The U.S. Air Force was tracking at least 270 debris fragments created by an Indian anti-satellite missile test, but the debris field posed no immediate threat to the International Space Station or most other satellites in low Earth orbit, a senior U.S. military official said Wednesday in a congressional hearing.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the successful anti-satellite test — named “Mission Shakti” — in a televised address Wednesday, heralding the achievement as a proud moment for India, which became the fourth country to demonstrate such a capability after the United States, Russia and China.

But the test quickly raised concerns about space junk, and the deputy commander of U.S. Air Force Space Command told lawmakers Wednesday the military’s satellite tracking radars were monitoring at least 270 pieces of debris left over from the collision of the Indian anti-satellite missile and its target in low Earth orbit.

Each fragment from the shattered satellite was traveling around the Earth at more than five miles per second. A violent impact with another object at the speed could take out a satellite and generate even more debris.

The missile launch occurred at 0539 GMT (1:39 a.m. EDT; 11:09 a.m. Indian Standard Time) Wednesday, according to Lt. Gen. David Thompson, vice commander of Air Force Space Command. Thompson said in a hearing Wednesday afternoon before a subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee that U.S. officials were aware of the upcoming missile launch as it happened.

“First of all, let me say clearly, it was detected, characterized and reported by Air Force systems, missile warning systems, and our airmen at Buckley Air Force Base,” Thompson said.

“Immediately after the test struck the target vehicle, the Joint Space Operations Center and the Air Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron began collecting information about the break-up of the vehicle,” Thompson said. “Currently, they are tracking about 270 different objects in the debris field. Likely, that number is going to grow as the debris field spreads out and we collect more sensor information.”

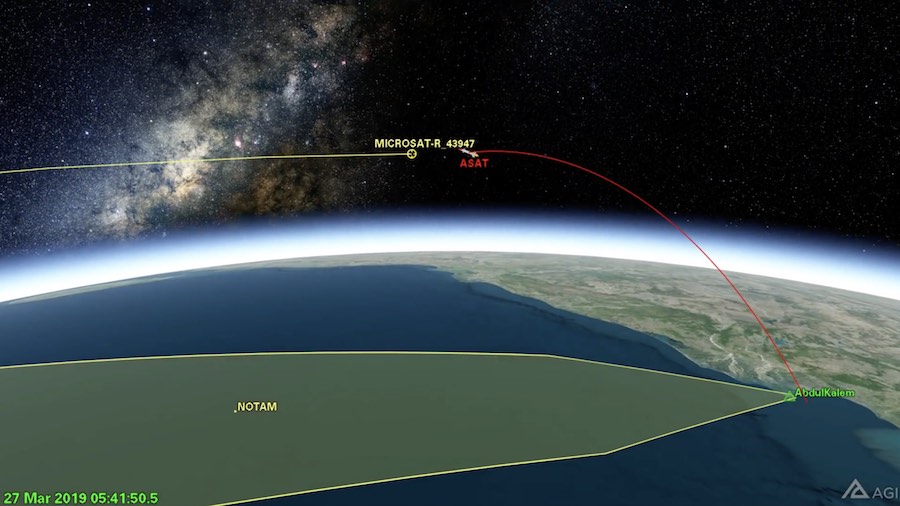

Indian officials said the anti-satellite missile, a modified rocket derived from the country’s ballistic missile defense program, launched from Abdul Kalam Island on India’s east coast and struck its target roughly 186 miles (300 kilometers) above Earth, disintegrating the satellite in a high-speed collision.

The target for the test was likely the Indian military’s Microsat-R satellite, which lifted off Jan. 24 on an Indian Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle. The 1,631-pound (740-kilogram) Microsat-R spacecraft, which Indian officials described in January as an “imaging satellite,” was deployed into an unusually low polar orbit around 170 miles (274 kilometers) above Earth for the Defense Research and Development Organization, the Indian military agency which also conducted Wednesday’s anti-satellite test.

Analytical Graphics Inc. posted a video Wednesday with illustrations of how the anti-satellite test occurred.

Thompson told lawmakers Wednesday that military officials will provide warning to commercial and international operators if their satellites are at risk of a collision with debris from Microsat-R, as the U.S. military does for all space traffic.

“We do know that altitude at which it occurred, and we immediately started providing public notice on our Space Track website and will provide direct notification to spacecraft operators if those satellites are under threat. I will also say, at this point in time, the International Space Station is not at risk,” Thompson said. “That’s a thing that we do and provide warning routinely.”

