NASA has announced that Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and OrbitBeyond won contracts to deliver science instruments and technology demonstration payloads to the moon’s surface in the first of a series of robotic missions preceding a human return to the moon.

The three companies are developing commercial lunar landers capable of hauling experiments, sensors and small rovers to the moon. Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and OrbitBeyond are among nine companies NASA selected last November to compete for contracts through the space agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program to ferry science instruments to the lunar surface.

NASA officials touted the CLPS contract announcements Friday as a stepping stone toward landing astronauts on the moon by 2024, a goal set by the Trump administration in March that moved up the agency’s earlier plans for a human lunar landing by four years. NASA has named the accelerated lunar landing program Artemis, goddess of the moon and sister of Apollo in Greek mythology.

“These CLPS providers are really leading the way for our return to the moon as part of the Artemis program, and these are precursor missions prior to us landing the first woman and the next man on the surface of the moon in 2024,” said Steve Clarke, associate deputy administrator for exploration in NASA’s science division.

Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and OrbitBeyond will share more than $250 million in contracts to deliver as many as 23 NASA-backed payloads to the moon. NASA plans to assign science and technology demonstration instruments to each company’s lander in the coming months.

The companies will aim to become the first private entities to successfully soft-land on the moon, and the first to achieve the feat would mark the first touchdown of a U.S. lander on the moon since the Apollo 17 mission’s takeoff from the lunar surface in December 1972.

OrbitBeyond says it can reach the moon next year

OrbitBeyond is a new name in the commercial lunar lander marketplace, but the New Jersey-based company leads a consortium of subcontractors who have designed and developed hardware for deep space missions. Team Indus, an Indian company, is leading Orbit Beyond’s lander engineering, and payload integration tasks will be managed by Honeybee Robotics, which built hardware for several NASA Mars landers.

According to OrbitBeyond, the company’s Z-01 lunar lander will be ready to land on the moon in September 2020. The company’s contract with NASA is valued at $97 million, and OrbitBeyond will fly up to four NASA payloads to the moon’s Mare Imbrium region, a lava plain on the lunar near side.

