NASA’s Kepler telescope has run out of fuel and ended science operations, closing out a pioneering decade-long mission that showed planets are commonplace across our galaxy, agency officials said Tuesday.

The observatory’s supply of hydrazine has run low for months, but controllers noticed a dramatic drop in fuel pressure earlier this month, indicating Kepler no longer has enough propellant to maintain the precise pointing required to search for planets around other stars, or exoplanets.

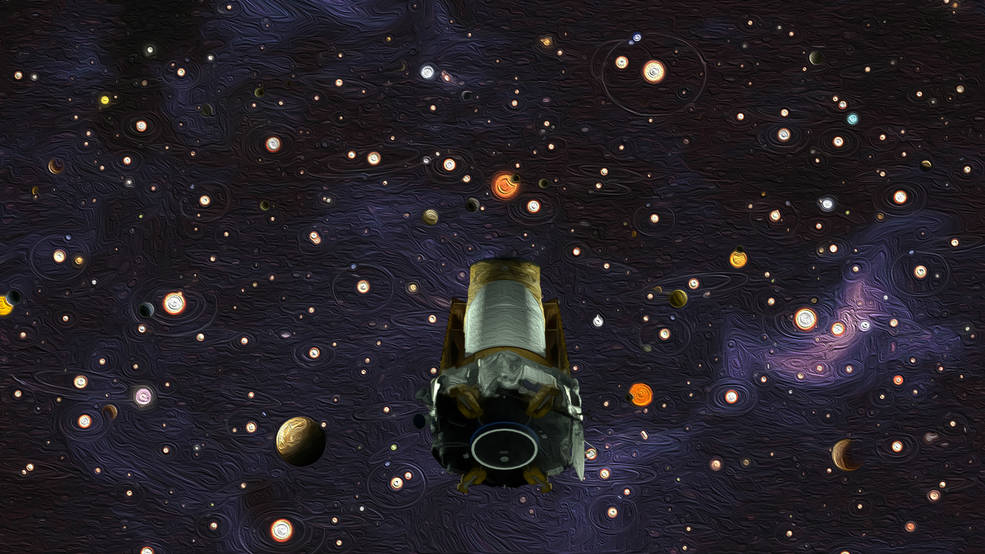

Kepler’s observations since its launch in March 2009 have led astronomers to confirm the existence of 2,681 planets orbiting other stars, with another 2,899 planet candidates in the pipeline that could be confirmed with follow-up observations.

“In 2009, the Kepler mission launched, and immediately our team began detecting a wide variety of planets,” said Bill Borucki, a retired astronomer who led Kepler’s science team through development and its early years of science observations. “In its nine-and-a-half years of operation, the Kepler mission has been an enormous success.

“We’ve shown that there are more planets than stars in our galaxy, that many of these planets are roughly the size of the Earth, and some, like the Earth, are at the right distance from their star so there could be liquid water on their surface, a situation conducive to the existence of life,” Borucki said.

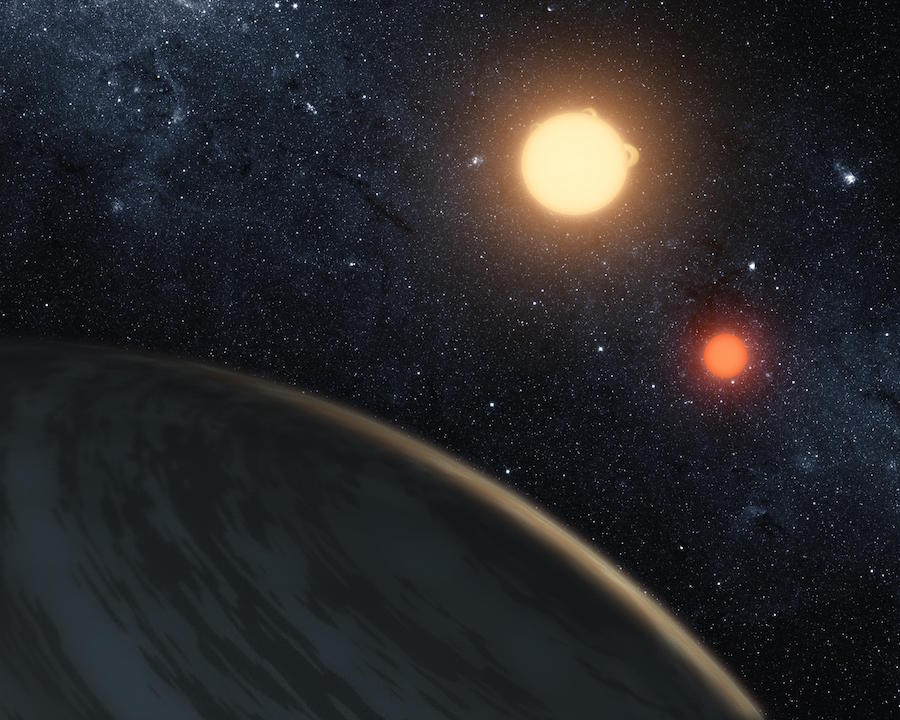

Astronomers discovered a variety of planet types with Kepler, ranging from so-called “hot Jupiters” to “super Earths,” and a handful of rocky planets believed to reside at the right distance from their parent star to maintain liquid water.

“Hot Jupiters” are gas giants that orbit hellishly close to their stars, often completing one lap in a matter of days with surface temperatures above 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,100 degrees Celsius).

Kepler also found numerous planets between the size of Earth and Neptune. Such planets that orbit the right distance from their star could be water-rich and habitable, astronomers say.

