there will put the Orion crew module and its European-built service module through a thermal vacuum test in a chamber designed to replicate the airless, frigid conditions of space.

The Orion spacecraft will return to KSC ahead of final launch preparations for the Artemis 1 mission, which will send the craft into a distant orbit around the moon for several weeks before returning to Earth.

Assuming the Artemis 1 mission achieves its objectives, and launches by mid-2021, NASA could launch the Artemis 2 mission on the second SLS/Orion flight in 2022. Artemis 2 will carry up to four astronauts on a flight around the moon and back to Earth, setting the stage for the Artemis 3 mission as soon as 2024, which NASA says will attempt the first first landing by humans on the moon since 1972.

But the SLS and Orion programs are just part of the architecture required to put astronauts on the moon.

NASA is overseeing development of a mini-space station in lunar orbit named the Gateway, which will serve as a refueling station, temporary living quarters, and a safe haven for astronauts heading to the moon’s surface. NASA has selected Maxar Technologies to build a power and propulsion module for the Gateway equipped with high-power plasma thrusters for in-space maneuvers, and the agency selected Northrop Grumman for a sole-source contract to construct a mini-habitation module based on the company’s Cygnus space station supply ship.

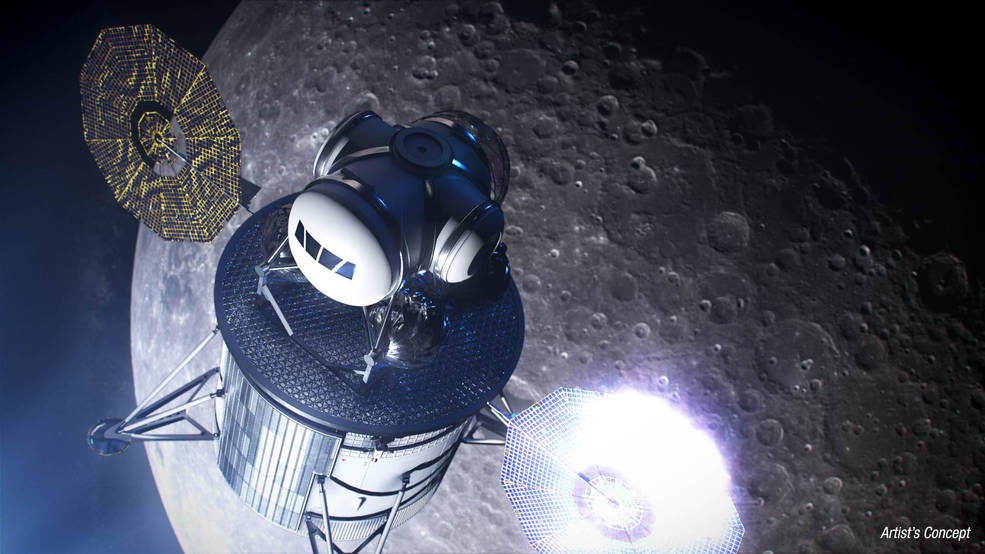

A human-rated lander is also needed to for a return to the moon by NASA astronauts.

NASA has released a pair of draft solicitations for the so-called Human Landing System in preparation for the release of a final solicitation in the coming weeks. NASA will request bids from U.S. companies to build a lunar lander with two or three elements — a descent stage, an ascent stage, and possibly a transfer vehicle to get from the Gateway to a low lunar orbit.

Bowersox said Wednesday that Congress must provide $1.6 billion in additional funding for NASA by the end of this year to enable the agency to kick-start development of a human-rated moon landing craft.

The Trump administration requested the extra $1.6 billion from Congress in May in an amendment to the White House’s fiscal year 2020 budget request.

Congress has not finalized an appropriations bill for fiscal year 2020, which begins Oct. 1.

The House passed its version of NASA’s 2020 budget legislation in June, but the bill did not include the additional $1.6 billion for the the Artemis program. The Senate is scheduled to mark up a 2020 appropriations bill for NASA next week, and any differences will be ironed out conference committee negotiations.

In the meantime, Congress will likely pass a continuing resolution before Oct. 1 to continue funding NASA and other government agencies through Nov. 21, giving lawmakers more time to approve a final 2020 appropriations bill.