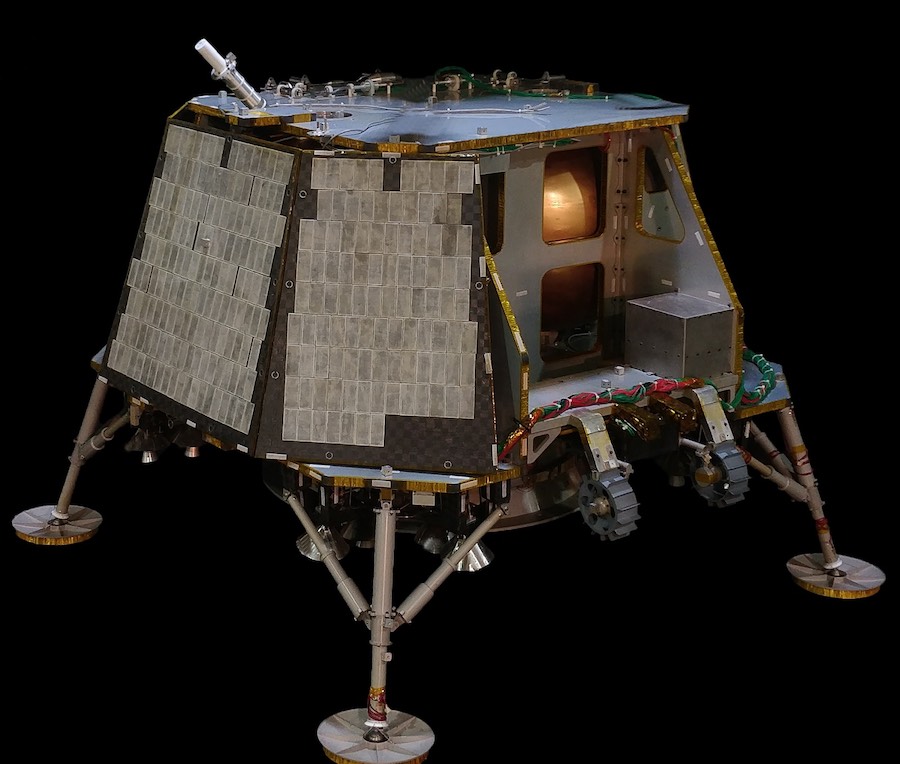

The OrbitBeyond lander is based on a design developed by TeamIndus, an Indian team that once competed for the Google Lunar X Prize. TeamIndus is not eligible to compete for CLPS contracts, which are open to U.S. companies.

While reusing the Indian team’s design, New Jersey-based OrbitBeyond plans to build its lunar landers in Florida. The Z-01 lander can carry about 90 pounds (40 kilograms) of payloads to the moon’s surface.

Siba Padhi, OrbitBeyond’s president and CEO, said NASA’s CLPS program will foster additional private investment in lunar transportation.

“We are very excited, and we hope to become a major player in cis-lunar space, and we look forward to assisting NASA in its mission to the moon (in) 2024,” Padhi said in a teleconference with reporters Friday.

OrbitBeyond plans to launch the lander on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

“The launch vehicle is something that is on our critical path, so to speak, because we want to get into the manifest, which is very busy over the next few years, so we’ll be engaging with SpaceX,” said Jon Morse, OrbitBeyond’s chief science officer.

In addition to a slate of NASA and commercial payloads, OrbitBeyond’s lander will also carry a small rover to for a test drive across the lunar surface.

“When we land, the rover drops down, and off it goes. It’s got a stereoscopic camera,” Morse said. “It’s for us, as a company, along with our partners, to learn about how to do surface mobility and operations.”

According to Padhi, OrbitBeyond is still in the process of securing full funding for development of the Z-01 lander. The company already has an engineering model of the spacecraft, and has made advance payments for flight hardware, Padhi said.

OrbitBeyond counts Ceres Robotics and Honeybee Robotics as key partners in its commercial lunar lander program.

Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander to soar to the moon in 2021

In Astrobotic’s case, Dynetics and Airbus Defense and Space are supporting development of the Peregrine lander, a robotic craft that will stand roughly 6.2 feet (1.9 meters) tall and 8.2 feet (2.5 meters) wide.

NASA’s contract for Astrobotic to deliver 14 of the agency’s science payloads to the moon is valued at $79.5 million. Astrobotic, headquartered in Pittsburgh, plans to land its first Peregrine mission by July 2021 at Lacus Mortis, a large crater with a surrounding lava plain on the near side of the moon.

The Peregrine is the first of a family of landers planned by Astrobotic. Like OrbitBeyond, Astrobotic once competed for the defunct Google Lunar X Prize, which ended last year without a winner.

“We haven’t landed on the surface of the moon as a nation in 46 years, so we need to go back,” said John Thornton, Astrobotic’s CEO. “We need to start small, and then go bigger and bigger.”

Thornton said Astrobotic completed a preliminary design review on the Peregrine last year. The company will build a structural test model and complete the Peregrine lander’s critical design review later this year, milestones that will wrap up the spacecraft’s design phase and mark the start of full-scale production in preparation for launch in June 2021.

“We’re now fully funded for the mission (and) ready to launch,” Thornton said. “We do have a small handful of kilograms remaining for payload customers … We’re going to be closing the manifest completely very, very soon, but overall we’re off and running and ready for a July of ’21 landing.”

Astrobotic previously had 14 payloads from eight nations booked for the first Peregrine landing, a roster that includes micro-rovers designed to drive short distances on the moon. NASA’s contract with Astrobotic doubled the mission’s payload manifest to 28 instruments.

Sharad Bhaskaran, mission director at Astrobotic, said the Peregrine lander will weigh around 3,100 pounds (1,400 kilograms) fully fueled for launch. The spacecraft will be able to haul up to 200 pounds, or 90 kilograms, of payload mass to the moon.