“We’ve also discovered planets completely unlike those in our solar system,” Borucki said Tuesday. “Some of those, in fact, might be worlds of water — actual water worlds. We’ve also found planets that were formed at the beginning of our galaxy, six-and-a-half billion years before the formation of our own star and the before the formation of the Earth. Imagine what life might be like on such planets.”

Scientists said Kepler’s observations yielded the discovery of between 2 and 12 near-Earth size planets in the habitable zone of their stars, according to NASA.

“Because of Kepler, we know that planets are an incredibly diverse set of objects, much more diverse than we observe in our own solar system,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division. “And because of Kepler, we know that solar systems come in a variety of configurations unlike our own.”

Borucki summed it up: “In a sense, our planetary system is quite atypical.”

Kepler was NASA’s first space mission dedicated to the search for planets around other stars.

Borucki, who retired from NASA in 2015 after 53-year career, started working on a planet-hunting telescope mission in 1983, nine years before astronomers even confirmed the discovery of the first exoplanet with ground-based observatories. His concept focused on using an ultra-sensitive instrument — using an array of light-detecting sensors called photometers coupled with a telescope — to monitor the brightness of stars and register faint dips in light when planets pass in front of their stars.

The technique is called the “transit method” for finding exoplanets, and it tells scientists about the size of each world, which can lead astronomers to infer whether the planet is a gaseous object or a rocky one.

Based at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California, Borucki and his team worked on the photometer technology in labs and on ground-based telescopes until NASA selected his Kepler proposal for full development in 2001.

Speaking with reporters Tuesday, Borucki likened Kepler’s technological achievement to “trying to detect a fly crawling across a car headlight when the car was 100 miles away. And the instrument must do it for 150,000 stars simultaneously.”

Built by Ball Aerospace, the Kepler spacecraft launched from Cape Canaveral on March 6, 2009, aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta 2 rocket. The launcher deployed Kepler into an Earth-trailing orbit around the sun, and the spacecraft has distanced itself from its home planet over its nearly decade-long mission, now located around 94 million miles (151 million kilometers) from Earth, according to Charlie Sobeck, Kepler’s project system engineer at Ames.

During Kepler’s four-year primary mission — from the observatory’s launch in March 2009 until early 2013 — the craft aimed its telescope at the same field of more than 150,000 stars in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra.

The 2013 failure of a second of four reaction wheels used to keep Kepler’s 3.1-foot (95-centimeter) telescope pointed prompted engineers to re-plan the mission. An extended observations campaign dubbed K2 began in 2014, using a combination of the two remaining reaction wheels, hydrazine fuel and solar pressure to maintain the telescope’s aim at a new star field every few months.

Kepler launched with 12 kilograms, or a little over 3 gallons, of hydrazine fuel feeding rocket thrusters to occasionally unload momentum from the observatory’s spinning gyro-like reaction wheels and offset solar pressure that could influence the spacecraft’s orientation.

“We knew when we launched that the spacecraft would ultimately be limited by its fuel load,” Sobeck said.

Sobeck said Kepler operated more than twice its original design life, and ground controllers first noticed signs of Kepler’s waning fuel supply in June as telemetry measurements showed pressures dropping in the spacecraft’s propulsion system.

“Because of fuel exhaustion, the Kepler spacecraft has reached the end of its service life,” Sobeck said. “While this may be a sad event, we are by no means unhappy with the performance of this marvelous machine.”

Sobeck said controllers will send the final command to Kepler in the coming weeks, ordering the spacecraft to disable its on-board fault protection software and turn off its transmitters.

Kepler collected its last science observations in September, ending a run that observed more than 530,000 stars and returned 678 gigabytes of data. Kepler’s discoveries also helped astronomers write nearly 3,000 scientific papers, a number that will continue to climb.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

“We found small potentially rocky planets around some of these bright stars, and those are now prime targets of current and future telescopes so we can move on to see what these planets are made of, how they are formed, and what their atmospheres be like,” said Jessie Dotson, Kepler project scientist at Ames.

“While we have ceased spacecraft operations, the science results from the Kepler data will continue for years to come,” she said.

A NASA spokesperson said the Kepler mission cost $692 million, including its development, launch and operations.

“I always felt like it was the little spacecraft that could,” Dotson said. “It always did what we asked of it, and sometimes more, and that’s a great thing to have from a spacecraft.”

“This marks the formal end of data collection, but not the end of data analysis thanks to NASA’s public archives,” tweeted Natalie Batalha, an astrophysicist and former Kepler project scientist. “I’m not sad. We did everything we wanted and more. Onward!”

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite launched in April to extend Kepler’s search across nearly the entire sky over a two-year prime mission. TESS will use the same “transit” search method as Kepler, but will focus on bright, nearby stars.

“NASA is handing off the mantle of planet-hunter from the Kepler space telescope to TESS — the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite — which is already in orbit and is discovering new exoplanets even as we speak,” Hertz said.

The long-delayed James Webb Space Telescope, now set for launch in 2021, will have the power to probe many of the planets discovered by Kepler and TESS and study the make-up of their atmospheres.

“The planets that TESS can find, we are hoping to put the next layer of information on those and determine what those planets are like as places,” said Padi Boyd, TESS project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. “It’s easy to measure the size of a planet — comparatively easy — but it’s much, much harder to be able to tell if that planet has an atmosphere, which is so important to life here on Earth. And if it does have an atmosphere, what does it contain? Does it contain water, which we believe is an essential building block for life?”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.