Language in the House version of the continuing resolution does not have provisions for NASA to spend any of the extra $1.6 billion requested by the White House.

“The amendment, and the ability to spend that money if we have a continuing resolution, is critical to getting to the lunar surface in 2024,” Bowersox said. “We need to start our Human Landing System program.”

NASA aims to award contracts to up to four companies to begin work on a human-rated lander by the end of this year. Without the $1.6 billion funding augmentation, that won’t be possible, Bowersox said.

“For this year, what we need is that budget amendment so we can get the landing systems awarded, get those contracts out, because that’s our long pole right now for getting to the lunar surface,” he said.

“It slips after we go past the end of the year.”

After funding nine-month studies with up to four companies, NASA plans to down-select to two companies to continue working on the program through construction, launch and flight demonstrations of their lunar landers. The agency says it does not plan to conduct an unpiloted descent to the moon with the Human Landing System before putting astronauts on-board for the 2024 landing attempt.

In its most recent meeting, members of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel recommended NASA and its contractors reconsider that plan.

“The panel would also like to strongly suggest that NASA and the contractors consider the merits of including an uncrewed test of the Human Landing System prior to the first crewed mission as a major risk reduction exercise,” said Sandra Magnus, a former astronaut and member of the safety advisory board.

Like elements of the Gateway, components of the multi-stage lunar lander would launch on multiple lower-cost commercial rockets, not NASA’s Space Launch System, under the space agency’s current plan. The elements of the lander would be assembled and checked out at the Gateway before astronauts arrive on an Orion spacecraft.

Doug Cooke, a former NASA manager who also testified at Wednesday’s congressional hearing, said NASA’s plan to use commercial launch vehicles for Gateway and lander elements “doesn’t make much sense to me.”

Cooke argued that NASA should accelerate development of an enlarged Exploration Upper Stage, or EUS, for the SLS, an upgrade known as the SLS Block 1B. In that configuration, the Space Launch System could launch Orion crew vehicles and carry a lunar lander or other cargo on the same mission, rather than multiple launches of less expensive commercial rockets to pre-stage Gateway and lander components near the moon.

A “truth in testimony” document released with his prepared statement showed that Boeing, the prime contractor for the SLS core stage and the EUS, has paid Cooke more than $465,000 since 2017. In the document, his consulting work with Boeing is described as “sometimes related to the subject” of Wednesday’s hearing.

Cooke’s consulting work with Boeing was not mentioned during Wednesday’s hearing.

“I think it’s very important to be able to launch as much integrated hardware as you can without having to assemble it (in space),” said Cooke, a former NASA associate administrator for exploration. “Being able to launch an integrated lander all at once is a simpler, more straightforward approach, and it provides more. Having the large volume and mass capability allows it to be the size it needs to be for transporting the various elements to go to the moon.”

NASA still plans to introduce an Exploration Upper Stage for the SLS in the mid-2020s, but agency officials say using commercial rockets for the Gateway and lunar lander elements will be less expensive than upgrading the SLS and increasing the SLS launch rate.

Officials from NASA and the Trump administration have not said how much the space agency might need in 2021 and later years for the fast-track moon landing program. NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said in June the entire program would likely cost $20 billion to $30 billion, on top of the agency’s previously-planned budgets.

Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, D-Texas, and chair of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, said having a new associate administrator for NASA’s human spaceflight directorate is “critical to the success” of the agency’s exploration initiatives.

“We’ve been told not to expect a cost estimate or budget plan for the president’s moon program before next year,” she said. “Rhetoric about American leadership in space and advancing the role of women in spaceflight is all well and good, but it is not a substitute for a well-planned, well-managed, well-funded, and well-executed exploration program. Today, Congress has not been given a credible basis for believing that the president’s 2024 moon program satisfies any of those criteria.

“In short, if Congress is to support such a program, the administration is going to have to do a lot more to provide such evidence,” she said.

When asked during Wednesday’s hearing how confident he is that NASA will be able to land astronauts on the moon by 2024, Bowersox responded: “How confident? I wouldn’t bet my oldest child’s upcoming birthday present or anything like that. We’re working towards it as hard as we can.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.