Astrobotic previously said the first Peregrine mission would ride into space as a secondary payload aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, but Thornton said Friday that the company will make a final launcher selection within a matter of weeks.

“We will ride as a secondary (payload),” Thornton said. “We’ve been in partnership with ULA for several years, and we’re in close communication with them. We’ve also had a relationship with SpaceX. We’re going to be announcing our launch literally within the next few weeks, so we’re well within the timeframe to hit our landing date, and we’re not too worried about that.”

Intuitive Machines leans on NASA-developed landing technology

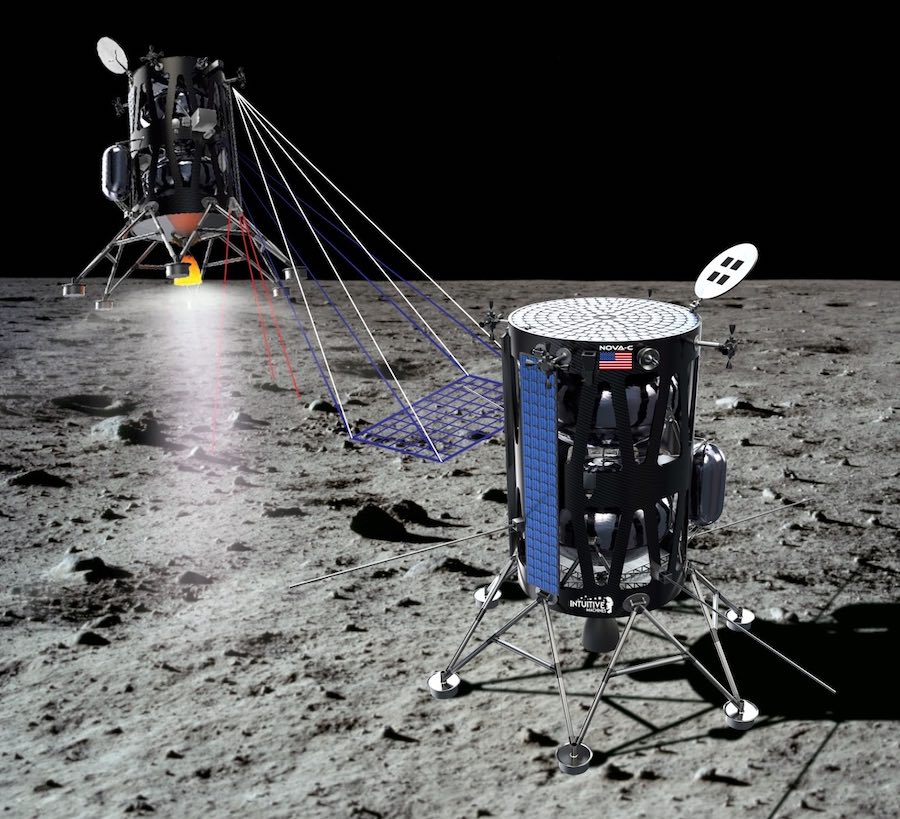

Intuitive Machines has the largest lander of the three companies that won NASA payload delivery contracts last week.

Standing roughly 10 feet (3 meters) tall, the Nova-C lander can deliver up to 220 pounds (100 kilograms) of scientific and technology demonstration payloads to the moon. Houston-based Intuitive Machines says the Nova-C lander can reach any location on the moon, and like Astrobotic’s Peregrine spacecraft, will be ready for its first lunar landing by July 2021.

“This is a fast-paced program by design, so the schedule (of) two years is aggressive in every case,” said Steve Altemus, president and CEO of Intuitive Machines.

Intuitive Machines was founded in 2013 by Kam Ghaffarian, an aerospace industry entrepreneur, with Altemus and Tim Crain, both former NASA engineers.

