On its first nighttime launch, Rocket Lab’s Electron booster climbed into orbit Sunday from New Zealand with a trio of small U.S. military payloads, demonstrating the privately-developed rocket’s ability to help meet the Air Force’s growing demand for smallsat launches.

Standing 55 feet (17 meters) tall, the two-stage Electron rocket lit nine Rutherford main engines at 0600 GMT (2 a.m. EDT) Sunday and fired away from Rocket Lab’s commercial launch base on New Zealand’s North Island.

The satellite carried three small satellites, ranging in side from a tissue box to a small refrigerator, for the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command. The Space Test Program, a unit based at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico which provides access to space for military experiments, managed the multi-satellite launch with Rocket Lab.

Sunday’s mission was the first by Rocket Lab for the U.S. Air Force.

Heading east over the Pacific Ocean shortly after sunset in New Zealand, the all-black carbon-composite Electron launcher shut down its first stage engines around two-and-a-half minutes into the flight, and jettisoned the booster to fall into the sea.

A single Rutherford engine ignited on the Electron’s second stage to place the mission’s three smallsat payloads into a preliminary transfer orbit around nine minutes into the flight. The rocket’s Curie upper stage separated a few seconds later, setting up for a nearly three-minute burn beginning at T+plus 49 minutes to place the mission’s three payloads into a targeted 310-mile-high (500-kilometer) orbit with an inclination of 40 degrees to the equator.

Rocket Lab’s live video webcast ended before the Curie kick stage’s orbit circularization burn, but Peter Beck, the company’s founder and CEO, confirmed the successful maneuver and deployment of the rocket’s three satellite payloads in a tweet.

“Perfect flight, complete mission success, all payloads deployed!!” Beck tweeted.

Rocket Lab intended to launch the mission Saturday, but officials delayed the launch to conduct additional checks on the payloads. The mission’s total payload weight — around 400 pounds (180 kilograms) — made it the heaviest launch by Rocket Lab to date.

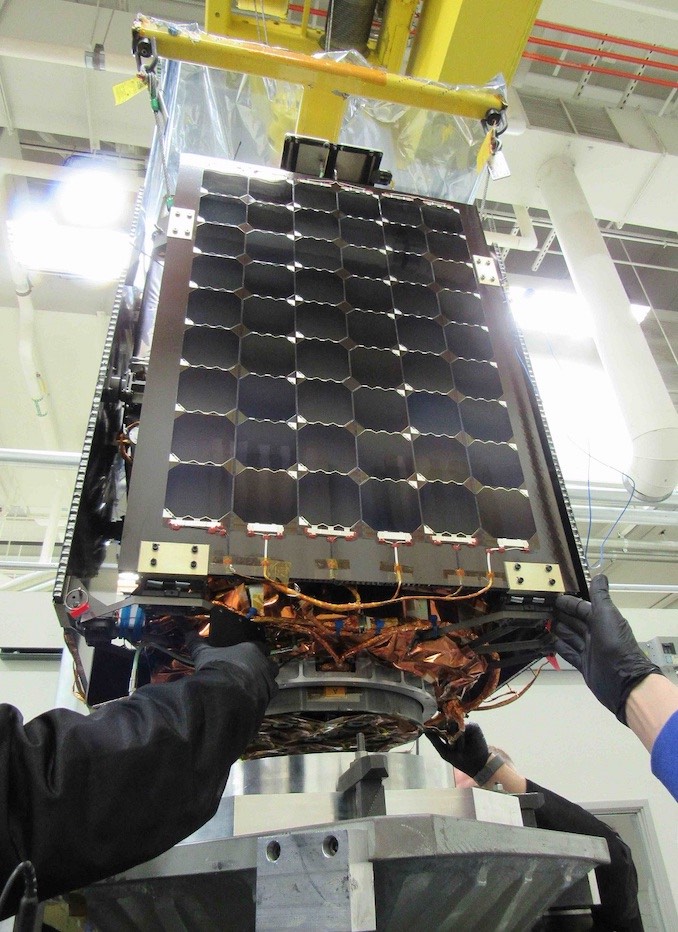

The biggest of the satellites launched Sunday is named Harbinger.

Built by York Space Systems in Denver, the Harbinger mission is sponsored by the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command. The roughly 330-pound (150-kilogram) spacecraft hosts several technology demonstration payloads, including a synthetic aperture radar for all-weather Earth observation and a high-data-rate communications link to transmit the radar imagery to users on the ground.

