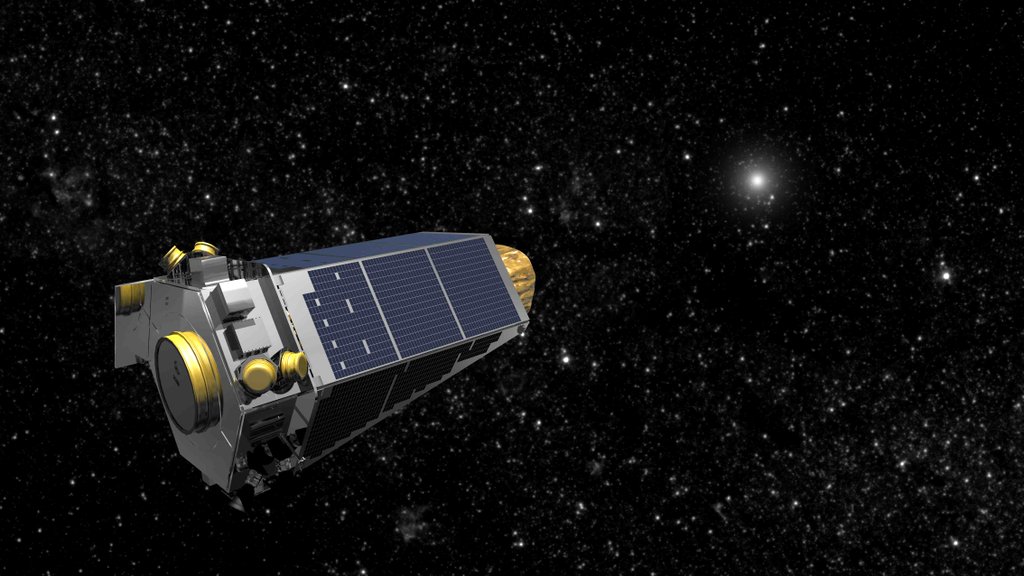

Ground controllers have beamed the final commands to NASA’s Kepler telescope, turning off the spacecraft’s transmitters and disabling the craft’s automatic recovery software after the planet-hunting observatory ran out of fuel last month.

The last signals to Kepler were broadcast from a control center at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, or LASP, at the University of Colorado in Boulder, through NASA’s Deep Space Network, on Thursday evening.

Engineers commanded Kepler to turn off its radio transmitters, a standard procedure during deactivation of a space mission to ensure errant signals do not interfere with communications using the same or similar frequencies. The commands also prevented Kepler’s on-board computer from trying to switch the transmitters back on and contact Earth.

“Because the spacecraft is slowly spinning, the Kepler team had to carefully time the commands so that instructions would reach the spacecraft during periods of viable communication,” NASA said in an update Friday. “The team will monitor the spacecraft to ensure that the commands were successful.”

NASA announced Oct. 30 that Kepler had run out of fuel and no longer had the pointing stability to search for planets around other stars.

Launched in 2009, Kepler is circling the sun around 94 million miles (151 million kilometers) from Earth. On its current path, Kepler is flying a bit farther from the sun than Earth, and traveling around the sun a bit slower than Earth.

The spacecraft will get farther way from Earth over the coming decades, before eventually Earth starts to catch back up. In 2060, Kepler will return to the vicinity of Earth — but well outside the orbit of the moon — and the planet’s gravity will tug the telescope into an orbit a bit closer to the sun, and one that moves faster than Earth.

The reverse will happen in 2117, when Kepler and Earth converge again and gravity pushes the spacecraft into the farther, slower orbit. The pattern is predicted to continue for the foreseeable future, according to NASA.

Meanwhile, scientists continue analyzing data collected during Kepler’s nine-year, $692 million mission.

Kepler collected its last science observations in September, ending a run that observed more than 530,000 stars and returned 678 gigabytes of data. Kepler’s discoveries also helped astronomers write nearly 3,000 scientific papers, a number that will continue to climb.

Astronomers using data collected by Kepler confirmed the existence of 2,681 planets orbiting other stars, with another 2,899 planet candidates in the pipeline that could be confirmed with follow-up observations.

“We found small potentially rocky planets around some of these bright stars, and those are now prime targets of current and future telescopes so we can move on to see what these planets are made of, how they are formed, and what their atmospheres be like,” said Jessie Dotson, Kepler project scientist at Ames.

“While we have ceased spacecraft operations, the science results from the Kepler data will continue for years to come,” she said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.