NASA’s payload delivery contract with Intuitive Machines is valued at $77 million, covering the launch and landing of up to five instruments at Oceanus Procellarum, or the Ocean of Storms, a vast lava plain on the near side of the moon.

While the landers developed by OrbitBeyond and Astrobotic will use hydrazine fuel, a liquid that can be stored in space at room temperature, Intuitive Machines plans to use a landing engine fed by super-cold liquid methane and liquid oxygen. The use of cryogenic propellants adds complexity, particularly in keeping the liquids from warming up in sunlight, but the engine offers higher performance and could be a building block toward larger landers, Altemus said.

The Nova-C lander’s engine can be throttled to control its descent, Crain said, and the craft also carries technology to avoid hazards like craters, boulders and steep slopes.

“We took some known risks on our side for a cryogenic propulsion system … because of its scaleability, and we’re proficient in that,” Altemus said. “So we have some challenges in cryo fluid managemenet for the development of the lunar lander, but we think we have those well in hand.”

“I’m proud to say that we’re firing our LOX/methane flight engine with the flight software on a flight processor currently,” Altemus said. “We’ve had test firings last week and next week, and all through the summer, we’ll be doing that to refine the performance of the propulsion systems and the software.”

Altemus said Intuitive Machines has a “fully designed lander” and is “fully funded” to support a landing on the moon in July 2021.

The Nova-C traces much of its design heritage to Project Morpheus, a tech demo project led by engineers at NASA’s Johnson Space Center that tested a methane-fueled descent engine, hazard avoidance sensors, and other lunar landing hardware during a series of tests at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida from 2012 through 2014.

Intuitive Machines plans to launch the Nova-C lander as the primary payload in a multi-mission rideshare launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, Altemus said.

NASA officials said the agency plans to issue more task orders to the nine CLPS providers over the next few years, and potentially will add more companies to the list of contractors eligible to compete for lunar payload delivery services.

“We’re looking at hopefully building up to a cadence of a couple of missions per year, and then maybe out in the ’23 or ’24 timeframe (raising) that cadence to three or four missions per year going to several locations on the surface on the moon,” Clarke said.

One critical capability NASA wants commercial companies to develop and demonstrate is surface mobility. NASA has asked the nine CLPS providers to submit proposals for study contracts outlining their plans to develop rovers, which could be used as scouts near the lunar south pole, where the Trump administration has challenged NASA to land astronauts by 2024.

“This is the start of building a robust cadence of missions returning to the moon. We’re going to do science investigations, we’re going to do technology demonstrations, we’re going to do ISRU (In Situ Resource Utilization). One important thing about this is a lot of what we are doing, we are going to advance for human exploration on the surface of the moon. A lot of what we do for precursor missions before 2024 are going to help inform that.”

But the commercial lunar lander program is risky. None of the three CLPS contract winners have ever launched a space mission, but their lunar lander projects include partnerships with major aerospace companies.

The first private entity to attempt a lunar landing was SpaceIL, an Israeli non-profit organization that developed the Beresheet lander, which crashed on the moon during a landing attempt in April. The Israeli team is in the early stages of planning a follow-up mission named Beresheet 2.

“My confidence is high that these three companies here will succeed,” Clarke said. “Like with anything that’s hard — space travel is hard — I don’t doubt that there will some technical challenges along the way over the next two years, but that’s to be expected … I have no doubt that we’ll be seeing successful landings on the moon within the next two years.”

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has compared the CLPS program to “taking shots on goal,” a sports analogy where not every shot is expected to land in the net.

Clarke said he believes commercial industry is mature enough to make the CLPS program is successful, but said “time will tell if this model works.”

NASA received eight proposals from the roster of CLPS providers, and the agency settled on Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and OrbitBeyond.

“I have high confidence in these three companies, based on the fact that we put out delivery task orders and we received proposals in, and these three companies showed what I would call credible technical plans, well thought out, with schedule and cost commensurate with their plans, and they identified the risks along the way,” Clarke said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.