The Harbinger satellite’s radar imaging instrument comes from ICEYE, a Finnish company which has built and launched its own commercial radar observation smallsats. The radar imaging payload on Harbinger “provides commercial access to timely and reliable Earth observation data and is capable of imaging any location on Earth at regular intervals, day or night, regardless of cloud cover,” according to the Army’s fact sheet on the mission.

A high-speed laser communications terminal on Harbinger from BridgeSat will downlink the radar imagery, demonstrating a rapid data collection capability that could be used by tactical military forces on the battlefield.

Harbinger was joined on the Electron launch by two tech demo CubeSats named SPARC-1 and Falcon ODE.

The Space Plug and Play Architecture Research CubeSat-1 — about the size of a briefcase — is a joint U.S.-Swedish military research nanosatellite.

SPARC-1 will test miniaturized avionics, a software-defined radio system, and a visible camera. The mission’s U.S. sponsor is the Air Force Research Laboratory, which developed the mission in partnership with the Swedish Defense Materiel Administration.

The six-unit CubeSat’s prime contractor was ÅAC Microtecs, a Swedish smallsat manufacturer.

The smallest payload launched Sunday was the Falcon Orbital Debris Experiment, a one-unit CubeSat a bit larger than a Rubik’s cube. The Falcon ODE spacecraft, developed at the U.S. Air Force Academy, will release two stainless steel ball bearings in orbit, which will become calibration targets for ground-based space surveillance radars.

The Air Force booked Sunday’s mission with Rocket Lab, designated STP-27RD by the Space Test Program, in 2017 under the military’s Rapid Agile Launch Initiative, or RALI, program.

The STP-27RD mission was the first for the RALI program, which procured launch services from commercial providers to offer military satellites a faster ride to orbit.

Air Force officials said last month that five RALI launches were planned before the end of 2019, including the STP-27RD mission with Rocket Lab’s Electron launcher and a flight on Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne vehicle later in the year. The five missions, including Sunday’s STP-27RD launch, will provide access to space for 21 research and development satellites, according to Lt. Col. Andrew Anderson, chief of the Department of Defense Space Test Program branch.

The RALI missions “will put DoD experiments on orbit and demonstrate new launch vehicles from new commercial providers,” Anderson told reporters in a conference call last month.

Sunday’s launch marked the sixth flight of Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket since 2017, and the second this year. Rocket Lab, headquartered in the United States with factories in Southern California and Auckland, New Zealand, aims to launch about one mission per month through the rest of 2019, ramping up to a cadence of every two weeks by the end of the year.

Rocket Lab charges less than $7 million for its launches, and Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne, which has not yet flown and will drop from an airborne carrier jet, sells for approximately $12 million per flight.

Both price points are a fraction of the cost of a launch on a larger rocket. Smallsats riding on bigger boosters usually fly as second-class payloads, with orbits and schedules driven by the needs of a higher-priority spacecraft on the same flight.

“We are seeing a lot of bang for our buck for these venture-class small launch service providers,” said Col. Bernard Brining, director of the Space Test Program. “We do see value for the Space Test Program. As the director, I’m able to get a lot (more) payloads on orbit for a very low cost.”

Numerous companies — more than 100, by some counts — are developing light-class small satellite launchers, but Rocket Lab is the first of a new generation of commercial firms to debut a new orbital-class rocket.

The wave of new private smallsat launch companies has left many in the industry wondering how many will survive the challenges of fundraising, technical development, and an ever-evolving market.

“I think the market is still shaking out here, and we are trying to participate in it,” said Col. Robert Bongiovi, director of the launch enterprise systems directorate at the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center. “And if the market will support many (companies), we are supporting contracts for many because … that’s going to be very useful for us to get our needed national security payloads to space in the small launch class.”

So far, most of the military’s small satellites have been experimental. In the future, small spacecraft could play more critical roles in the U.S. military’s communications, navigation, and surveillance fleets.

“While many of the small satellites we have launched to date have been research and development satellites, this will change in the future,” Bongiovi said.

“What we would really like to see … is the ability to start using them not just for experimental launches, which we’ll continue to keep doing, but also for more operational prototypes, and eventually operational systems,” Bongiovi said. “I think there’s absolutely a lot to be said (about) these smaller launch vehicles on their ability to provide some of the resiliency that we all feel we’re going to need.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.