Microsat-R’s low orbit was below the altitude of the International Space Station and nearly all other operational satellites. Indian officials said they selected the low altitude for the anti-satellite test to ensure the fragments scattered by the collision are quickly pulled back into Earth’s atmosphere by aerodynamic drag.

Brian Weeden from the Secure World Foundation said most of the debris created during Wednesday’s anti-satellite test will naturally re-enter the atmosphere within several weeks. But some of the small fragments could have been ejected to higher altitudes from the energy of the collision, meaning they could stay in orbit longer, according to Weeden, a former Air Force officer who worked in space surveillance.

Anti-satellite testing has long been a point of controversy, raising concerns about the use of offensive weapons in space and the consequences of adding to the growing problem of space junk.

In 2008, the U.S. military destroyed a defunct spy satellite with a sea-launched missile at an altitude of around 150 miles (250 kilometers). Officials then said they destroyed the failed satellite to ensure a block of frozen toxic hydrazine fuel on-board did not threaten anyone on Earth if the spacecraft fell back into the atmosphere for an uncontrolled re-entry. Most of the debris from the satellite, designated USA-193, re-entered within hours or days, but it took more than 18 months for all of the material tracked by the military’s radars to fall out of orbit, according to Weeden.

The U.S. Air Force previously achieved a successful anti-satellite test in 1985, using an air-launched missile fired by an F-15 fighter plane to destroy a U.S. research satellite in orbit. The last debris from that test re-entered the atmosphere in 2004, according to data compiled by Weeden.

China destroyed one of its own weather satellites in an anti-satellite test in 2007. The target satellite for that test, named Fengyun 1C, was orbiting an altitude of more than 500 miles (800 kilometers), where the density of air molecules is much lower than in orbits closer to Earth.

The Chinese anti-satellite test produced more than 3,000 trackable debris fragments, most of which are still in orbit and occasionally threaten other spacecraft.

“We have intentionally chosen lower altitudes … as a responsible nation to see that all the space assets are safe and the debris are decaying very fast,” said G. Satheesh Reddy, director of India’s Defense Research and Development Organization, or DRDO. “This is the intention, but we have the capability to do this in the complete low Earth orbit … up to 1,000 kilometers-plus (600 miles-plus).”

A computer simulation of the break-up of the Microsat-R satellite conducted by Hugh Lewis, head of the Astronautics Research Group at the University of Southampton in England, showed how the energy of an anti-satellite missile collision could propel shards of debris into higher orbits.

India ASAT test: quick simulation of the breakup of MICROSAT-R & resulting #spacedebris. Guesses for intercept speed & projectile mass. Characteristics of fragments shown come from distributions described in Johnson et al. 2001, ASR (28/9), 1377-1384. REPEAT: it’s a simulation pic.twitter.com/6aFS23GFbb

— Hugh Lewis (@ProfHughLewis) March 27, 2019

In a series of tweets about the anti-satellite test, Modi wrote that the “entire effort is indigenous” and that India “stands tall as a space power.”

“It will make India stronger, even more secure and will further peace and harmony,” Modi tweeted.

Jim Bridenstine, NASA’s administrator, said in a separate congressional hearing Wednesday that he is concerned about the debris generated by anti-satellite tests.

Without identifying India, or mentioning the intentional destruction of satellites by China and the United States since 2000, Bridenstine said that “creating debris fields intentionally is wrong.”

“That’s an important point because some people like to test anti-satellite capabilities intentionally and create orbital debris fields that we today are still dealing with,” he said in a hearing in the House of Representatives. “And those same countries come to us for space situational awareness because of the debris field that they themselves created, and that’s being provided by the American taxpayer, not just to them, but to the entire world, for free.

“So the entire world needs to step up and say, ‘If you’re going to do this, you’re going to pay a consequence.'” And right now, that consequence is not being paid.” Bridenstine said.

One satellite company that often buys rides on Indian rockets condemned Wednesday’s anti-satellite test.

“Space should be used for peaceful purposes, and destroying satellites on orbit severely threatens the long-term stability of the space environment for all space operators,” San Francisco-based Planet said in a statement. “Planet urges all space-capable nations to respect our orbital commons.”

Planet operates a fleet of more than 100 Earth observation satellites, ranging in size from a shoebox to a mini-refrigerator. Many of Planet’s imaging satellites have launched on Indian PSLV missions, and 20 more are due for liftoff Sunday on the next PSLV flight, making Planet one of the biggest foreign export customers for India’s space program.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.